A Mind Unraveling: Slay the Princess as a Metaphorical Narrative of Dementia

Slay the Princess takes on new depth when read as a metaphor for dementia. Its loops echoing episodic memory loss, its shifting relationships mirroring fractured identity, and its collapsing world reflecting cognitive decline. This interpretation reframes the game as a haunting allegory of a mind slowly unravelling.

Slay the Princess is widely interpreted through lenses such as Jungian psychology, metafiction, trauma, and identity fragmentation. Yet one reading remains surprisingly overlooked despite its strong thematic fit: the game can be read as a metaphor for dementia and the progressive dissolution of memory, selfhood, and relational identity. When approached through this framework, the game’s structural loops, its shifting characters, and the Hero’s recurring amnesia form a coherent symbolic model of cognitive decline. This interpretation provides a new and emotionally powerful way to understand the game’s recursive narrative and psychological motifs, revealing Slay the Princess not only as a meditation on identity and morality but also as a deeply resonant allegory for neurodegeneration.

Note: This reading isn’t a claim about the creators’ intentions, but an interpretive lens that highlights themes the game’s structure naturally appears to support.

The Loop Structure as Cognitive Reset

The defining feature of dementia is the gradual breakdown of memory formation and retrieval. People experiencing dementia often wake into moments of disorientation, unable to anchor themselves in time or recall previous events. They ask the same questions repeatedly. They try to reestablish relationships they no longer remember. Their world becomes fragmented and cyclical.

The loops in Slay the Princess mirror this pattern with striking fidelity. Each cycle begins with the Hero awakening as if from a restless sleep. He retains no explicit memory of what occurred before, yet he is compelled to walk the path again and repeat familiar patterns. The repetition is not a quest structure borrowed from gaming conventions. It operates more like the lived experience of cognitive reset. The Hero’s confusion upon starting each loop resembles the disorientation often observed during dementia-related “sundowning” episodes or waking periods marked by impaired orientation.

Crucially, the loops feel both new and familiar. The Hero recognizes nothing, but the environment has the uncanny quality of déjà vu. This blend of novelty and familiarity is central to dementia phenomenology. The player experiences the same disjunction that characterizes memory loss: a world that feels known yet unreachable.

Implicit Memory Surviving Explicit Forgetting

Dementia does not eliminate memory evenly. It typically erodes episodic memory first: memories of events, facts, and sequences of experience. Emotional memory, procedural memory, and instinctual reactions often survive longer, creating a split between what the person knows and what the person feels.

The Hero embodies this divide. Although he cannot recall previous loops, he behaves as if some emotional residue remains. He may fear the Princess without knowing why. He may distrust the Narrator despite lacking evidence. He may feel drawn to protect or comfort the Princess even though he has no memory of past intimacy. These emotional instincts contradict the literal amnesia and reveal the survival of nonconscious memory systems.

The persistence of the internal Voices strengthens this reading. Voices that develop in one loop reappear in later loops, functioning like procedural memory or internalized emotional patterns. They are not factual recollections. They are habits of mind. Their survival across cycles mirrors the neurological reality that personality traits, emotional biases, and conditioned responses often persist even when explicit memories disappear.

This creates a psychologically realistic portrait of fragmented retention. The Hero’s “forgetting” mimics the cognitive architecture of dementia rather than the total wipes typical of time loops in fiction.

The Princess as the Keeper of Lost Memory

One of the most compelling parallels between the game and dementia is the Princess’s role as the consistent holder of memory. She remembers past loops. She remembers who the Hero once was, how he treated her, how he feared her, or how he loved her. Her forms change in response to these remembered experiences, even when he cannot access them.

This dynamic mirrors the emotional asymmetry common in dementia relationships, particularly between caregivers and patients. Loved ones often carry the entire burden of shared history, while the person with dementia may no longer recognize them. The emotional weight of memory becomes one-sided. The Princess’s shifting demeanor reflects how personal relationships can transform in the face of memory loss. To the Hero, she is sometimes a stranger, sometimes a threat, and sometimes a comfort. To the Princess, he remains the same person whose actions have shaped her, even if he no longer remembers acting.

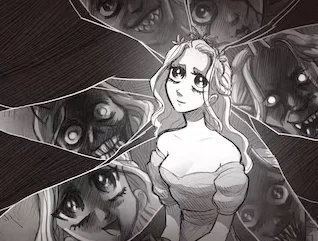

When the Princess becomes monstrous, fragmented, or afraid, it reflects the emotional toll of holding memories that the other person has lost. When she becomes gentle or melancholic, it evokes the longing many caregivers feel for the earlier versions of their loved ones. Her transformations become metaphors for the shifting emotional landscapes of relationships altered by memory decay.

The Narrator as the Executive Function in Decline

The Narrator occupies a role that closely resembles the cognitive control system in the human mind. He attempts to impose order on chaos, maintain a coherent story, and guide the Hero toward a consistent goal. As the loops progress, the Narrator becomes increasingly agitated and unstable. His logic frays. His certainty collapses. He attempts to rewrite or override reality to preserve a sense of purpose.

This matches the psychological deterioration associated with dementia, particularly the decline of executive functioning. As dementia progresses, the mind struggles to maintain continuity, suppress irrelevant information, and construct stable narratives about the world. Confabulation, emotional volatility, and narrative inconsistency emerge. The Narrator’s degeneration reflects this internal struggle for cognitive stability.

He remembers more than the Hero but less than the Princess, placing him in the symbolic position of a mind losing the ability to coordinate between internal systems and lived experience. His increasing desperation can be interpreted as the last effort of a fading cognitive structure trying to preserve coherence in the face of inevitable breakdown.

The Constricted World as a Shrinking Cognitive Environment

As dementia progresses, a person’s cognitive world contracts dramatically. Complex environments become confusing and frightening. Familiar places become labyrinths. Eventually, the person’s world shrinks to a room, a chair, a bed, a caregiver’s face. The once-vast cognitive landscape narrows to a few repeating elements.

The world of Slay the Princess exhibits this same contraction. The Hero’s universe consists of a path, a cabin, a basement, and the Princess. Almost nothing exists outside this closed loop. The world offers no alternative spaces, no opportunities for exploration, and no stable outside context. The recursive design creates an experience that mimics the shrinking scope of cognitive life during dementia. Everything is stripped down to essential emotional symbols.

The path is orientation.

The cabin is the familiar home that has become strange.

The basement is the site of fear and uncertainty.

The Princess is the central relational figure.

The Narrator is the thinning cognitive scaffolding.

The entire game becomes a symbolic microcosm of a mind in decline.

Identity Dissolution and the Final Godhood Ending

Late-stage dementia is marked by the dissolution of personal identity. The sense of self becomes fragmented and archetypal. Language breaks down into emotional impressions. The world loses its narrative shape. What remains are basic emotional impulses: fear, comfort, stasis, change. The final endings of Slay the Princess, which elevate the Hero and the Princess to cosmic archetypes, resemble this dissolution. The loss of personal identity gives way to symbolic representation. The Hero becomes the Long Quiet. The Princess becomes the Shifting Mound. They cease to be people and become forces.

Viewed through a dementia lens, these endings do not represent divine ascension. They represent the final unraveling of self. The personal story collapses and only emotional symbols remain. The world becomes mythic not because it expands, but because the mind has collapsed into pure archetype.

| Game Element | Psychological Concept |

|---|---|

| Loops | Episodic memory loss |

| Residual emotions | Implicit memory |

| Voices | Procedural / emotional retention |

| Princess | Caregiver / memory holder |

| Narrator | Executive function |

| World contraction | Cognitive narrowing |

| Final archetypes | Identity dissolution |

Simply Put

Interpreting Slay the Princess as a metaphor for dementia produces a coherent, emotionally resonant reading that aligns with the game’s narrative structure, psychological mechanisms, and symbolic architecture. The looping amnesia reflects episodic memory loss. The persistence of emotional instincts mirrors implicit memory. The Princess functions as the repository of shared history. The Narrator embodies the failing attempt to maintain coherence. The shrinking world mirrors cognitive reduction. The final archetypal dissolution parallels the late stages of identity breakdown.

This interpretation does not replace existing frameworks. It complements them by unveiling a new dimension of the game’s narrative complexity. Slay the Princess becomes not only a story about moral ambiguity or psychological fragmentation, but also a haunting allegory for a mind losing its history, its relationships, and ultimately itself.

References

Baddeley, A., Eysenck, M. W., & Anderson, M. C. (2020). Memory (3rd ed.). Psychology Press.

Hodges, J. R. (2017). Cognitive assessment for clinicians (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Open University Press.

Slay the Princess. (2024). Retrieved November 19, 2025, from https://www.slaytheprincess.com/

Explore how Slay the Princess subverts the stereotypical princess trope, drawing on psychological theories and peer-reviewed sources to analyse its impact on perceptions of gender and agency.