When Comedy Gets There First: Dumb and Dumber, Dunning–Kruger, and the Sociology of Confidence

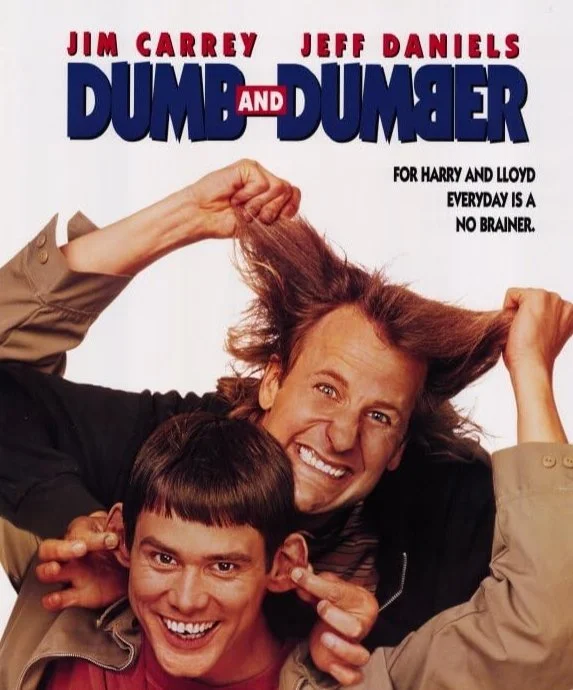

In 1994, Dumb and Dumber arrived as a broad, slapstick comedy built on the premise of two spectacularly unintelligent men blundering their way across America. Five years later, psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger formally described what is now known as the Dunning–Kruger effect. The timing invites a tempting provocation: did the film, unintentionally, sketch a blueprint for one of psychology’s most influential modern findings?

The answer is not that comedy predicts science, but something more revealing about how culture, psychology, and social structure interact. Long before a phenomenon is operationalised, measured, and peer-reviewed, it is often already circulating as a shared intuition. Dumb and Dumber is a case study in how media captures these intuitions, exaggerates them, and in doing so makes invisible cognitive mechanisms suddenly legible.

Ignorance Without Insight

The core of the Dunning–Kruger effect is frequently misunderstood. It is not merely that people can be wrong, or even confidently wrong. It is that the skills required to perform well in a domain are often the same skills required to recognise poor performance. When those skills are absent, self-evaluation collapses. Ignorance is not experienced as ignorance. It is experienced as clarity.

Lloyd Christmas and Harry Dunne embody this failure of metacognition. Their confidence is not performative or strategic. It is sincere. They believe they are clever, capable, and socially adept because they lack the internal tools required to question that belief. When plans fail, they do not update their models of the world. Instead, failure is reframed as bad luck, misunderstanding, or near-success.

This is crucial. Comedy often depicts stupidity as a deficit of information. Dumb and Dumber depicts it as a deficit of epistemic self-awareness. That distinction is exactly what later research formalised.

Confidence as a Social Signal

From a sociological perspective, the film also illustrates why overconfidence is socially effective, even when it is detached from competence. Confidence operates as a signal. In uncertain environments, people often use confidence as a proxy for knowledge. Lloyd’s assertiveness routinely positions him as the de facto leader of the pair, despite no evidence that his judgments are sound.

Harry, slightly less confident but equally incapable, defers to Lloyd not because Lloyd is correct, but because Lloyd appears certain. This dynamic mirrors real-world hierarchies in which authority emerges from presentation rather than expertise. The film exaggerates this for comic effect, but the mechanism is recognisable in workplaces, politics, and media ecosystems.

Sociologically, this reflects a broader structural problem: modern societies often reward confidence more reliably than competence. When evaluation is noisy, rushed, or mediated through performance rather than outcomes, those who speak decisively gain influence, regardless of accuracy. Dumb and Dumber distils this process into a two-person microcosm.

Mutual Reinforcement and the Closed Loop

One of the film’s most psychologically interesting features is that Lloyd and Harry are rarely isolated. They operate as a dyad. Each reinforces the other’s interpretations, assumptions, and confidence. Errors are not corrected but stabilised through agreement.

This is an early depiction of what later sociological and psychological research would describe as epistemic closure. When individuals with similar limitations validate one another, they form a self-sealing belief system. External feedback is dismissed, reinterpreted, or ignored. The group becomes resistant to correction not because it is hostile to evidence, but because it lacks the tools to process it.

In contemporary terms, this dynamic now scales far beyond two people. Online communities, algorithmic feeds, and fragmented media environments allow confidence-driven ignorance to be socially reinforced at scale. What Dumb and Dumber presents as an absurd road trip now resembles a structural feature of modern information systems.

Media, Exaggeration, and Cognitive Visibility

Why does comedy often seem to “see” these patterns before academia names them? The answer lies in method. Psychological science demands precision, controls, and cautious inference. Media operates differently. It amplifies patterns until they are unmistakable.

Dumb and Dumber removes mitigating factors that might obscure the cognitive mechanism. There is no learning arc. No moral reckoning. No gradual self-awareness. The characters remain confidently wrong from beginning to end. In real life, consequences usually intrude. In comedy, they are suspended. This allows the underlying cognitive structure to remain visible rather than being disrupted by adaptation.

In this sense, the film functions as a kind of cultural thought experiment. What happens if metacognitive failure is total and sustained? The answer is not chaos, but continuity. The characters persist, socially engaged, emotionally optimistic, and utterly disconnected from reality. That persistence is precisely what makes the Dunning–Kruger effect so troubling outside of fiction.

From Harmless Comedy to Cultural Warning

When Dumb and Dumber was released, its characters were read as harmless fools. Their ignorance posed no serious threat. They were socially marginal, economically powerless, and narratively contained. The audience could laugh without discomfort.

Three decades later, the same cognitive pattern feels less benign. The Dunning–Kruger effect has become a lens through which people interpret public discourse, institutional failure, and the spread of misinformation. The discomfort comes from recognition. We now encounter Lloyd-and-Harry dynamics in spaces that shape policy, culture, and collective outcomes.

The film has not changed. The social context has.

Psychology Catches Up to Satire

It is tempting to frame this as a case of art anticipating science, but that overstates the mystery. What actually happened is more mundane and more revealing. The phenomenon existed. People noticed it. Comedians exaggerated it. Psychologists later measured it.

Science did not invent the insight. It disciplined it.

This order matters. It reminds us that psychological constructs are not plucked from nowhere. They emerge from lived experience, social frustration, and repeated observation. Media often captures these patterns first because it is attuned to what people already sense but cannot yet articulate.

Simply Put

Revisiting Dumb and Dumber through the lens of psychology and sociology reveals it as more than a relic of 1990s comedy. It is an accidental case study in how ignorance, confidence, and social reinforcement interact. It shows us not just that people can be wrong, but why being wrong can feel indistinguishable from being right.

That is the unsettling lesson at the heart of the Dunning–Kruger effect, and the reason the film now reads less like farce and more like parable. When self-knowledge fails, confidence fills the gap. When confidence is rewarded, the gap widens. And when social systems amplify that confidence, comedy quietly turns into diagnosis.

The joke landed in 1994. The theory arrived in 1999. The consequences are still unfolding.

References (APA 7th)

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Turner, G. (2014). Understanding celebrity (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Farrelly, P. (Director), & Farrelly, B. (Director). (1994). Dumb and dumber [Film]. New Line Cinema.