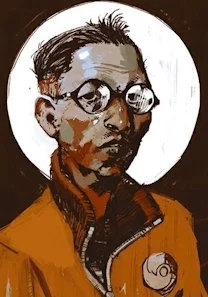

The Enigmatic Mind of Spike Spiegel: A Psychological Analysis

Spike Spiegel, the enigmatic bounty hunter at the heart of Cowboy Bebop, stands as one of the most complex and enduring characters in modern animation. Created by Shinichirō Watanabe, Cowboy Bebop (1998) is a Japanese anime that masterfully blends science fiction, film noir, jazz improvisation, and existential philosophy. Set in a futuristic world where humanity has colonized the stars, the series follows the crew of the spaceship Bebop as they navigate bounty hunting, personal demons, and existential questions of identity.

Spike’s character is defined by duality: he is effortlessly cool yet deeply haunted. His sardonic humour, martial arts prowess, and detached demeanour captivate viewers, but beneath the surface lies a man grappling with trauma, loss, and an existential struggle to find meaning. This internal conflict is further complicated by the relationships he forms with his crew—Jet Black, Faye Valentine, Edward, and the corgi Ein—who function as a surrogate family of sorts. His story is a rich tapestry shaped by cultural influences, from Japanese existentialism and Buddhist philosophy to Western film noir and jazz aesthetics.

This article delves into Spike Spiegel’s psyche through the lenses of psychoanalysis, Jungian archetypes, existential psychology, and cultural context. By examining his relationships, key moments, and thematic resonance, we explore why Spike remains a timeless figure in the annals of storytelling.

Major Plot and Character Spoilers Ahead

Character Background

Spike Spiegel’s life is one of fragmentation and duality. As a former member of the Red Dragon Syndicate, a powerful criminal organization, Spike was embroiled in a life of violence, betrayal, and forbidden love. His affair with Julia, the partner of his best friend and rival Vicious, led to a chain of tragic events. Forced to fake his own death, Spike left behind his old life, yet his past relentlessly pursues him.

Aboard the Bebop, Spike exudes a devil-may-care attitude. He is charming, sardonic, and recklessly confident but emotionally distant, masking his vulnerability with humour and bravado. Despite his aloofness, the Bebop crew becomes a kind of chosen family, and their interactions reveal cracks in Spike’s armour. His memories of Julia and confrontations with Vicious tether him to a life he wishes to escape, culminating in his fateful motto: “Whatever happens, happens.”

Spike’s defining moments, particularly his final confrontation with Vicious in The Real Folk Blues, reveal a man caught between life and death, hope and despair. As the series progresses, Spike’s fatalism grows, yet his journey is not just about succumbing to despair—it is about the struggle to find meaning amidst chaos.

Psychological Analysis

Freud’s Psychoanalysis: The Shadow of Repressed Trauma

Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory offers a lens to examine Spike’s inner turmoil. His detachment, recurring dreams of Julia, and fixation on the past reflect Freud’s concept of repressed trauma. Spike’s cavalier attitude and risk-taking behaviour serve as defence mechanisms, masking deep-seated pain. His refusal to fully confront these emotions allows his past to haunt him, creating a cycle of avoidance and confrontation.

However, Spike’s coping mechanisms are not purely escapist. His reckless behaviour and existential defiance—best captured in the line “I’m not going there to die; I’m going to find out if I’m really alive”—suggest a man grappling with the impermanence of life. Freud’s theories help illuminate Spike’s internal struggle between repressing his trauma and the unconscious compulsion to revisit it.

Jungian Archetypes: The Tragic Hero and the Anima

Carl Jung’s archetypes provide another perspective on Spike’s psyche. Spike embodies the tragic hero archetype—a flawed, charismatic figure whose internal conflict leads to his downfall. His journey is defined by a struggle to reconcile his fractured identity: the man he was in the Syndicate and the man he hopes to become.

Julia serves as Spike’s anima, the feminine archetype representing his inner desires and potential for wholeness. However, Julia is not just an idealized projection; her independence and choices shape the story’s broader themes of agency and sacrifice. She symbolizes the life Spike could have had—a life of love and redemption—but also the impossibility of reconciling his past and present. Her death cements this impossibility, leaving Spike untethered and adrift.

Existential Psychology: The Search for Meaning

Spike’s worldview reflects existentialism, particularly Viktor Frankl’s belief that humans are driven by the search for meaning, even amidst suffering. Spike’s risk-taking and refusal to confront his emotions reveal a man yearning for purpose. His journey is both a quest for closure and a dangerous dance with self-destruction.

Key moments, such as his confrontation with Vicious in Ballad of Fallen Angels and his cryptic musings in Jupiter Jazz, highlight Spike’s existential struggle. His final line in the series—“Bang”—is as much a declaration of acceptance as it is an acknowledgment of life’s transience. Through Spike, Cowboy Bebop explores the costs and rewards of the search for meaning in a chaotic universe.

Relationships: A Surrogate Family

While Spike projects indifference, his relationships with the Bebop crew reveal his capacity for connection and growth:

Jet Black: As a former cop, Jet serves as Spike’s partner and moral foil. Their camaraderie is built on loyalty and trust, though Jet’s pragmatic nature often clashes with Spike’s recklessness. Despite their differences, Jet’s quiet concern for Spike underscores the unspoken bond they share.

Faye Valentine: Faye’s own struggles with identity and loss parallel Spike’s, leading to a complex and often adversarial dynamic. Their banter masks mutual vulnerability, and in rare moments of honesty, their shared longing for belonging shines through.

Edward and Ein: While less central to Spike’s arc, Ed and Ein bring levity and warmth to the Bebop. Their eccentricity and loyalty subtly underscore Spike’s hidden capacity for care.

These relationships highlight Spike’s complexity. While he resists forming attachments, his actions often betray a quiet care for his crew, suggesting a glimmer of hope amidst his fatalism.

Symbolism, Culture, and Themes

Spike’s story is shaped by a fusion of cultural influences. The series’ noir aesthetic, jazz-inspired rhythm, and postmodern storytelling create a rich backdrop for his journey. Spike’s existential struggle echoes the Japanese concept of mono no aware—a bittersweet awareness of life’s impermanence.

Recurring motifs, such as the rose, symbolize love and transience, mirroring Spike’s fleeting moments of connection and the inevitability of loss. Similarly, his improvisational approach to life reflects the jazz ethos of resilience and adaptation. His final showdown with Vicious, steeped in mythic antihero tropes, explores themes of sacrifice, redemption, and the tension between individual desire and greater purpose.

Simply Put

Spike Spiegel is a masterclass in character design, blending psychological depth with universal themes of love, loss, and redemption. Through Freud, Jung, and existential psychology, we uncover a man as compelling as he is tragic, a reminder that the search for meaning often comes at a cost.

Yet Spike’s story is not just about despair; it is about resilience. His relationships, moments of humour, and ultimate confrontation with his past suggest that meaning is found in the journey itself, even when closure remains elusive.

As the final notes of Blue play over Spike’s fallen body, we are left with the same questions that drove him: What does it mean to truly live? And can we move forward without letting go of the past? For Spike Spiegel, and for us, the answers lie in the spaces between.

References

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his symbols. Dell.

LaMarre, T. (2009). The anime machine: A media theory of animation. University of Minnesota Press.

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Watanabe, S. (Director). (1998). Cowboy Bebop [TV series]. Sunrise.