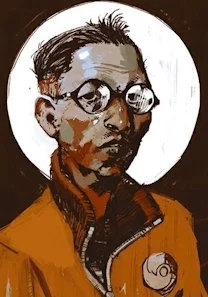

Kim Kitsuragi: Externalised Executive Function in Human Form

In Disco Elysium, Kim Kitsuragi is not just a partner character but a living model of executive function. This essay uses Kim as a case study to explain how planning, inhibition, working memory, and emotional regulation actually operate, what happens when they fail, and why we so often mistake psychological support for personality.

In most games, the companion character exists to provide banter, exposition, or combat utility. In Disco Elysium, Kim Kitsuragi exists to do something far more psychologically precise.

He thinks for you when you cannot.

Not metaphorically. Not narratively. Functionally.

Kim Kitsuragi is not merely a partner to the amnesiac detective. He is an externalised executive function, embodied as a person, embedded into the game’s mechanics, and quietly responsible for preventing total psychological collapse.

This makes Disco Elysium an unusually rich teaching tool. Where most media describe executive dysfunction, this game forces the player to experience life without executive control, and then hands them Kim as a prosthetic replacement.

What Executive Function Actually Is (And Why People Misunderstand It)

Executive function is often described lazily as “self-control” or “organisation”. This is misleading.

Psychologically, executive function refers to a cluster of higher-order cognitive processes that allow an individual to:

Plan and sequence actions

Inhibit inappropriate impulses

Hold and manipulate information in working memory

Shift flexibly between tasks or perspectives

Monitor behaviour and correct errors

Regulate emotion in service of goals

In other words, executive function is not about intelligence or morality. It is about coordination.

When executive function is intact, behaviour appears coherent. When it is impaired, even simple tasks become overwhelming, not because the person lacks insight, but because the system that organises insight into action is compromised.

This distinction matters, because Disco Elysium’s protagonist is not stupid, ignorant, or unaware. He is flooded with information, emotion, memory fragments, and impulses, but lacks the capacity to prioritise, inhibit, and integrate them.

That is executive dysfunction.

The Detective: A Mind Without a Conductor

The player-character in Disco Elysium is not a blank slate. He is a fragmented mind.

His internal monologue is a cacophony of competing drives: fear, bravado, despair, ideology, self-disgust, hope. Skills speak over one another. Thoughts interrupt. Emotions escalate without warning.

Crucially, the game does not present this as inner conflict that will be resolved through growth. It presents it as baseline functioning.

This mirrors real-world executive dysfunction seen in:

Severe substance use disorders

Traumatic brain injury

ADHD

Mood disorders

Chronic stress and burnout

In these states, insight often survives. Organisation does not.

The detective can understand consequences, values, and goals. What he cannot do reliably is hold them steady long enough to act on them.

Enter Kim Kitsuragi.

Kim as Executive Function, Not Moral Compass

It is tempting to describe Kim as the “voice of reason” or the “moral centre” of the game. Psychologically, this misses the point.

Kim does not primarily tell you what is right. He tells you what is relevant.

He:

Redirects attention back to the task when the detective spirals

Provides temporal structure (“We should proceed”, “That can wait”)

Reality-checks delusions without humiliation

Interrupts impulsive or performative behaviour before it escalates

Translates abstract chaos into concrete next steps

These are classic executive processes.

Notice how rarely Kim moralises. Even when he disapproves, his language is restrained, procedural, and outcome-focused. He is not there to shape your values. He is there to keep the cognitive system operational.

This is why Kim feels grounding rather than controlling. He is not imposing direction. He is supplying structure.

Working Memory: Kim as the Mind That Holds the Thread

Working memory is the ability to hold information in the mind long enough to use it. It is one of the first casualties of executive dysfunction.

The detective struggles with this constantly. He forgets names, contexts, and intentions mid-conversation. Threads dissolve. Associations overwhelm sequence.

Kim compensates.

He remembers case details. He recalls earlier statements. He gently reintroduces context when the detective drifts. When the player forgets why something matters, Kim often remembers for them.

This is not narrative convenience. It is functional substitution.

In real life, people with impaired executive function often rely on external supports: planners, reminders, structured routines, or other people. Kim is this personified.

Inhibitory Control: Stopping the Spiral Before It Becomes Behaviour

One of the most psychologically accurate aspects of Kim’s role is how he handles inhibition.

He does not shame impulsivity. He does not catastrophise it. He simply interrupts it early.

When the detective is about to:

Grandstand ideologically

Perform self-destructive theatrics

Escalate conflict unnecessarily

Lean into humiliation or cruelty

Kim intervenes with minimal affect.

This mirrors effective real-world executive support. Inhibition works best when it is calm, early, and non-punitive. Once emotional arousal peaks, executive control is already lost.

Kim functions as a pre-emptive brake, not a post-hoc judge.

Emotional Regulation: Co-Regulation, Not Suppression

Executive function is inseparable from emotion regulation. Not the absence of emotion, but the ability to modulate it in service of goals.

Kim does not suppress the detective’s emotions. He does not tell him to “calm down” or “be rational”. Instead, he helps contain emotional intensity long enough for action to remain possible.

This is co-regulation.

In psychology, co-regulation refers to the process by which one nervous system stabilises another through presence, predictability, and responsiveness. It is foundational in early development and remains crucial in adulthood under stress.

Kim provides this continuously:

Through tone

Through pacing

Through predictable responses

Through refusal to escalate

He does not fix the detective’s emotions. He keeps them from hijacking behaviour.

Task Switching and Cognitive Flexibility

Another executive function Kim quietly supplies is task switching.

The detective is prone to fixation. He latches onto ideas, symbols, theories, or emotional states and struggles to disengage. Kim reorients him toward the immediate demands of the case.

“Later.”

“That’s not relevant right now.”

“We should move on.”

These moments are not dismissive. They are scaffolding.

In real-world executive dysfunction, difficulty shifting tasks is common. Individuals may perseverate on thoughts or activities long after they cease to be useful. External cues are often necessary to prompt transition.

Kim is that cue.

Why Kim Rarely Breaks

One of the most telling design choices in Disco Elysium is that Kim almost never becomes dysregulated himself.

This is not because he is immune to stress. It is because the system cannot afford for him to fail.

If Kim collapsed emotionally, the game’s experiment would collapse with him. The player would be left alone inside an uncontained mind. That would be accurate, but unplayable.

So Kim remains intact.

This mirrors real-world dynamics in caregiving and professional support roles. Teachers, nurses, therapists, partners of people with chronic dysregulation often maintain composure not because they are unaffected, but because someone has to hold the line.

The cost is simply not shown.

The Ethical Question the Game Quietly Asks

Disco Elysium never explicitly asks whether it is fair for Kim to carry this burden.

But it lets the player feel the dependence.

As the game progresses, many players notice a dependence on Kim, often elevating him beyond a mere videogame companion, but what this hides is a subtle anxiety: What would happen if Kim weren’t here? And that question is the lesson.

Executive function is invisible when it works. When it is gone, everything else becomes harder.

Kim makes executive function visible by embodying it.

He is not a model of psychological health. He is a model of psychological support.

And crucially, he demonstrates that support does not look like advice, control, or correction. It looks like staying present, organised, and calm when someone else cannot.

Simply Put

The protagonist of Disco Elysium is a study in cognitive collapse. Substance dependence, identity fragmentation, mood instability, and self-loathing are not narrative colour. They are gameplay systems.

Kim Kitsuragi’s role is not to repair this damage. It is to contain it.

He reality-checks hallucinations, redirects impulsive decisions, and supplies structure when the detective drifts toward nihilism or self-destruction. He does so quietly, predictably, and without spectacle. His regulation is not heroic; it is procedural. And it is precisely this lack of drama that allows the player to explore dysfunction without the experience becoming unplayable.

Psychologically, Kim occupies a role familiar far beyond fiction: the partner, carer, or colleague who manages tone, pace, and consequence for someone whose internal regulation is failing. He prevents collapse without erasing responsibility, and support without absolution.

Crucially, Kim rarely asks for care in return.

The game acknowledges his interiority, but never requires the player to tend to it. His emotional labour is framed as competence rather than cost, as professionalism rather than effort. Stability is treated as essence, not expenditure.

This is not an oversight. It is structural.

If Kim were allowed to meaningfully break, the system would fail. The player would be left alone inside an uncontained mind, and the experiment Disco Elysium is running would end.

Kim must remain intact so the player can safely fall apart.

The Kim Kitsuragi Effect: What We Have Learned About Executive Function

By observing the partnership between the detective and Kim Kitsuragi, we can draw a clearer, more compassionate map of the mind’s executive “command centre”.

If the protagonist is the engine — powerful, volatile, and prone to catastrophic overheating — then Kim is the cooling system and the steering rack. He does not supply power. He supplies control.

Through this lens, four essential truths about executive function come into focus.

1. Executive Function Is a Cognitive Battery, Not a Personality Trait

Disco Elysium repeatedly demonstrates that executive function is finite.

When the detective is flooded by intrusive thoughts, emotional distress, or substance withdrawal, his ability to plan, inhibit impulses, or make coherent decisions collapses. Not gradually. Immediately.

This is not a failure of character. It is a failure of capacity.

The lesson:

What we often label as “willpower” is a biological resource. When the brain’s frontal systems are taxed by trauma, stress, or neurodivergence, organisation and self-control do not disappear because a person “chooses badly”. They disappear because the system is out of charge.

Kim’s calm presence does not magically improve the detective’s morals. It restores just enough battery for the system to function.

2. Inhibition Is the First Line of Defence

Executive function is not primarily about doing more. It is about stopping.

Some of Kim’s most important interventions are minimal: a pause, a raised eyebrow, a quiet redirection when the detective is about to grandstand, spiral, or self-sabotage. He does not argue every impulse. He intercepts it before it becomes behaviour.

The lesson:

Healthy executive function acts as a gatekeeper. Without it, every thought becomes speech and every urge becomes action. Kim teaches us that the ability to pause — even briefly — is the foundation of rational behaviour.

Self-control begins not with discipline, but with delay.

3. Scaffolding Is a Legitimate Response to Cognitive Disability

Kim fundamentally reframes what “help” looks like.

He does not carry the detective. He does not take over. He provides structure: reminders, pacing, focus, and external order. This is known clinically as environmental scaffolding.

The detective still solves the case. Kim simply makes it possible.

The lesson:

For people with ADHD, autism, traumatic brain injury, or severe stress, “trying harder” is rarely the solution. The solution is often external: routines, lists, predictable environments, or supportive others who temporarily supply what the brain cannot.

Support is not weakness. It is engineering.

4. Regulation Is a Shared Process (Co-Regulation)

Perhaps the most quietly radical lesson of Disco Elysium is that executive function does not have to live entirely inside one skull.

Kim’s steady presence demonstrates co-regulation in action. His predictability, calm tone, and emotional containment actively stabilise the detective’s nervous system. This is not symbolic. It is physiological.

The lesson:

Human nervous systems are open loops. We regulate one another constantly. When one person is dysregulated, a calm, reliable partner can quite literally slow heart rate, reduce cognitive noise, and restore clarity.

Independence is not the absence of support. It is the ability to use it.

Kim Kitsuragi reminds us that executive function is the invisible glue of the self. We rarely notice it when it works, and we blame ourselves when it fails.

But Disco Elysium offers a gentler truth.

Even the most fragmented mind can function, decide, and persist — not by becoming stronger, but by being supported in the right way, at the right time, by someone willing to hold the structure steady.

Sometimes, solving the case is less about fixing the engine, and more about having someone who knows how to steer while it cools.

References

ZA/UM. (2019). Disco Elysium [Video game]. London, UK: ZA/UM.