Lisa: The Painful and the Ethics of Ruin

“I've been dead for 35 years. Today is the day I live.”

– Brad Armstrong

You’re given a choice. A man has taken your companion hostage. He tells you to make a decision: lose your arm, or let your friend die.

It’s not a bluff.

And if you think there’s a “right” answer, you haven’t played Lisa: The Painful.

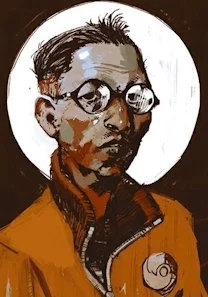

This isn’t a game about being a hero. It’s about surviving long enough to forget what that word means. Released in 2014 by Dingaling Productions (now LoveBrad Games), Lisa: The Painful is a post-apocalyptic RPG stitched together with equal parts black comedy and psychological horror. It’s a grotesque portrait of a broken man in a broken world, where morality isn’t just grey — it’s gone, buried somewhere under guilt, trauma, and the bodies you’ve left behind.

This article explores how Lisa: The Painful dissects morality through the lens of trauma, addiction, and survival. It doesn't ask what’s right or wrong — it shows you what’s left after you’ve crossed every line.

The World Has Ended, and It Deserved To

Lisa is set in Olathe, a desolate wasteland where every woman on Earth has mysteriously vanished. Society has collapsed into a feral parody of masculinity: gangs, cults, perverts, sadists — all fueled by desperation, drugs, and a total absence of hope.

You play as Brad Armstrong, a middle-aged, Joy-addicted martial artist who discovers an infant girl — the last known female — and raises her in secret as his adopted daughter, Buddy. Years later, Buddy is kidnapped. Brad sets off to find her.

But this isn’t a rescue mission. It’s a slow-motion moral implosion.

A Trail of Pain and Justification

Brad is a man defined by pain. His past is littered with scars: an abusive father, a dead sister (Lisa, the game’s namesake), years of numbing his trauma with a drug called Joy. Buddy represents not just a chance to save someone — she’s his only shot at redemption.

And he ruins everything.

As Brad’s journey unfolds, the player is forced to make decisions that steadily strip away his humanity. You can give up limbs, suffer permanent stat losses, and sacrifice party members. Often, the game doesn’t even ask — it forces you to lose. There are no hero moments. No clean wins. Just blood in the dirt and a sick feeling in your stomach.

The genius of Lisa is that it doesn’t just show moral decay — it makes you participate in it. You keep going, not because you believe in Brad, but because you’ve already gone too far to turn back. You’re not saving Buddy. You’re chasing an idea of her — an idea that exists entirely in Brad’s mind.

Addiction as Ethical Erosion

Brad is addicted to Joy, a drug that makes combat easier but has devastating consequences. The more he takes it, the closer he comes to turning into a Joy Mutant — a monstrous, deformed creature that’s lost all sense of self.

Eventually, that’s exactly what happens.

In many games, addiction is a status effect. In Lisa, it’s a moral rot. Each Joy dose you take is a small betrayal: of your body, your team, your mission, your self. But the world is cruel, and Joy makes it bearable — for a while. Sound familiar?

You can play clean. You can refuse the drug. But the game will punish you. Because pain is the price of integrity in Lisa, and integrity won’t save anyone.

What Philosophy Can’t Fix

You can try to analyse Lisa using ethical theory, but none of them fit quite right. That’s part of the point.

Deontology? Brad believes he has a duty to protect Buddy. But she didn’t ask for that. His version of protection is possessive, violent, and infantilizing. He’s not her father. He’s her warden.

Utilitarianism? The consequences of Brad’s journey are devastating. He kills indiscriminately. He dooms communities. His obsession poisons everything it touches. Even if his goal were noble (it’s not), the cost is unjustifiable.

Virtue Ethics? What virtue is there in a man who lies to himself as often as he lies to others? Brad’s actions are not courageous or compassionate — they’re desperate. He confuses clinging with caring, and the game never lets you forget it.

No philosophy offers him salvation. Because Brad isn’t a man trying to do good — he’s a man trying to feel less bad about what he’s already done.

Love and Control: The Same Fist

Brad loves Buddy. He also hides her, manipulates her, kills for her pushes here towards drug use (As eluded to in the sequel). He doesn’t want her to grow up. He wants her safe, untouched by the world — and untouched by choice.

And isn’t that the central tragedy?

Brad was a victim. But instead of breaking the cycle, he becomes another link in the chain. His protection is indistinguishable from violence. His love is a mask for control. He isn’t trying to save Buddy from the world. He’s trying to save himself through her.

The game’s refusal to show Buddy’s perspective until the very end is deliberate. You think you’re the protagonist. You think this is your story. But when you finally see her eyes, you realize: you were the villain the whole time.

No Clean Slates, No Happy Ends

There are no restarts in Lisa. No moral resets. Every loss is permanent. If a character dies, they’re gone. If you lose an arm, you’re weaker forever. This permanence is mechanical, but it’s also moral. The game is telling you: you don’t get to undo what you’ve done.

Brad’s final transformation into a Joy Mutant is a mercy. He becomes the thing he feared because he was already becoming it. You watch as what little is left of his mind dissolves. And when Buddy kills him — because she has to — the game doesn’t glorify it. It just ends. Quietly. Finally.

You were never her savior. You were her trauma.

A Wasteland with a Mirror

Lisa: The Painful doesn’t moralize. It doesn’t preach. It just hurts. But in that hurt, it forces you to confront things most games won’t touch:

What happens when love becomes ownership?

What are you willing to become for a goal you can't even justify?

When do your excuses stop being excuses?

Brad is a mirror. For every player who thinks they’re making the best of a bad situation. For every person who’s convinced themselves that suffering makes them righteous. Lisa says: no. Suffering just makes you hurt people harder.

Simply Put: Pain, and What Comes After

Lisa: The Painful is a game about damage — not just the kind done to you, but the kind you pass on. It's about how easily love becomes a leash, and how redemption is nothing but a fantasy we tell ourselves to keep moving.

There’s no right path in Lisa. Just the one you’ve already stumbled down, covered in blood, missing limbs, and pretending it’s noble. You didn’t save anyone. You just couldn’t let go.

In the end, maybe that’s the most painful part: Brad doesn’t fail because the world is cruel. He fails because he never learned how to stop being cruel himself.