Memory, Forgetting, and Identity Reconstruction Across Loops in Slay the Princess

The looping structure of Slay the Princess is one of its most distinctive narrative features, yet it is rarely examined through the lens of memory and psychological continuity. Most interpretations focus on moral choice, identity fragmentation, or archetypal symbolism. Far fewer analysts have explored the role of forgetting, the survival of unconscious residues, and the reconstruction of identity from incomplete psychological material. This is surprising because the game uses memory in a highly deliberate and symbolically rich way. Forgetting in Slay the Princess is not merely a reset between narrative branches. It functions as a narrative technology that shapes identity, emotional inheritance, and the logic of the world.

The Hero begins each loop without conscious memory of previous events. Despite this apparent erasure, traces remain. Instincts, fears, internal voices, and subtle attitudes persist in ways that are inconsistent with literal amnesia. The Hero forgets what happened, but the psyche remembers. The Princess also remembers. The Narrator remembers. The world itself appears to remember. This creates a layered system of memory in which forgetting is not the absence of knowledge but the transformation of experience into unconscious form.

Understanding this system reveals a deeper psychological and symbolic reading of the game. The loops behave like traumatic reenactments in which the individual consciously forgets past harm yet remains shaped by its emotional residue. Identity is repeatedly reconstructed through fragments that survive the erasure. The outcome is a compelling metaphor for trauma, recurrence, and the nonlinear formation of the self.

Memory Erosion as Narrative Technology

The most striking feature of the game's memory system is the selective erosion that occurs between loops. The Hero does not simply forget everything. Instead, the game allows certain impressions to pass through while stripping away narrative context. This erasure functions more like dissociative amnesia than a mechanical reset. Dissociative amnesia often involves the loss of explicit memory while emotional learning and implicit patterns remain intact. Survivors of trauma may forget specific events but still react to triggers or recreate patterns without understanding their origin.

In Slay the Princess, the Hero frequently enters a new loop with instinctive reactions that have no conscious justification. A Hero who has struck the Princess in a previous loop may develop immediate guilt, fear, or defensiveness in the next. A Hero who trusted the Princess may feel protective or drawn to her even if he cannot articulate why. These emotional residues suggest that memory erodes unevenly. What disappears is the explicit recollection. What remains is the emotional core of previous experience.

This mechanism structures the entire narrative. The loop is not a blank slate. It is a cleaned slate that still holds faint impressions of its prior inscriptions. By using amnesia in this way, the game invites the player to notice what survives forgetting and to question why certain psychological traces persist while others vanish completely.

Unconscious Continuity Across Loops

The persistence of memory in unconscious form is one of the most important clues to the psychological architecture of Slay the Princess. The Hero’s internal voices are the clearest representation of this continuity. Voices that appeared due to specific choices in earlier loops may reappear in later ones even when the Hero no longer remembers the events that created them. The existence of these voices across loops suggests that they are not tied to conscious recollection. They emerge from behavioral patterns and emotional tendencies, not explicit memories.

This mirrors concepts from contemporary psychology in which implicit memory persists even when explicit memory fails. For example, a person who forgets learning a skill may still demonstrate proficiency. Someone who cannot recall a traumatic event may still respond with fear or avoidance to related stimuli. The game uses this dynamic to generate a sense of psychological layering. Each loop constructs new aspects of identity on top of residual emotional structures from the previous cycle.

This dynamic makes the Hero's psyche feel organic. Identity does not reset, nor does it advance linearly. It mutates in response to the selective survival of unconscious material. The Hero becomes a composite of forgotten actions that continue to shape future behavior.

The Princess as the Archive of Forgotten Histories

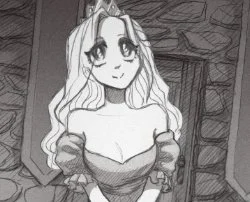

While the Hero forgets, the Princess often remembers. She carries forward knowledge of prior loops in a way that the Hero cannot. Her shifting forms reflect the emotional tone and choices of earlier loops. If she was approached with violence, she may become monstrous or defensive. If she was approached with empathy, she may become more vulnerable or introspective. These changes persist between loops even when the Hero has no recollection of the decisions that shaped her.

This creates a powerful metaphor. The Princess becomes the living archive of forgotten acts. She is the embodiment of the Hero’s unconscious memory, solidified into narrative form. What the Hero represses or forgets becomes externalized in her reactions, her transformations, and her expectations of him. She is not simply a character who reacts to the player. She is the accumulation of all the Hero’s forgotten selves.

This dynamic strongly resembles relationships in which one person forgets harmful behavior while the other carries the emotional consequences. In trauma studies, this is sometimes described as the imbalance between perpetrator amnesia and victim remembrance. The game transforms this psychological pattern into a narrative cycle.

The Narrator and the Logic of Memory

The Narrator further complicates the memory system by acting as a partial guardian of knowledge. He remembers more than the Hero but less than the Princess. His recollections are biased, incomplete, and shaped by fear. As loops progress, he becomes increasingly desperate, which suggests that he experiences continuity that the Hero does not. His anxiety is cumulative.

Psychologically, this positions the Narrator as a representation of what might be called selective cognitive control. He attempts to impose a narrative, maintain order, and restrict the Hero’s interpretation of events. However, he cannot fully suppress the emotional consequences of previous loops. He is the psyche attempting to control memory while failing to prevent the return of the repressed. His fear grows even as the Hero’s memory resets. This creates an internal conflict between the conscious desire to maintain a coherent story and the unconscious tendency for unresolved material to resurface.

Identity Reconstruction Through Fragmentation

Because the Hero enters each loop with partial memory loss, identity must be reconstructed from the fragments that survive. These fragments include internal voices, emotional tendencies, and embodied habits. The Hero interprets new information through the lens of these residues. If a previous loop reinforced suspicion, the Hero may distrust the Princess even without knowing why. If a previous loop emphasized tenderness, the Hero may feel protective or conflicted.

This reconstruction process mirrors how identity forms in real psychological development. People build their sense of self not from a continuous, perfectly coherent narrative, but from fragments of memory that they reinterpret, compensate for, or supplement. Identity is not the product of perfect recall. It is the product of what persists emotionally and what is reconstructed from incomplete information.

In this sense, the loop structure becomes a model for how the self is continually reauthored. Forgetting is not a loss of identity. It is part of the mechanism through which identity is rewritten.

Trauma, Repetition, and Symbolic Recurrence

The loops in Slay the Princess function much like traumatic repetition. Freud described repetition compulsion as the tendency to reexperience unresolved conflicts in symbolic form. The game enacts this principle with remarkable clarity. The cabin, the Princess, and the Narrator become recurring symbols. The Hero repeatedly confronts the same conflict with slightly altered conditions. The inability to remember past cycles forces the Hero to reenact them without conscious understanding, which is one of the defining features of trauma.

At the same time, each loop provides an opportunity for change. The emotional residues that survive each reset create small shifts in identity that accumulate over time. This aligns with contemporary trauma therapy, which often involves revisiting traumatic material under new conditions to create reinterpretation and healing. The game’s structure uses memory erosion to simulate this gradual process of working through.

Amnesia as Design

Forgetting is not presented as a flaw or limitation of the narrative. It is a deliberate mechanism that enables the game to explore the formation of identity through recurrence. Amnesia allows each loop to function as a fresh encounter while still carrying emotional continuity. This creates a dynamic in which identity is fluid but not arbitrary. The Hero evolves not through accumulated knowledge but through accumulated affect.

In narrative terms, this makes Slay the Princess unusually sophisticated. The game models the nonlinearity of memory, the layers of the unconscious, and the cyclical nature of unresolved conflict. Memory becomes the foundation of a narrative psychology that operates beneath the level of conscious recall.

Simply Put

Memory in Slay the Princess is neither stable nor absent. It functions as a recursive, emotionally driven system that shapes identity across loops. The Hero forgets the events of previous cycles, but unconscious residues persist. These residues influence reactions, shape internal voices, and guide the reconstruction of personality. The Princess becomes a repository of forgotten acts, while the Narrator represents the faltering attempt to control the narrative of memory. Together, they illustrate a model of the self in which identity is continually rebuilt from fragments that survive the erosion of explicit memory.

The game’s use of amnesia transforms its loop structure into a symbolic exploration of trauma, recurrence, and the persistence of emotional truth. By examining what is forgotten and what remains, Slay the Princess provides a compelling framework for understanding how memory shapes the self even when recollection fails.

References

Janet, P. (1925). Psychological healing: A historical and clinical study. George Allen & Unwin.

Schacter, D. L. (1996). Searching for memory: The brain, the mind, and the past. Basic Books.

Schacter, D. L., & Tulving, E. (Eds.). (1994). Memory systems 1994. MIT Press.

Slay the Princess. (2024). Retrieved November 19, 2025, from https://www.slaytheprincess.com/