How to Justify Your Sampling Method in a Psychology Assignment/Report

1. Introduction: Why Sampling Method Justification Matters

In the realm of psychological research, the selection of your participants is far from an arbitrary step; it is a fundamental design decision that profoundly impacts the validity, reliability, and generalisability of your findings. When you embark on a psychology assignment, lab report, or dissertation, you'll inevitably encounter the task of outlining your sampling method. However, merely stating what method you used is insufficient. Markers, supervisors, and peer reviewers expect to see a robust justification for your choice – an explanation of why this particular method was the most appropriate for your specific research question and design.

Justifying your sampling method means articulating the rationale behind your participant recruitment strategy. It involves demonstrating that you have critically considered how your chosen method aligns with your research aims, acknowledges potential biases, and addresses practical constraints. Markers specifically look for this justification as it signals a deep understanding of research methodology, an awareness of the inherent limitations of any study, and a commitment to rigorous scientific practice.

A common pitfall for students is to justify their sampling method with a simple, pragmatic statement like, "We used convenience sampling because it was easy." While ease of access might be a contributing factor, it's never a sufficient justification on its own. Such a statement suggests a lack of critical thought about the methodological implications of the choice. A strong justification, conversely, shows that you've weighed the pros and cons, considered alternative approaches, and made an informed decision based on the specific context of your study.

Ultimately, whether you're planning a lab report, dissertation, or ethics proposal, your sampling method isn't just a line you fill in — it's a design decision that tells your reader how your results were shaped. Choosing and justifying your sampling approach shows you're thinking critically about bias, generalisability, and feasibility.

2. Overview: What Counts as a Sampling Method in Psychology

Before we delve into justification, it's crucial to understand the different types of sampling methods commonly employed in psychological research. These methods generally fall into two broad categories: probability sampling and non-probability sampling. The distinction lies in whether every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected for the study.

Probability Sampling: In probability sampling, every individual in the target population has a known, non-zero chance of being selected. This allows for the calculation of sampling error and makes it possible to generalise findings from the sample to the broader population with a higher degree of confidence.

Simple Random Sampling: Every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. This is often achieved by randomly drawing names from a list or using a random number generator.

Best For: Studies where generalisability to a well-defined population is paramount, and a complete list of the population is available.

Limitations: Can be time-consuming and difficult to achieve with large populations; may not be feasible if a complete list of the population is unavailable.

Stratified Random Sampling: The population is divided into subgroups (strata) based on relevant characteristics (e.g., age, gender, socioeconomic status), and then a random sample is drawn from each stratum. This ensures representation of key subgroups.

Best For: Research where it's important to ensure specific subgroups are proportionately represented in the sample, especially when comparing groups.

Limitations: Requires prior knowledge of population characteristics and the ability to divide the population into strata; can be more complex than simple random sampling.

Cluster Sampling: The population is divided into clusters (e.g., schools, hospitals, neighbourhoods), and then a random sample of clusters is selected. All individuals within the selected clusters are then included in the sample.

Best For: Large-scale studies where it's impractical to sample individuals directly, especially when populations are geographically dispersed.

Limitations: Increased sampling error compared to simple random or stratified random sampling; individuals within clusters may be more homogeneous, leading to less diverse samples.

Systematic Sampling: Every nth individual is selected from a list of the population, after a random starting point is chosen.

Best For: When a complete list of the population is available and a quick, efficient sampling method is desired.

Limitations: If the list has a hidden pattern, it could introduce bias; requires a complete and ordered list.

Non-Probability Sampling: In non-probability sampling, individuals are selected based on non-random criteria, such as convenience or specific characteristics. This approach does not guarantee that every member of the population has an equal chance of selection, which limits the ability to generalise findings to the broader population.

Convenience Sampling: Participants are selected based on their easy accessibility and willingness to participate.

Best For: Pilot studies, preliminary research, and studies with limited resources where rapid data collection is needed.

Limitations: High risk of sampling bias; findings may not be generalisable to the broader population; often over-represents certain demographics.

Snowball Sampling: Participants are recruited through referrals from existing participants. This method is particularly useful for reaching hard-to-access populations.

Best For: Research on hidden or difficult-to-reach populations (e.g., individuals with rare conditions, specific subcultures, illegal activities).

Limitations: High risk of sampling bias as participants are not independent; generalisability is severely limited; can be slow.

Quota Sampling: Similar to stratified sampling, the researcher identifies specific subgroups and sets quotas for the number of participants needed from each subgroup. However, participants are then recruited using non-random methods (e.g., convenience sampling) until the quotas are met.

Best For: When it's important to have representation from specific subgroups but probability sampling is not feasible or necessary.

Limitations: Selection within quotas is non-random, leading to potential bias; generalisability is limited compared to stratified random sampling.

Purposive (Judgement) Sampling: The researcher deliberately selects participants based on their expertise, specific characteristics, or knowledge relevant to the research question.

Best For: Qualitative research, expert opinion studies, or when specific insights from particular individuals are required.

Limitations: Highly subjective and prone to researcher bias; findings are not generalisable to the broader population.

Here's a mini-table to summarise:

| Sampling Method | Description | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability Sampling | |||

| Simple Random | Every individual has an equal chance of selection. | Maximising generalisability; when a complete population list is available. | Time-consuming; impractical for large populations; requires complete list. |

| Stratified Random | Population divided into subgroups (strata), then random samples drawn from each. | Ensuring proportional representation of key subgroups; comparing between groups. | Requires prior population knowledge; more complex. |

| Cluster | Population divided into clusters; random clusters selected, all individuals within clusters participate. | Large-scale studies, geographically dispersed populations, when individual sampling is impractical. | Increased sampling error; individuals within clusters may be homogeneous. |

| Systematic | Every nth individual selected from a list after a random start. | Efficient for large lists; when a complete and ordered list is available. | Potential for bias if hidden patterns exist in the list. |

| Non-Probability Sampling | |||

| Convenience | Participants selected based on ease of access and availability. | Pilot studies, preliminary research, resource-limited studies, rapid data collection. | High risk of bias; limited generalisability; over-represents certain demographics. |

| Snowball | Participants recruit other participants from their network. | Reaching hidden, niche, or hard-to-access populations. | High risk of bias; limited generalisability; slow. |

| Quota | Non-random selection of participants to meet predetermined quotas for specific subgroups. | Ensuring representation of subgroups when probability sampling isn't feasible, or for quick comparisons across groups. | Selection within quotas is non-random, leading to bias; limited generalisability. |

| Purposive (Judgement) | Researcher deliberately selects participants based on their expertise or specific characteristics. | Qualitative research, expert opinion studies, when specific insights from particular individuals are required. | Highly subjective, prone to researcher bias; findings not generalisable. |

3. What Markers and Supervisors Want to See in Justifications

A strong justification goes beyond merely naming your sampling method. Markers and supervisors are looking for evidence of critical thinking and a comprehensive understanding of your research design. They want to see that you've considered the methodological implications of your choices and how they align with your overall study. Here's what makes a good justification:

Connection to Research Aims: The most crucial aspect is demonstrating how your sampling method directly supports your research question and objectives. If your aim is to generalise findings to a large population, you'll need a different approach than if you're exploring a specific phenomenon in depth within a small, unique group.

Ethical Considerations: Your justification should reflect an awareness of ethical principles. For instance, if you're studying a vulnerable population, your sampling method might prioritise their safety and welfare over pure randomisation. How did you ensure informed consent and minimise harm?

Real-World Constraints: Acknowledge practical limitations such as time, budget, and accessibility of participants. It's perfectly acceptable to admit that these constraints influenced your choice, but you must then explain how you mitigated potential negative impacts.

Clear Awareness of Bias: No sampling method is perfect, and all have potential biases. A good justification explicitly identifies the biases inherent in your chosen method and, ideally, outlines how you attempted to minimise or account for them in your analysis or discussion. This demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of methodological rigour.

Let's compare some vague versus strong examples to illustrate these points:

❌ Vague Justification: "We used convenience sampling because it was available."

Why it's weak: This statement provides no insight into the researcher's thought process, the study's aims, or an understanding of the method's limitations. It implies a lack of methodological consideration.

✅ Strong Justification: "Due to the study’s focus on undergraduate sleep patterns and the feasibility of access within a university setting, a convenience sample of Year 2 psychology students was selected from a participating university. This approach allowed for rapid recruitment and data collection, which was essential given the project's tight timeline. While acknowledging potential limitations in generalisability to the broader student population or individuals outside of this specific demographic, the sample's homogeneity regarding academic pressures and age range was considered appropriate for exploring preliminary relationships between study habits and sleep quality within this specific context. Future research could aim for a more diverse sample through stratified sampling."

Why it's strong: This justification explicitly links the sampling method to the study's focus (undergraduate sleep patterns), addresses feasibility (rapid recruitment, tight timeline), acknowledges the limitation of generalisability, and even suggests how this limitation might be addressed in future research. It shows critical thinking about the trade-offs involved.

❌ Vague Justification: "Participants were randomly selected."

Why it's weak: This is too brief and lacks detail. How were they randomly selected? From what population? What steps were taken to ensure true randomness?

✅ Strong Justification: "To investigate the efficacy of a new memory training programme, a simple random sample of 100 participants was drawn from a comprehensive list of registered residents aged 65-75 in a specific urban area. This method was chosen to maximise the external validity of the findings, ensuring that each individual within the target demographic had an equal probability of inclusion, thereby reducing selection bias and supporting generalisability of the training programme's effects to the wider older adult population in this region."

Why it's strong: This justification specifies the type of random sampling, the target population, the rationale for choosing it (maximising external validity, reducing bias), and the intended outcome (generalisability).

4. How to Choose the Right Sampling Method (with Examples)

Choosing the right sampling method is not a one-size-fits-all decision; it's a strategic choice dictated by several factors inherent to your research. Consider the following:

Study Aim: What is the primary objective of your research? Are you aiming to describe a population, establish cause-and-effect relationships, explore a phenomenon in depth, or compare different groups?

Participant Characteristics: Who are you trying to study? Is it a specific, hard-to-reach group, or a broad, accessible population?

Resource Constraints: What are your limitations in terms of time, budget, and access to participants?

Ethics: Are there any ethical considerations that might influence your ability to recruit participants (e.g., vulnerability, privacy)?

Let's explore some scenario-based breakdowns:

Scenario 1: Studying attitudes toward therapy among LGBTQ+ youth

Study Aim: To understand the nuanced attitudes, barriers, and facilitators to seeking therapy among a specific, potentially vulnerable, and often hidden population. Generalisability to the broader youth population is less critical than gaining rich, in-depth insights from the target group.

Participant Characteristics: LGBTQ+ youth may be hesitant to disclose their identity, making direct random sampling difficult.

Resource Constraints: Limited access to comprehensive lists of LGBTQ+ youth.

Ethics: Ensuring safety, anonymity, and trust is paramount.

Possible Sampling Method: Snowball Sampling or Purposive Sampling.

Justification Rationale: "Given the sensitive nature of the topic and the potential difficulty in accessing LGBTQ+ youth through traditional recruitment methods, a snowball sampling approach was deemed most appropriate. Initial participants, identified through LGBTQ+ community organisations known for their supportive environments, were invited to refer other eligible individuals from their networks. This method facilitates access to a hard-to-reach and potentially vulnerable population by leveraging existing social connections, thereby increasing trust and willingness to participate. While this approach limits the generalisability of findings due to potential homophily within networks, it maximises the likelihood of recruiting a sample with lived experience relevant to the research question, enabling in-depth exploration of attitudes towards therapy within this specific demographic. Ethical considerations, including ensuring participant anonymity and obtaining informed consent from both initial and referred participants, were rigorously adhered to throughout the recruitment process."

Scenario 2: Reaction time in visual perception tasks

Study Aim: To investigate fundamental cognitive processes, specifically how different visual stimuli affect reaction time. The focus is on the general principles of human perception rather than specific demographic differences.

Participant Characteristics: Healthy adults with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. A broad, relatively homogeneous sample is suitable.

Resource Constraints: Lab-based study, requiring participants to come to a specific location.

Ethics: Standard ethical considerations for experimental psychology.

Possible Sampling Method: Convenience Sampling (with acknowledgement of limitations) or Simple Random Sampling (if feasible).

Justification Rationale (Convenience): "This study on visual perception and reaction time utilised a convenience sample of undergraduate students enrolled in psychology courses at [University Name]. This method was chosen primarily for its practicality and efficiency in recruiting participants for a laboratory-based experiment within the constraints of a student research project. Undergraduate students are a readily accessible population for such studies, and their cognitive processes related to visual perception are generally considered representative of the broader young adult population for fundamental cognitive tasks. While acknowledging the limitations in generalisability beyond this specific demographic, the focus of the study was on establishing basic principles of visual processing, where age and educational background are less likely to introduce significant confounding variables. Rigorous control over experimental conditions and stimuli was maintained to maximise internal validity."

Scenario 3: Memory in older adults with cognitive decline

Study Aim: To examine the efficacy of a new intervention for improving memory in a specific clinical population. High internal validity and the ability to detect subtle changes are crucial.

Participant Characteristics: Older adults with diagnosed cognitive decline, potentially fragile and requiring careful ethical consideration.

Resource Constraints: Access to this population may be challenging, requiring collaboration with healthcare providers.

Ethics: Extreme care needed regarding consent, capacity, and potential distress.

Possible Sampling Method: Purposive Sampling (clinical referrals) or Quota Sampling (if specific subgroups of decline are targeted).

Justification Rationale (Purposive): "To investigate the impact of the novel memory intervention, a purposive sample of older adults diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was recruited through clinical referrals from local memory clinics at [Hospital Name]. This specific sampling method was employed to ensure that all participants met predefined diagnostic criteria for MCI, thereby maximising the internal validity of the study and enabling a focused examination of the intervention's effects within the target clinical population. Given the vulnerability of this population, this approach allowed for careful screening by medical professionals, ensuring participants' cognitive capacity to provide informed consent and minimise potential distress. While the findings may not be directly generalisable to the broader older adult population or those with different types of cognitive impairment, this method was essential for obtaining a clinically relevant and homogeneous sample, crucial for evaluating the intervention's specific efficacy."

🔍 Not sure what fits your design? Try our Sampling Method Picker – it guides you through the logic and gives you an editable APA-style rationale.

5. Template: How to Write a Justification Paragraph

Crafting a clear and concise justification paragraph can be simplified using a structured approach. Here's a plug-and-play sentence template that you can adapt for your specific study, followed by filled-out examples.

Template:

“This study used [sampling method] to recruit [participant group], based on [reasoning about accessibility, ethics, representativeness, or study aim]. While this introduces [limitation/potential bias], it supports [goal or feasibility of the study] and [how you addressed or acknowledge the limitation].”

Examples:

For a Lab Report (Convenience Sampling): "This study used convenience sampling to recruit undergraduate psychology students from [University Name], based on their immediate accessibility and the pragmatic constraints of a short-term laboratory experiment. While this introduces potential bias regarding generalisability to the broader population and limits the diversity of the sample, it supported the feasibility of data collection within the allocated timeframe and was considered appropriate for investigating fundamental cognitive processes not heavily reliant on demographic variability."

For a Project/Dissertation (Stratified Random Sampling): "To investigate the impact of socioeconomic status on academic achievement, this study used stratified random sampling to recruit adolescents aged 16-18 from two distinct socioeconomic strata (low-income and high-income) within [City Name]. This approach was chosen to ensure proportional representation from both groups, thereby enhancing the representativeness of the sample and allowing for direct comparisons between strata. While the initial identification of eligible participants and the logistics of random selection required significant effort, this method was crucial in reducing sampling bias and increasing the external validity of findings regarding socioeconomic disparities in education."

For an Ethics Proposal (Snowball Sampling for a Sensitive Topic): "This research proposes to use snowball sampling to recruit individuals who have experienced homelessness in [Specific City Area]. This method is justified due to the inherent difficulty in accessing and building trust with this vulnerable population through traditional random sampling techniques. While acknowledging that this approach may introduce selection bias due to participants' social networks and limit the overall generalisability, it is considered the most ethically sound and practically feasible method for reaching individuals who may be disconnected from formal services. Furthermore, this method helps to protect participant anonymity and foster a sense of security through peer referral, prioritising their welfare and enabling the collection of valuable qualitative data from a population rarely heard from in research."

6. Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even with a strong understanding of sampling methods, certain pitfalls can undermine your justification. Being aware of these common mistakes can help you avoid them.

Justifying After-the-Fact Rather Than Based on Design: A common error is to choose a method (often convenience sampling) out of practicality and then try to retroactively invent a robust justification. Your sampling method should be an integral part of your study design from the outset, not an afterthought. To avoid: Plan your sampling method concurrently with your research question, aims, and participant characteristics.

Using Convenience Sampling Without Acknowledging Bias: While convenience sampling is often necessary due to practical constraints, simply stating "it was convenient" is insufficient. The key is to acknowledge the inherent biases (e.g., lack of representativeness, over-representation of certain groups) and discuss how these biases might affect your findings or how you plan to mitigate them. To avoid: Always discuss the limitations of convenience sampling in your justification and consider how it impacts the generalisability of your results. Suggest ways future research could overcome these limitations.

Using Terms Interchangeably (e.g., Random vs. Randomised): "Random" sampling (e.g., simple random sampling) refers to the selection of participants from a population, ensuring everyone has an equal chance. "Randomised" (e.g., randomised control trial) refers to the assignment of participants to different experimental conditions. These terms are not interchangeable. To avoid: Be precise with your terminology. Understand the difference between random selection (sampling) and random assignment (experimental design).

Overstating Generalisability: It's tempting to claim your findings apply broadly, but if you've used a non-probability sampling method, your generalisability is inherently limited. Overstating it can weaken your methodological credibility. To avoid: Be realistic about the scope of your findings. Clearly state the population to which your results can reasonably be generalised. If your sample is specific, acknowledge this and discuss the implications. For instance, "Findings are generalisable to university students in [region]," not "Findings are generalisable to all young adults."

Ignoring Ethical Implications in Justification: Your sampling method has direct ethical implications, particularly when dealing with vulnerable populations or sensitive topics. Failing to mention how your chosen method aligns with ethical guidelines can be a significant oversight. To avoid: Integrate ethical considerations into your justification, explaining how your method prioritised participant welfare, confidentiality, and informed consent.

7. Simply Put: Better Justification = Stronger Study

In the landscape of psychological research, the choice and justification of your sampling method are not mere procedural details; they are foundational pillars of a well-designed study. A thoughtfully chosen and thoroughly justified sampling approach signals to your markers and supervisors that you possess a deep understanding of research methodology, a critical awareness of potential biases, and a commitment to the scientific rigor of your work.

Moving beyond the simplistic "because it was easy" mindset, a strong justification demonstrates that you've engaged in critical thinking about how your participant recruitment strategy aligns with your research aims, navigates real-world constraints, and accounts for ethical considerations. It shows that you understand the trade-offs inherent in any methodological decision and have made informed choices to maximise the validity and relevance of your findings within the practical limitations.

While tools and templates can provide valuable structure and guidance, the ultimate strength of your justification lies in your fundamental understanding of why you are choosing a particular method. By articulating this rationale clearly and comprehensively, you not only strengthen the methodological foundation of your psychology assignment or report but also enhance the overall credibility and impact of your research. Remember, a robust justification is a hallmark of a robust study.

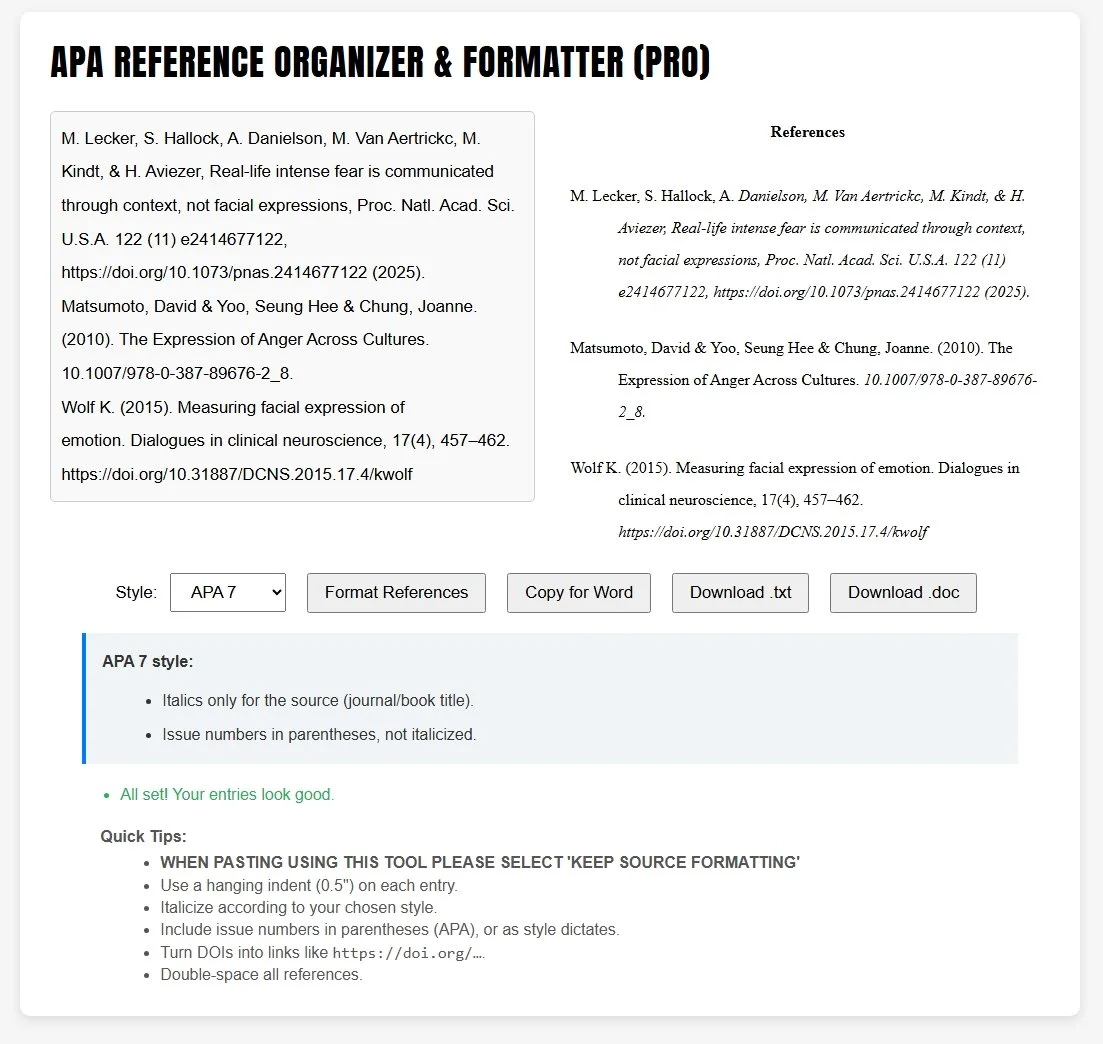

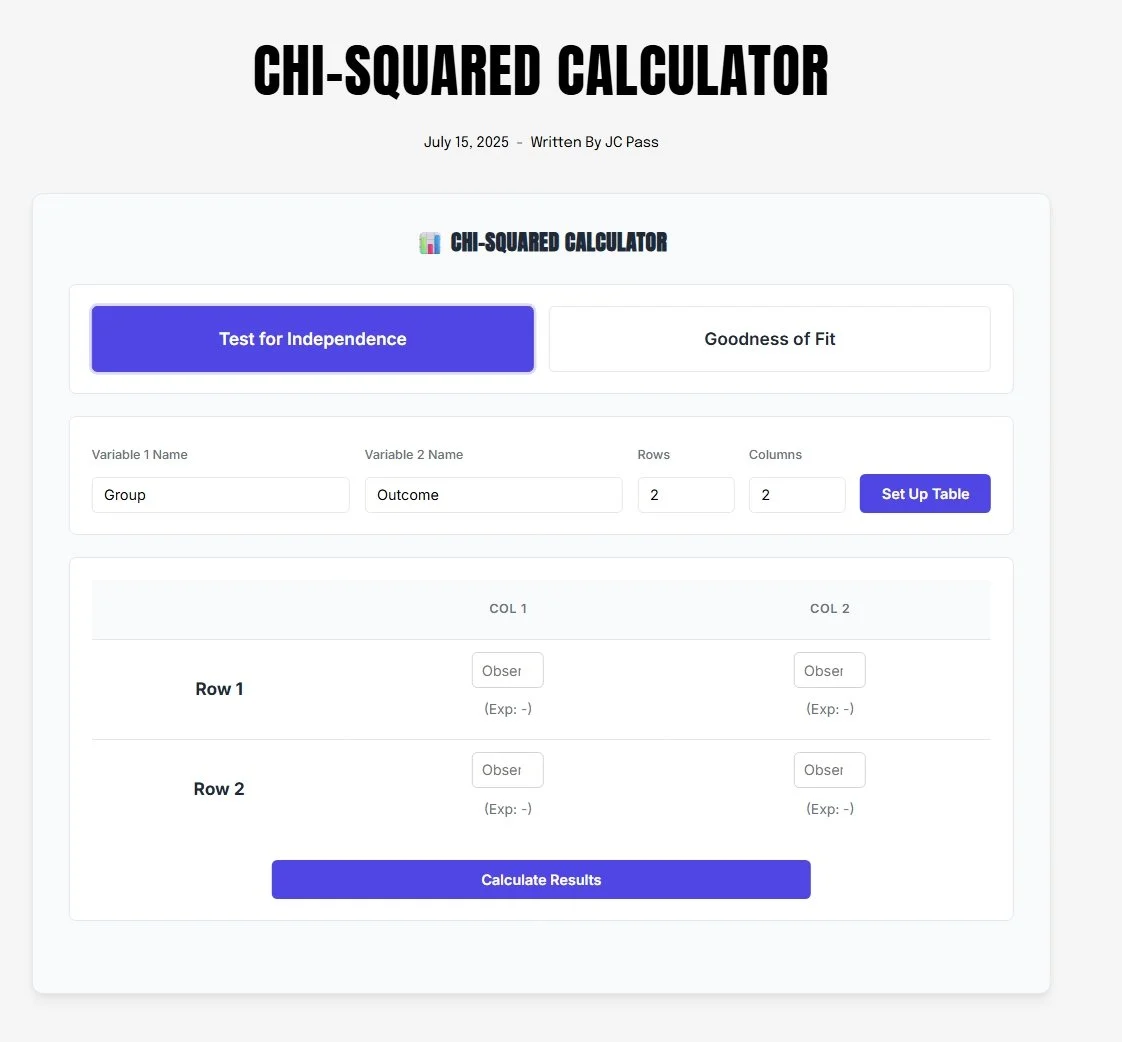

Need help with the tricky parts?

Our Premium Tools are built for psychology students who want to focus on ideas, not formatting. From APA-compliant tables and results to ethics checklists, sample size calculators, and consent form builders — we've got the hard parts covered.

Explore Premium Tools →8. References

Demystifying Participant Selection in Research Studies - Psychology Town

Sampling methods in Clinical Research; an Educational Review - PMC

What Is Non-Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples - Scribbr

How Stratified Random Sampling Works, With Examples - Investopedia

Stratified statistics: When and how to use stratified sampling - Statsig

Cluster Sampling | A Simple Step-by-Step Guide with Examples - Scribbr

What is Cluster Sampling? | Explanation, Pros & Cons, Steps - ATLAS.ti

Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques & Examples - Scribbr

3.2.3 Non-probability sampling - Statistique Canada

Purposive and Convenience Sampling | NCSC - National Center for State Courts

Convenience sampling method: How and when to use it? - Qualtrics

Understanding Non-Probability Sampling - Helio

Snowball Sampling | Division of Research and Innovation - Oregon State University

Non-Probability Sampling: Methods and Best Practices - SurveySparrow

What Is Quota Sampling? | Definition & Examples - Scribbr

How to Determine Sample Size - Qualtrics

Stratified Sampling - Omniconvert

Types of Sampling - Numeracy, Maths and Statistics - Academic Skills Kit