What Makes a Christmas Film a ‘Christmas Film’? A Narrative Psychology Breakdown

What actually makes a film a Christmas film? Narrative psychology reveals that it’s far more than tinsel, snow and a calendar date. Christmas stories tap into ritual, nostalgia, redemption arcs, communal meaning-making and culturally shared myths — psychological ingredients that shape how audiences recognise a film as belonging to the festive canon. This breakdown explores the narrative patterns and cognitive mechanisms that define the Christmas genre.

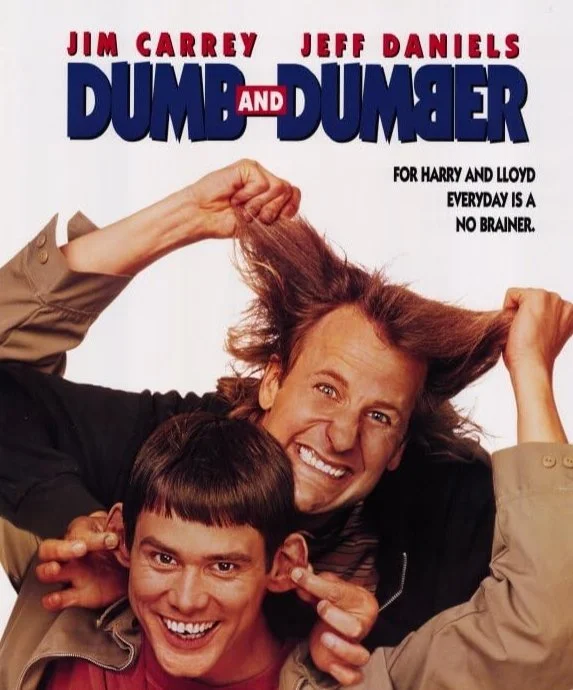

Every December, the annual debate resurfaces: Is Die Hard a Christmas movie? What about Harry Potter, Frozen, or anything involving snow and a mildly emotional ending? The internet is flooded with arguments, but beneath the memes lies a deeper question — how do our minds categorise narratives? Why do some films feel like Christmas, even when the plot barely mentions the holiday, while others that name-drop Christmas repeatedly leave us emotionally unmoved?

Narrative psychology offers a surprisingly precise answer. We recognise a Christmas film not by surface aesthetics but by the deeper psychological functions Christmas stories perform: ritualising emotion, reaffirming communal norms, and offering temporary suspension from the ordinary world. In other words, a Christmas film is not defined by what it shows, but by what it does to the viewer.

Let’s unpack the psychological architecture of the Christmas genre — and why certain stories become festive classics even without Santa, snow, or sleigh bells.

1. Christmas as a Narrative Schema: The Mental Blueprint of Festive Stories

Humans rely on schemas — cognitive templates — to organise information and categorise experiences. Just as we recognise a “fairy tale” by its archetypes, we recognise a “Christmas film” by the narrative roles it plays.

Research into schema theory (Bartlett, 1932; Rumelhart, 1980) shows that stories are understood not only through plot, but through familiar patterns that guide interpretation. Christmas films commonly activate schemas involving:

ritual (family gatherings, gift-giving, returning home)

renewal (reconciliation, forgiveness, second chances)

moral reorientation (the greedy becoming generous, the isolated becoming connected)

collective identity (belonging, community, the “spirit of Christmas”)

These themes act as cognitive signposts. The moment a narrative begins to evoke these patterns, the audience’s brain flags it as “Christmas-coded,” even if the plot never explicitly declares it.

This helps explain why Die Hard qualifies for many people — it features reconciliation with family, communal crisis resolved through bravery, moral redemption, and the ritual backdrop of a corporate Christmas party. The Christmas schema activates, even if Santa does not.

2. Liminal Time: Why Christmas Creates Psychological Space for Transformation

One of the strongest predictors of “Christmasness” is liminality — a transition period where normal rules are suspended. Anthropologist Victor Turner (1969) argued that ritual periods create social in-betweenness, allowing for extraordinary transformations.

Christmas is one of the West’s most powerful liminal landscapes:

work slows

behaviour norms loosen

relationships shift (reunions, confessions, reconciliations)

moral expectations intensify (“be kind,” “give back”)

identity becomes flexible (Scrooge can become good; Kevin McCallister can become brave)

Films leverage this liminality to create narrative permission for radical change. The grouch softens. The cynic believes. The lonely person finds connection. Christmas offers psychological cover for metamorphosis.

This is why many Christmas films are essentially redemption arcs wearing festive jumpers.

Even non-Christmas films that feel Christmassy — e.g., The Secret Life of Walter Mitty — often employ liminality: a temporary suspension of ordinary reality that enables personal growth.

3. Nostalgia: The Emotional Engine of the Christmas Genre

Nostalgia is one of the most potent emotional states associated with Christmas. Research shows that nostalgia is:

socially binding (Wildschut et al., 2006)

mood-boosting

identity-stabilising

and triggered strongly by seasonal rituals

Christmas films activate nostalgia through:

familiar narrative beats

music cues (bells, choirs, warm strings)

repetition (many are rewatched annually)

themes of childhood innocence

representations of “home”

Nostalgia acts as both comfort and emotional intensifier. Films like It’s a Wonderful Life, Home Alone, and The Muppet Christmas Carol rely on nostalgia not just as a feeling, but as a structuring principle.

A Christmas film is often less about the holiday, and more about remembering a previous emotional state associated with the holiday — safety, belonging, wonder, simplicity.

This mechanism explains why even modern Christmas films feel deliberately retro: they are attempting to evoke nostalgia for a past the viewer may not have personally lived.

4. Communal Morality: Christmas Films as Secular Sermons

Most Christmas films follow a predictable moral arc:

the isolated character reconnects

the selfish becomes generous

the disbeliever regains faith (in humanity, not necessarily religion)

the fractured family repairs

community triumphs over individual cynicism

These aren’t random tropes. They reflect collective moral narratives that psychologists argue societies use to teach prosocial behaviour (Haidt, 2012). Christmas films function almost as secular morality plays, transmitting cultural values such as:

generosity

empathy

forgiveness

communal responsibility

the importance of relationships

Even comedies like Elf or Arthur Christmas hinge on moral repair and communal cohesion. Christmas functions as a narrative excuse to push moral transformation without seeming preachy — because it’s built into the cultural script.

This also explains why films that emphasise spectacle without emotional or moral grounding rarely become classics. Christmas stories require emotional labour, not just aesthetic décor.

5. Myth and Magic: The Role of Belief in Festive Storytelling

Christmas films often operate in a space between realism and myth. Even non-magical stories lean heavily on symbolic logic:

improbable coincidences

miraculous timing

extremely convenient character reversals

This blends with what psychologists call magic realism schemas — patterns in which the impossible becomes metaphorically (or narratively) acceptable.

Children's films add literal magic (flying sleighs, living snowmen), but adult Christmas films also rely on mythic thinking, just expressed through emotional rather than supernatural miracles.

Belief is the keyword — belief in oneself, in others, in connection, in possibility.

Christmas films turn belief into a psychological device for narrative cohesion.

This is why a Christmas film can be fantastical (The Polar Express), grounded (Love Actually), comedic (The Grinch), or action-oriented (Die Hard), as long as it engages with the mythic frame of belief restored.

6. Aesthetic Symbols: Snow, Lights, Music — But Not Always Necessary

Most Christmas films use symbolic markers that activate seasonal concepts:

snow

warm lighting

family homes

red/green colour palettes

choirs

gift exchanges

communal meals

These symbols operate like cognitive shortcuts, triggering the Christmas schema quickly.

However, these symbols alone are not sufficient. Plenty of films contain snow, lights, or family gatherings without being Christmas films.

The aesthetic layer matters, but psychological function matters more.

A film becomes Christmassy only when symbol + narrative + emotion operate together.

Aesthetic cues simply accelerate schema activation, making the narrative feel instantly familiar and emotionally primed.

7. So… Is Die Hard a Christmas Film? A Psychological Classification

Narrative psychology gives a surprisingly neat answer:

A film is a Christmas film if its emotional, moral, and narrative functions rely on Christmas to work.

Using that framework:

Die Hard uses Christmas as a narrative catalyst (family reunion), emotional container (redemption), and symbolic backdrop (peace, togetherness disrupted by violence).

It activates schemas of liminality, reconciliation, and communal rescue.

The Christmas setting intensifies its themes of family repair and moral courage.

So yes — psychologically, Die Hard is a Christmas film.

Harry Potter films, in contrast, merely contain Christmas scenes. Their narratives do not depend on Christmas-specific psychological functions.

Simply Put

The question “What makes a Christmas film a Christmas film?” is not really about genre policing. It’s about how humans use stories to regulate emotion, reaffirm identity, and return to a psychological home base.

Christmas films endure because they perform essential emotional work:

nostalgia

connection

moral repair

ritual comfort

meaning-making

Whether the setting is a snowy village, a skyscraper under siege, or a suburban living room, Christmas films operate as annual emotional recalibrations, helping viewers locate warmth, memory, and community in a world that feels increasingly fragmented.

That’s why the genre survives. And why, every December, we find ourselves reaching for the same stories — not because they are festive, but because they make us feel human.

References

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage.

Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Aldine.