Slay the Princess and the Ethics of Narrative Control

“She will destroy the world. Slay her.”

– The Narrator

When a game opens with such a stark command, the expectation is clear: You, the player, are to slay her? The princess must die? Following the immediate sense of cognitive dissonance, the doubt, the hesitation, Slay the Princess quickly escalates beyond established psychological tropes and down a path far less walked. What begins as a seemingly simple task quickly spirals into a philosophical and moral labyrinth, where the lines between saviour and executioner, reality and fiction, free will and manipulation blur into nothingness.

At its core, Slay the Princess isn’t about slaying anyone — it’s about the narrative structures that shape morality, and the unsettling realization that choice itself may be an illusion.

This essay explores how Slay the Princess engages with themes of moral agency, psychological fragmentation, and ethical determinism through a brilliant subversion of fantasy tropes. By placing players in an ambiguous, surreal, and recursive world, it forces them to question not just what’s “right,” but whether morality is even possible when the terms are constantly shifting.

A Princess, a Cabin, and a Knife

Developed by the team behind Scarlet Hollow, Slay the Princess is a deceptively simple visual novel with branching paths, minimalist visuals, and haunting voice acting. The setup is a direct subversion of the classic fairy tale: a lone cabin in the woods, a princess chained in the basement, and you — the would-be hero — sent to kill her.

The reason? She’ll destroy the world. Or so the narrator insists.

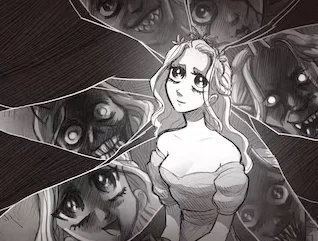

From the moment you approach the cabin, doubt begins to set in. The princess is calm, articulate, even kind. The voice guiding you becomes erratic and threatening. Multiple inner voices — fragments of your own psyche — start to argue. With each decision, reality cracks further, until you're no longer sure who the threat truly is: the narrator, the princess, or yourself.

What follows is a descent into a metafictional nightmare. Depending on your choices — whether you kill, hesitate, ally with, or try to understand the princess — the story loops, resets, and reshapes itself. The princess returns in new forms: monstrous, alluring, manipulative, or innocent. Your own inner voices emerge as characters — Skeptic, Paranoid, Hero, and others — each urging a different path, none of which feels wholly trustworthy.

There is no stable truth here. Only patterns of conflict, reformation, and uncertainty. And through that, the game builds its moral landscape not on right and wrong, but on the instability of meaning itself.

The Core Moral Tension: Choice Without Clarity

At the heart of Slay the Princess lies a moral paradox: can you be held ethically accountable for choices made under coercion, misinformation, or illusion? The game deliberately strips away reliable context. You’re told the princess will end the world, but offered no evidence. You’re told she’s imprisoned for your safety, but she’s chained and pleading.

In one version of events, killing her saves the world — in another, it dooms it. Sometimes she’s clearly manipulative; other times, she seems tragically misunderstood. Every “choice” becomes less a moral action and more a wager on incomplete information. This isn’t a hero’s journey — it’s a prisoner’s dilemma between you, the narrator, and your own psyche.

The game’s brilliance lies in its refusal to offer a “true” path. Unlike most morality-based games that use binary systems (good vs. evil, paragon vs. renegade), Slay the Princess presents morality as a shifting narrative construct — the rules change, and so does the world. And you, the player, must either adapt, resist, or surrender.

Psychological Fragmentation: Who Are You Really Playing?

Your internal voices — Hero, Paranoid, Voice of the Cold — serve as both companions and agitators. Each represents a different moral or psychological impulse: duty, fear, rationality, empathy. Their presence externalizes the inner moral debate players often experience silently. In a sense, you're not playing a character — you're watching a fractured self argue with itself over what’s right.

This reflects a deeply human psychological truth: we are not internally unified. When confronted with a difficult moral decision, we don’t operate from a single ethical code — we negotiate among many, shaped by emotion, logic, memory, and instinct. The game turns this internal moral chaos into literal dialogue, and even lets these voices overpower each other in different timelines.

The princess, too, is fragmented. Her various incarnations mirror the player’s moral stance. Try to save her, and she becomes soft and vulnerable. Try to kill her, and she becomes monstrous. The game implicitly asks: Are you shaping her nature, or is your perception being warped?

Deconstructing Moral Philosophies in a Shifting World

If we examine Slay the Princess through traditional ethical lenses, we find them all wanting. Consider:

Deontology (duty-based): You’re told it’s your duty to kill the princess — but who grants this duty? The narrator? Can duty exist without trust?

Utilitarianism (outcomes-based): You’re told her death prevents the apocalypse — but no proof exists. Many timelines end in ruin no matter what you choose. The calculus is broken.

Virtue Ethics (character-based): Can you be virtuous when your identity is unclear, your values fractured, and your actions constantly rewritten?

In this way, the game critiques ethical systems that assume moral clarity or stable identity. You’re not a hero. You’re not even a fixed “you.” You’re a shifting collection of impulses reacting to a shifting narrative, and the rules of engagement are obscured. Slay the Princess shows us the limits of ethical reasoning when narrative structure itself is the source of instability.

The Narrator as Authoritarian Morality

The Narrator in Slay the Princess isn’t just a voice — he’s the embodiment of moral absolutism, demanding obedience in the name of the greater good. He mocks dissent, scolds curiosity, and becomes increasingly hostile if you defy him. In some paths, he rewrites reality entirely to punish or correct your choices.

This authoritarian voice mirrors how many real-world systems present morality: as fixed, externally imposed, and binary. The Narrator insists on a single truth — kill the princess or the world dies — but his increasing desperation and narrative manipulation reveal a deep fragility. He isn’t a god; he’s a system desperately trying to maintain control in the face of player defiance.

The game’s moral arc, then, becomes not about whether to kill the princess, but whether to accept moral authority from an untrustworthy source. It’s a game about resisting imposed morality — and about what fills the void when certainty collapses.

Player Reaction and Moral Discomfort

One of the most telling aspects of Slay the Princess is how players interpret the story. Some feel betrayed. Others feel liberated. On Reddit and forums, discussions swing wildly:

“She had to die. She manipulated me.”

“I tried to save her, and it felt like the right thing, but I was punished.”

“I just wanted a version where we could talk.”

These reactions reveal the deep emotional investment players bring to unclear moral landscapes. When games deny clean victory or ethical validation, players confront their own assumptions: Do I trust authority? Do I value innocence over risk? Do I need to understand before I act?

By refusing to confirm any player’s moral stance, Slay the Princess becomes a mirror — not just for the character’s psyche, but for the player’s.

Simply Put: Morality in a Collapsing Story

Slay the Princess is not a game about killing or saving a princess. It’s a game about what happens to morality when the story falls apart. By embedding the player in a recursive, unreliable narrative filled with fractured identities and ambiguous outcomes, it challenges the very foundation of ethical decision-making.

In a world where choice is suspect, truth is mutable, and selfhood is unstable, Slay the Princess doesn’t ask whether you’ll make the right decision. It asks what you’ll become in the process of choosing — and whether that matters in the end.

Perhaps the princess is the world. Or the truth. Or your own moral center, chained in the dark. Perhaps slaying her is mercy. Or murder. Or liberation. The game won’t tell you. And maybe, that’s the most honest morality of all.

Explore how Slay the Princess subverts the stereotypical princess trope, drawing on psychological theories and peer-reviewed sources to analyse its impact on perceptions of gender and agency.