Hazbin Hotel and the Oddly Cheerful Logic of Restorative Justice

Restorative justice meets demonic show tunes as Hazbin Hotel uses its infernal setting to explore apology, accountability, and the occasional threat of angelic mass murder. The result is a surprisingly useful primer for anyone studying how people change.

Hell is not the first place most people look when searching for constructive models of conflict resolution. Yet Hazbin Hotel, Vivienne Medrano’s candy colored, demon populated musical series, makes the case that even the damned benefit from thoughtful approaches to wrongdoing. The show layers its comedy and spectacle over a premise that would not feel out of place in a criminology seminar: that harm should be repaired, people should be accountable, and communities do better when they reintegrate their troublemakers instead of tossing them into a cosmic waste bin. It is restorative justice with jazz hands.

Restorative justice (RJ) rests on the idea that crime is fundamentally harm. Laws may be broken, but the real injury lands on relationships and people. Instead of obsessing about punishment, RJ asks what must be done to repair that damage, address root causes, and reintegrate offenders. Howard Zehr, a central thinker in the field, argues that RJ “aims at helping offenders to recognize the harm they have caused and encouraging them to repair the harm, to the extent it is possible.” The University of Wisconsin’s Restorative Justice Project puts it even more bluntly: examine impact, involve those affected, and figure out how to put things back together while still holding the offender accountable.

Hazbin Hotel takes these ideas and drops them into a setting where the local culture leans heavily toward massacres, blackmail, and avant garde sins that mortal criminologists have not invented labels for yet. Through the ambitions of Hell’s princess, Charlie Morningstar, the series turns RJ principles into a flamboyant storyline. Her insistence that “any soul can change” might strike some of her peers as naïve, but it captures the heart of restorative justice better than many earnest brochures. If RJ theorists ever wanted a mascot, Charlie might be their unexpected champion.

The Restorative Premise of a Hotel in Hell

The central concept of Hazbin Hotel is absurd in the exact way that satire enjoys best. Charlie decides that the overcrowding problem in Hell can be solved not by extermination, which Heaven helpfully performs on a regular schedule, but by rehabilitation. Her solution is to open a hotel that doubles as a therapeutic retreat for sinners. It is a bold idea, if not one with a generous safety plan, and she describes it proudly as a “home of healing” and a “resort of restoration.” That sort of marketing language is usually found in spa pamphlets, but Charlie delivers it with such sincerity that one could almost forget she is speaking to an audience of demons.

Her mission statement echoes RJ’s core belief that people have the capacity to change. Crime and harm do not make someone irredeemable. They only indicate that repair is necessary. In the pilot episode, Charlie blithely asserts that “everyone can be redeemed, from the evil to the strange,” a line that would fit comfortably in RJ literature if one swapped “strange” for something less whimsical.

Hazbin Hotel draws a clear contrast between restorative thinking and punitive instincts. Most of Hell finds Charlie’s idea ridiculous. News anchor Katie Killjoy treats her like a delusional social worker who wandered into the underworld by accident. When the demon overlord Alastor appears and offers his help purely for the fun of it, Charlie agrees anyway. Her reasoning is simple: she cannot turn someone away because it contradicts everything she believes. RJ programs rely on voluntary participation, and in this exaggerated parallel world, even a supernatural villain is invited to choose rehabilitation over chaos.

While Charlie’s hotel lacks structured mediation rooms and well trained facilitators, it shares RJ’s foundational assumption. Change is possible when people are treated as stakeholders in their own future. Charlie is not blind to danger, but she prefers hope to fear. Hazbin Hotel adopts this restorative lens as its narrative engine, which might be the most surprising twist in a show that also contains giant mechanical serpents and sentient radios.

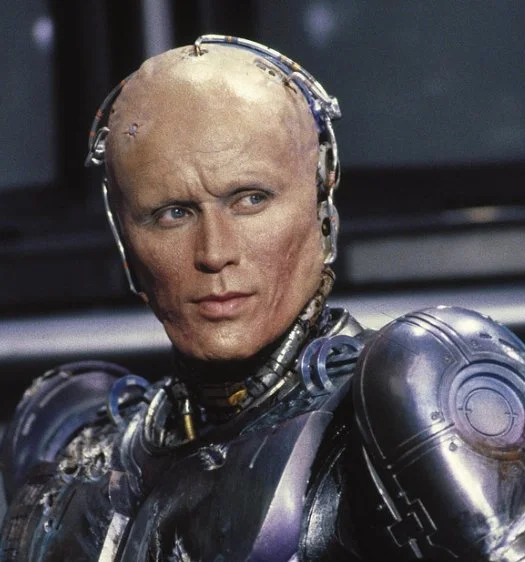

Charlie Morningstar as a Restorative Idealist

In an environment saturated with cynicism, Charlie stands out like a motivational poster that has wandered into a metal concert. The daughter of Lucifer, she takes on the role of Hell’s most determined rehabilitation specialist. Her optimism is so persistent that viewers may suspect she is powered by an internal generator of propulsive cheer.

Her philosophy aligns closely with the tenets of restorative justice. She believes that everyone deserves the chance to prove they can be better. This resembles the RJ principle of inviting offenders to take responsibility in a setting where dignity is preserved. Charlie insists on accountability, though she issues her expectations with smiles and songs rather than formal agreements.

When Alastor offers his assistance, Charlie allows it with ground rules. No secret deals. No tricks. No undermining her leadership. It is accountability dressed in cartoonish politeness. In another scene, Charlie conducts an impromptu lesson on how to apologize. She announces that becoming a better person begins by admitting when you are wrong. If RJ experts ever needed a pop culture example of offender acknowledgment, Sir Pentious’s shaky but sincere apology would qualify.

Charlie also acts as a facilitator. She organizes group activities that loosely resemble restorative circles, though the clapping sequences and musical numbers would challenge most community mediation programs to keep a straight face. Characters introduce themselves, share personal tidbits, and gradually see one another as people instead of adversaries. Beneath the absurdity lies a recognizable goal: build community and empathy so that change becomes possible. RJ research repeatedly notes that community plays a vital role in supporting both victims and offenders. Hazbin Hotel gives this idea a supernatural makeover by letting demons bond over shared struggles and questionable life choices.

Vaggie as the Voice of Caution and Hurt

No restorative process is complete without the voice that snarls, “Absolutely not.” In Hazbin Hotel, that role belongs to Vaggie. She is Charlie’s girlfriend and chief protector, and she reacts to dangerous demons with all the enthusiasm of a homeowner discovering termites. When Alastor appears, Vaggie insists he is irredeemable. Her skepticism channels the emotions real victims feel toward offenders: fear, distrust, and a desire for safety above all.

RJ scholars such as Martha Minow emphasize that victims are not obligated to forgive. Their participation must be voluntary and respected. Hazbin Hotel takes this seriously, albeit in its own dramatic way. Vaggie’s anger is treated as valid. She is not mocked for refusing to trust Alastor. Her perspective offers balance to Charlie’s idealism, preventing the show from implying that forgiveness is automatic or easy.

Yet Vaggie is also willing to change her mind when offenders show genuine contrition. When Sir Pentious apologizes and sets aside his villainy, she grudgingly accepts him. Her shift reflects a familiar RJ pattern: victims often soften when they see meaningful accountability. Hazbin portrays this process with heightened humor, but the emotional principle remains intact.

Vaggie also models another RJ value. She encourages Charlie to give people space to process their own pain, especially when Angel Dust’s traumatic history is revealed. Restorative justice emphasizes the emotional needs of all involved. Vaggie’s sensitivity shows that caution and compassion can coexist without moral contradiction.

Angel Dust and the Messy Road to Personal Repair

Some characters in Hazbin Hotel seem tailor made for a case study in restorative transformation. Angel Dust is the most prominent example. A flamboyant spider demon, he is both a victim and an offender. His history includes exploitation by others and harm he has caused in return. RJ frameworks often address cases where trauma and wrongdoing are intertwined. Angel’s arc could be used as a teaching tool, though faculty in a criminology department would need to skip certain details to keep the accreditation board comfortable.

At first, Angel is uninterested in redemption. Substance abuse, petty crime, and sarcasm rank higher on his priority list. Charlie, however, treats him as part of her restorative community. She offers support without excusing his behavior. When his traumatic childhood is exposed to humiliate him, she responds with unwavering empathy. She does not absolve his actions, but she understands the context that shaped him.

Over time, Angel chooses to confront his addictions and seek healthier paths. He apologizes for the harm he has caused, though not always on the first try. This portrayal aligns closely with RJ’s emphasis on addressing root causes and supporting gradual change. Anyone expecting a quick transformation will be disappointed, which is entirely appropriate. RJ takes time. So does getting clean in a place where narcotics are marketed the way candy is marketed in the mortal world.

Angel’s journey shows that accountability is not a single moment. It is an ongoing process involving setbacks, support, and honesty. Hazbin depicts this with musical numbers and dramatic flair, but the heart of the process would be recognized by any RJ facilitator.

Alastor and the Restorative Value of Voluntary Chaos

Alastor, also known as the Radio Demon, participates in Charlie’s mission for reasons that are best described as recreational malevolence. He does not seek redemption. He simply finds the project amusing. Yet his unpredictable presence highlights another RJ insight. Not everyone in a restorative setting participates out of pure moral awakening. Sometimes stakeholders join for practical, social, or self serving reasons. They may still help.

Alastor assists Charlie in keeping the hotel functional. He supports the community, even if he does it while humming static filled tunes. He enforces certain norms, protects the group from other villains, and grudgingly honors Charlie’s rules. His compliance is not heartfelt, but it is cooperation. RJ models often rely on community members who are not saints. Hazbin Hotel expands this notion by showing a demon overlord who helps maintain order because it entertains him.

Other misfits follow similar paths. Sir Pentious shifts from enemy to eager participant. Husk, dragged into service by Alastor, eventually finds value in the group. Niffty joins as a whirlwind of enthusiasm and cleans every surface in sight. Together, they form a community that loosely mirrors the supportive networks central to RJ theory. Hazbin exaggerates this into a comedic ensemble, yet the relational dynamic is sincere.

Forgiveness, Harm, and What Counts as Real Accountability

Forgiveness in Hazbin Hotel is not compulsory. Charlie may believe in universal redemption, but the narrative respects the boundaries of those who do not feel ready to forgive. When villains like Vox and Valentino show no sincerity, no one offers them absolution. Hazbin underscores that forgiveness cannot be extracted like a confession from a suspect in an interrogation room. It must be given freely and honestly.

The show pokes fun at empty apologies. For example, a staged apology spectacle is presented for the public, complete with dramatic lighting. The insincerity is obvious. Hazbin contrasts this farce with genuine, unscripted apologies. When Sir Pentious admits his wrongdoing and expresses regret, the moment is heartfelt and transformative. Real accountability is presented as difficult, vulnerable, and meaningful.

Similarly, the community responds differently to those who demonstrate change. Once Angel begins sincere efforts toward sobriety and honesty, the hotel residents show renewed trust. Vaggie relaxes her guard. Charlie beams like a proud counselor. RJ practitioners would recognize this pattern. Reintegration works when the offender’s actions show commitment rather than performance.

Hazbin also highlights the importance of truth telling. Characters reveal painful history and motivations. These disclosures allow others to understand the emotional landscape behind harmful actions. RJ circles often focus on truth telling to deepen empathy and inform meaningful repair. Hazbin embraces this approach, although with more singing and significantly more glitter.

The Contrast with Punitiveness: Heaven’s Extermination

If Hazbin Hotel were a debate between restorative and retributive justice, Heaven would be the side that insists loudly that consequences must be swift, spectacular, and ideally televised. Every year, Heaven dispatches angels to exterminate a swath of Hell’s population. The ritual is treated as routine maintenance, like clearing out a garage, except the garage is full of sentient beings and the brooms are divine energy weapons.

This annual purge is retributive justice distilled to its sharpest point. It operates through a simple logic. Sinners are bad. Sinners stay bad. The only responsible action is to eliminate them. No questions. No context. No recognition that harm is a complex social phenomenon. Just fire from the sky and a firm belief that cleanliness is next to godliness.

Charlie’s hotel stands in direct opposition to this philosophy. Where Heaven prefers erasure, Charlie prefers engagement. Where Heaven offers no opportunity for accountability or transformation, Charlie builds an entire structure dedicated to providing it. She replaces extermination with conversation, annihilation with apology tours, and cosmic violence with a community bulletin board.

The show uses this contrast as its clearest dramatic device. It gives viewers a concentrated image of retributive justice: efficient, decisive, and completely uninterested in whether it actually solves anything. After all, the exterminations continue year after year. Heaven is not creating safety so much as performing it.

Charlie’s model, while messy and frequently endangered by interpersonal drama, actually aims to reduce the conditions that justify punishment in the first place. By supporting offenders through acknowledgment, honesty, and peer involvement, she attempts to break cycles of violence rather than reset them with sanctified force.

Hazbin Hotel’s narrative backbone is therefore an extended argument. Retribution is simple, predictable, and sterile. Restorative justice is difficult, unpredictable, and humanizing. Heaven believes it is managing a population. Charlie believes she is supporting a community. The series gently suggests that only one of these methods has a chance of making Hell safer.

In a world full of demons, the irony is not subtle. The angels are the ones committed to destruction, while the damned experiment with rehabilitation. Psychology and law students can consider this a slightly flamboyant reminder that punitive systems may feel satisfying in the short term, but they rarely achieve what restorative systems attempt: actual change.

Hazbin Hotel makes this point with all the seriousness of a musical comedy that refuses to treat redemption as a lost cause. The contrast is sharp, loud, and built directly into the architecture of the story. And as the series progresses, it becomes clear that the structural argument is not accidental. It is the foundation upon which the entire narrative—and Charlie’s relentless optimism—stands.

Hazbin’s Approach Compared with Real Restorative Justice

While Hazbin Hotel offers a surprisingly faithful emotional blueprint of restorative justice, it does not pretend to model RJ practices literally. There are no official mediation sessions, no formal agreements, and no paperwork. There is music. There are theatrical exercises. There are demons who probably should not be allowed near a conference room. What the show captures, instead, are the psychological principles behind RJ.

Restorative justice emphasizes community involvement, personal responsibility, healing, and transformation. Hazbin presents each of these through heightened absurdity. Charlie stands in for a facilitator, her hotel functions as an experimental rehabilitation center, and her group of demons represents a community that renegotiates norms through trial, error, and spirited argument.

The show also explores systemic considerations. Charlie’s later efforts to convince Heaven to reconsider its extermination policy reflect RJ’s interest in structural change. Restorative justice does not operate in a vacuum. It requires buy in from larger institutions. Hazbin portrays this with tongue in cheek drama. Heaven eventually pauses its violent interventions, in part because Charlie’s project demonstrates that change in Hell is possible. It is a rare moment when celestial politics mirror graduate school lectures on justice reform.

While Hazbin Hotel embellishes the concept, it still embodies RJ’s central ethos: people are more likely to improve when they are guided, supported, and treated with dignity. Punishment may stop a behavior, but it rarely repairs harm. Hazbin argues that even in a world filled with demons, repair is the more interesting option. And sometimes it even works.

What Have We Learned? A Handy Recap for the Academically Ambitious

For students of law, psychology, or anyone who has ever wondered how demons might model responsible citizenship, the following bullet points summarize the key ideas explored:

Restorative justice treats wrongdoing as harm to people and relationships, not as a cosmic scoreboard for punishments.

Hazbin Hotel reframes this by placing rehabilitation at the center of a setting that usually prefers explosions.

Charlie Morningstar functions as a relentlessly optimistic facilitator who believes that accountability works better when offered with empathy and the occasional musical number.

Vaggie represents the perspective of hurt parties who need time and safety before they consider forgiveness. She also demonstrates that skepticism is not an obstacle to RJ; it is an essential ingredient.

Angel Dust provides a case study in trauma informed restorative justice. His arc illustrates that accountability and healing are possible even when the offender struggles with shame, addiction, and unsolicited emotional transparency.

Alastor and the other misfit residents show that stakeholders may participate for mixed motives and still contribute to a restorative community.

Genuine apologies matter. Performative apologies, no matter how well lit or theatrically staged, do not.

RJ relies on community involvement. Hazbin achieves this with group rituals, shared vulnerability, and the occasional property damage.

Forgiveness is never demanded. It emerges only when accountability is sincere and support is real.

Structural change is part of the RJ process. In the show, this includes convincing Heaven to reconsider its long standing policy of mass destruction.

Most importantly: even a setting defined by eternal punishment can reveal the potential of RJ when someone insists on trying it, even if that someone is a demon princess with a fondness for show tunes.

Simply Put

Hazbin Hotel may be a supernatural black comedy, but beneath its neon surface lies a surprisingly disciplined engagement with restorative justice. Charlie Morningstar’s mission to rehabilitate sinners functions as a parable of healing, accountability, and community building. The series illustrates RJ principles through character arcs filled with remorse, resistance, growth, and occasional musical outbursts.

Vaggie represents the protective caution of victims who require safety and time. Angel Dust shows the tangled relationship between trauma and responsibility. Alastor demonstrates that even unenthusiastic participants can support communal goals in unpredictable ways. Together, the ensemble transforms a hotel in Hell into a laboratory for social repair.

By the time angels begin to reconsider their punitive strategies, the show has made its point. Healing is messy, slow, and difficult, but it is often more effective than punishment. RJ scholars might not adopt Hazbin Hotel as a training tool, but they would recognize its themes instantly. Hazbin suggests that even the worst among us might change if someone bothers to give them the chance.

It is a strangely hopeful message wrapped in sardonic humor and musical theater. And in its own infernal way, it makes the case that restorative justice is not simply a legal philosophy. It is a way of imagining people as capable of becoming better, even when everything about their circumstances suggests otherwise. Hazbin Hotel simply adds the detail that sometimes the path to redemption starts with a song, a sincere apology, and a princess of Hell who refuses to give up on anyone.

References

Braithwaite, J. (2002). Restorative Justice & Responsive Regulation. Oxford University Press.

Marshall, T. F. (1999). Restorative justice: An overview. London, England: Home Office.

Minow, M. (1998). When should law forgive? Harvard University Press.

Zehr, H. (2015). The little book of restorative justice (2nd ed.). Good Books.