What is Pre-Bunking: The Power of Framing Before the Facts

In today’s hyper-connected political landscape, where public perception often moves faster than the facts, the ability to frame a story before it fully emerges has become one of the most powerful tools in the political communicator’s arsenal. From campaign speeches to offhand social media comments, from state press briefings to viral misinformation, the battleground of modern politics is not just what happens, but how what happens is interpreted—and crucially, when that interpretation is shaped.

This is where pre-bunking comes in.

At its core, pre-bunking is the practice of pre-emptively shaping the meaning of potential information threats before they can take root. Unlike debunking, which responds to falsehoods after they spread, pre-bunking seeks to inoculate people against misinformation and damaging narratives ahead of time, subtly training audiences to be skeptical or dismissive of certain frames, terms, or actors. It is, in essence, psychological narrative control, and it works not by hiding the truth, but by defining the context in which the truth will be received.

While originally rooted in cognitive psychology and media studies, pre-bunking has evolved into a critical instrument of political strategy, especially in an era where facts are increasingly contested, and attention spans are limited. Political figures and regimes across the ideological spectrum have learned to weaponize language not only to communicate their message but to disarm opposing interpretations before they’re even made.

Consider a common political scenario: A damaging report is due to be released—an investigation, a leaked file, a court testimony. Rather than wait and respond to the fallout, a skilled political actor might go public days or weeks in advance, offering a seemingly offhand remark or partial disclosure that reinterprets or sanitizes the expected revelations. If the report later references ambiguous or charged terms “girls,” “poached,” “secret meeting” the audience has already been primed to read those terms through a harmless, often benign filter. The damage is not necessarily undone—but it is diluted, diverted, or deflected.

This strategy is not unique to any one country or ideology. U.S. President Donald Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin, Brazilian ex-leader Jair Bolsonaro, and the Chinese Communist Party have all used pre-bunking in different forms—redefining enemies, preempting evidence, shifting blame, and framing their own actions as misunderstood or manipulated by opponents. And it’s not limited to authoritarian regimes. In democratic societies, pre-bunking is often used by governments and public health agencies to protect the public from disinformation—such as falsehoods about vaccines, elections, or climate change.

In this guide, we will unpack the concept of pre-bunking from a political-psychological lens. We will trace its academic foundations, explore how it differs from debunking, and examine case studies from around the world. Along the way, we’ll also break down how it works, why it’s psychologically effective, and what ethical dilemmas it raises for modern democracies.

Understanding pre-bunking isn’t just about spotting political manipulation. It’s also about becoming a more informed consumer of information—someone who can pause when a story feels too neatly packaged, and ask: What interpretation am I being primed to accept?

Because in politics today, the first narrative often wins, not because it’s true, but because it got there first.

Theoretical Foundations — Inoculation, Persuasion, and the Psychology of Resistance

To understand how pre-bunking works and why it’s so effective, we need to look not to politics first, but to psychology, specifically the psychology of persuasion and resistance. The roots of pre-bunking lie in a theory developed in the early 1960s, long before social media or digital disinformation, but with remarkable relevance to today’s information environment.

This theory is known as inoculation theory, and it was first articulated by social psychologist William J. McGuire. McGuire was interested in a basic but puzzling question: Why are people so easily swayed by misinformation, and what could be done to make them more resistant to persuasion?

Drawing a metaphor from medicine, McGuire proposed that attitudes could be "vaccinated" in the same way bodies are vaccinated against viruses. Just as exposure to a weakened virus trains the immune system to fight off a stronger version later, exposing people to a mild attack on their beliefs—along with a refutation—can make them more resistant to future, stronger attacks.

The Structure of Inoculation Theory

McGuire’s framework consisted of two core components:

Threat – People must first perceive that their existing beliefs are vulnerable to challenge. This primes them to become cognitively engaged and defensive.

Refutational Preemption – This involves presenting a weakened version of a counterargument and then immediately refuting it. The audience practices resisting misinformation in a low-stakes environment, so when they later encounter stronger versions, they’re mentally prepared.

The idea caught on in fields like health communication, advertising, and education, where researchers tested how inoculation theory could be used to protect people against everything from peer pressure to smoking to cult recruitment. But it wasn’t until the rise of digital media and the epidemic of misinformation online that inoculation theory found a new frontier in political communication.

Pre-bunking as Inoculation Applied to Politics

Pre-bunking is essentially the political application of inoculation theory. It takes McGuire’s insights and deploys them not just to defend against belief change, but to actively shape how people interpret information before they even receive it.

Whereas traditional inoculation might say, “You may hear someone try to convince you that climate change is a hoax—here’s why they’re wrong,” pre-bunking says, “Watch out for people who call climate change a hoax; it’s a common tactic used by fossil fuel lobbyists to mislead the public.” The second message not only warns, but also discredits the future speaker and reframes the motive, planting doubt before the claim is even heard.

Psychologists like Sander van der Linden at the University of Cambridge and John Cook at George Mason University have helped modernize this theory for the digital age. Their research on “psychological inoculation” shows that people are significantly less likely to fall for misinformation when they are pre-exposed to the techniques of manipulation—such as fear-mongering, false experts, or conspiracy narratives. Their work has informed major pre-bunking interventions by tech companies like Google and YouTube, which have launched short videos and “info nudges” warning users about common misinformation tactics.

Why Pre-bunking Works So Well

Pre-bunking is powerful because it operates at the level of schema—the mental frameworks people use to understand and categorize information. Once a schema is activated (e.g., “This is likely misinformation”), new information is interpreted through that lens. By the time the actual narrative arrives, people are no longer neutral; they’re primed to view it as suspicious, exaggerated, or manipulative.

From a cognitive perspective, pre-bunking also taps into:

Confirmation bias – People tend to favor interpretations that align with their preexisting views. Pre-bunking subtly aligns new interpretations before facts challenge them.

Cognitive ease – If a narrative feels familiar or already explained, it’s easier to accept—and easier to dismiss contradictory evidence.

Availability heuristic – The first interpretation people hear tends to become the most accessible one in their memory.

This makes pre-bunking not just persuasive, but sticky—and that stickiness is what makes it so valuable to political actors seeking to shape how events, documents, or testimonies are understood before the public even sees them.

Pre-bunking vs. Debunking — Why Timing Is Everything

To understand the strategic power of pre-bunking, it's helpful to compare it with its more familiar cousin: debunking. Both are tools used to deal with misinformation, but they operate in fundamentally different ways, with very different levels of effectiveness.

Debunking happens after the damage is done. A false claim is already circulating, people may have already shared it, and some may even believe it. The task of the debunker is to chase down the lie, present facts, and try to change minds. This can work, but it’s an uphill battle. People often resist corrections, especially when misinformation aligns with their identity or worldview. Sometimes, attempts to debunk can even backfire, reinforcing the original false belief through repeated exposure.

Pre-bunking, on the other hand, takes place before the misinformation spreads. It anticipates the types of falsehoods or distorted narratives that are likely to emerge and arms people with the tools to recognize and resist them in advance. In this way, pre-bunking acts as a kind of mental filter. By the time people encounter the misleading content, they’re less likely to be swayed because they’ve already seen through the tactic.

Let’s consider a simple analogy. If debunking is like cleaning up a toxic spill, pre-bunking is like laying down protective barriers to prevent the spill from ever happening. Both are necessary at times, but prevention is always more efficient and often more effective than cleanup.

A Matter of Psychological Timing

The timing of these strategies is not just a tactical difference—it also affects how our brains process information. Research in cognitive psychology shows that first impressions matter. The first explanation or interpretation we hear about a topic tends to stick, even when it's later proven false. This is known as the continued influence effect.

In other words, the initial frame we use to understand a situation becomes a kind of mental default. If the first explanation is misinformation, and the correction comes later, our brains may continue to rely on the original false frame. Pre-bunking takes advantage of this by being the first to offer an explanation—ideally before the audience even knows there’s something to explain.

Why Debunking Often Fails

Even with strong evidence and good intentions, debunking runs into several cognitive obstacles:

Motivated reasoning: People tend to defend beliefs that align with their values, especially when those beliefs are under attack.

Backfire effect: In some cases, presenting a correction can make people double down on the false belief, especially if the correction feels confrontational.

Information lag: By the time misinformation is debunked, it may have already spread widely and become socially embedded.

This doesn’t mean debunking is useless—far from it. But it’s reactive, and often too late to stop the initial spread or belief formation. Pre-bunking, in contrast, is proactive and strategic. It gives people the ability to pause, reflect, and question before they absorb false or misleading claims.

Political Implications

In politics, the difference between pre-bunking and debunking isn’t just academic—it can shape public opinion, media narratives, and even election outcomes. Politicians who pre-bunk are not waiting to be accused or fact-checked. Instead, they define the terms of the conversation in advance, so that when potentially damaging information surfaces, it’s filtered through a pre-established lens.

For example, when a leader says, “You’ll hear a lot of fake news about me in the coming days,” they are not responding to criticism—they are pre-bunking it. By calling it “fake news” ahead of time, they are lowering the credibility of any future reports in the minds of their supporters, regardless of the truth.

This technique is especially effective in environments where media trust is already low. Once the public is primed to see opposing information as biased or malicious, even the most well-evidenced investigations can be brushed off as politically motivated.

Pre-bunking doesn't always replace debunking, but it often outperforms it. Its real power lies in its timing, subtlety, and psychological insight. The next section will explore exactly how it works—what tactics are used, and how they manipulate perception before facts even come into play.

Mechanisms of Pre-bunking — How It Works Before the Facts Arrive

To the casual observer, pre-bunking might look like a clever media comment or a spontaneous political jab. But beneath the surface, it’s built on a set of identifiable psychological and rhetorical tools. These are the mechanisms that allow a political actor, public figure, or institution to shape how audiences will interpret future information, often without the audience even realizing it.

Understanding these mechanisms is essential for recognizing pre-bunking when it’s happening—and for resisting its influence when it’s being used manipulatively.

1. Forewarning

The simplest and most foundational mechanism is forewarning. This is when a communicator alerts the audience that they may soon be exposed to misleading or harmful information. The warning often comes with subtle cues about who the source of that information will be and why they shouldn't be trusted.

For example, a politician might say, “The media is about to launch another smear campaign—don’t fall for it.” This primes the audience to doubt the credibility of any future criticism, even if it’s based on verified evidence. By placing the audience on guard, forewarning creates psychological resistance. People become more defensive, skeptical, and loyal to the person who "warned" them.

2. Refutational Preemption

This mechanism involves introducing a weakened version of an expected criticism or narrative and immediately offering a rebuttal. It's a mental rehearsal of how to reject that information when it later appears in full form.

Let’s say a leader knows an investigation will soon allege financial misconduct. They might say, “They’ll probably say I bent the rules on campaign donations—what they won’t tell you is that everyone does it, and I’ve always followed the law.” This sets up an alternative explanation before the actual evidence is released, reducing its future impact.

Refutational preemption is especially effective because it gives people a ready-made answer. When the real accusation arrives, the rebuttal has already been stored in the listener’s mind.

3. Framing Rehearsal

In political communication, framing is everything. It's not just what you say but how you say it—and which associations and values you attach to it. Framing rehearsal is the act of introducing key words or themes that will later shape the audience's interpretation of facts or events.

Consider the phrase “witch hunt.” When used repeatedly in advance of an investigation, it prepares audiences to view the process as illegitimate, biased, or politically motivated. Even if strong evidence is later revealed, the label has already shaped the lens through which people see it.

Framing rehearsal is particularly powerful when it taps into tribal or emotional language—words like “freedom,” “betrayal,” “patriot,” or “hoax” don’t just describe events; they instruct audiences how to feel about them.

4. Semantic Reframing

Semantic reframing involves redefining or neutralizing emotionally charged terms before the audience hears them in a potentially damaging context. This tactic is subtle but critical.

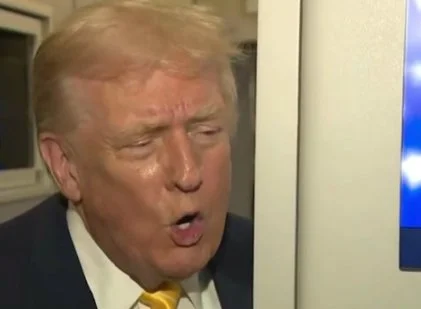

A striking example comes from Donald Trump, who in 2025 described Jeffrey Epstein as having “stolen girls from me,” then quickly clarified that he meant employees from the Mar-a-Lago spa. The use of the phrase “stole girls” anticipates potentially incriminating language in unreleased files. By preemptively attaching a harmless meaning to a charged term, Trump attempted to defuse its future rhetorical power.

This technique works by lowering the emotional stakes. If a phrase like “took girls to Mar-a-Lago” appears in documents later, supporters may recall the benign explanation first—creating doubt or minimizing outrage.

5. Emotional Positioning

Pre-bunking also relies heavily on emotional dynamics, particularly the use of victimhood and loyalty cues. A politician may frame themselves not as the source of controversy but as the target of unjust persecution. By doing so, they activate empathy and in-group loyalty.

This can be seen when leaders say things like, “They’re not just attacking me—they’re attacking all of us.” It encourages supporters to internalize the conflict, becoming emotionally invested in defending their leader against criticism, regardless of its merit.

When emotional positioning is used in advance of controversy, it creates a durable psychological shield. Supporters are no longer evaluating evidence rationally; they are protecting their identity and affiliations.

A Coordinated Strategy

These five mechanisms—forewarning, refutational preemption, framing rehearsal, semantic reframing, and emotional positioning—rarely appear in isolation. They are often used in combination, as part of a carefully constructed narrative strategy.

What makes pre-bunking so effective is that it doesn’t just tell people what to think. It subtly shapes how they think, what to question, and what to ignore. When done well, it feels natural, even obvious. But its true function is to shift the terrain of meaning before anyone else has a chance to speak.

In the next section, we’ll examine real-world examples of these mechanisms in action—across countries, leaders, and political systems—to see just how widespread and adaptable pre-bunking has become.

Case Studies — Pre-bunking in Practice Across Political Systems

While the theory of pre-bunking provides the framework, its real power is best understood by examining how it operates in actual political environments. Across democracies and authoritarian regimes alike, leaders have employed pre-bunking to get ahead of damaging revelations, shape the narrative landscape, and inoculate their base against future controversy.

In this section, we explore how five political actors or systems have used pre-bunking in practice, each revealing the flexibility and power of the tactic in different cultural and institutional contexts.

Donald Trump (United States): Reframing Scandal Before It Lands

Few modern political figures have employed pre-bunking more consistently or creatively than Donald Trump. From the 2016 campaign through his presidency and beyond, Trump has often relied on anticipatory framing, emotional positioning, and semantic reframing to reshape the battlefield of public perception before his opponents or investigators could define it.

Epstein Example (2025): “Stole Girls From Me” (Speculative Assessment)

In July 2025, Trump made headlines with a cryptic comment about his former associate and self-described best friend Jeffrey Epstein. Speaking to reporters, he claimed that Epstein “stole girls from me.” While the phrasing sparked immediate confusion and outrage, he quickly clarified that he was referring to Mar-a-Lago spa employees. To some, this sounded like a bizarre or even incriminating gaffe. But viewed through the lens of political psychology, it could be a textbook case of pre-bunking.

At the time, congressional efforts to release sealed Epstein-related documents were gaining momentum. These files were expected to include interviews, memos, and descriptions that could contain linguistically ambiguous phrases like “took girls,” “traded girls to,” or “introduced girls.” By introducing the term “stole girls” in advance and recontextualizing it as workplace drama not underage sex trafficking, Trump could have seeded a harmless interpretation of a potentially incriminating material.

If the files later include language that matches or resembles his phrasing, his supporters are already primed to dismiss the worst implications. This is semantic reframing combined with refutational pre-emption, functioning as a psychological defense mechanism ahead of time. This form of linguistic inoculation doesn’t just defend against scandal, it subtly reshapes public memory before it’s even formed.

“Witch Hunt” and “Fake News” as Framing Rehearsal

Earlier in his political career, Trump pioneered the use of framing rehearsal with terms like “witch hunt” and “fake news.” These weren’t just slogans; they were strategic inoculations. By repeating them over and over, he taught his supporters how to process any future investigation or media report. When the Mueller Report was released, or when impeachment hearings began, many in his base had already absorbed the belief that these were not neutral legal processes but politically motivated attacks.

This is the power of forewarning plus emotional positioning. Trump didn’t wait for accusations, he predicted them, framed them, and cast himself as a target of injustice before anyone else could define the stakes. We again are seeing this with the Epstein files, Trump has called it a Democrat hoax, that Obama and Hillary wrote them, that they don’t exist. Effectively covering throwing as much disinformation out there and knowing some of it will stick.

Vladimir Putin (Russia): Preemptive Justification of Aggression

In the lead-up to the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin gave a series of speeches in which he labeled Ukraine a “Nazi regime,” claimed that ethnic Russians were being oppressed, and warned that NATO was encroaching dangerously on Russia’s borders. These narratives were not reactive. They were pre-bunking messages designed to frame the coming war not as aggression, but as preemptive defense.

By the time tanks crossed the border, domestic audiences had already been conditioned to see the invasion as necessary, protective, and moral. Western media might present it as an unprovoked assault, but inside Russia, those interpretations had been pre-inoculated. Even international observers who had been exposed to months of Russian talking points began to repeat terms like “security concerns” and “NATO pressure.”

This is pre-bunking on a geopolitical scale. It combines forewarning, emotional positioning, and framing rehearsal to build domestic support and muddy the waters internationally.

Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil): Seeding Electoral Distrust Before the Vote

Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro began casting doubt on the country’s electoral system well before the 2022 presidential election took place. In speeches, social media posts, and interviews, he warned of fraud, accused the electoral court of bias, and hinted that the military might need to intervene to “protect democracy.”

This was not a response to actual fraud. It was a pre-bunking campaign aimed at undermining trust in the outcome before the first ballot was cast. If he lost, as he eventually did, his supporters had already been primed to view the result as illegitimate. If he won, the claims could be dismissed as merely cautionary.

This tactic mirrors what Trump attempted in the United States in 2020 and illustrates a broader trend among populist leaders: delegitimizing the system in advance to maintain power or justify resistance to its outcomes. The mechanism here is a blend of forewarning, emotional positioning, and refutational preemption, deployed to immunize a political base against democratic accountability.

Xi Jinping and the CCP (China): Pre-bunking Through Propaganda Infrastructure

In China, the state does not just pre-bunk through speeches or slogans. It does so through a deeply integrated propaganda system that anticipates foreign criticism and trains domestic audiences to see it as invalid or hostile.

When reports surface about human rights abuses in Xinjiang, censorship in Hong Kong, or threats to Taiwan, the Chinese Communist Party has often already prepared the public with narratives about “Western interference,” “anti-China bias,” and “foreign smear campaigns.” These narratives are built into textbooks, media programming, and public messaging—long before any particular incident occurs.

This represents institutional pre-bunking: a systematic inoculation effort that creates durable resistance to external information. The mechanisms include semantic reframing (e.g., calling concentration camps “vocational training centers”), emotional positioning (framing criticism as anti-Chinese racism), and framing rehearsal through patriotic messaging and media saturation.

Global Example: COVID-19 Pre-bunking Campaigns

Not all pre-bunking is manipulative. In fact, some of the most constructive uses of this strategy came during the COVID-19 pandemic, when public health experts and technology platforms worked together to inoculate people against vaccine misinformation.

Google and YouTube, in collaboration with behavioural scientists, launched short videos warning users about common manipulation tactics—such as fear-mongering, false authorities, or conspiracy theories. These clips didn’t debunk any single false claim. Instead, they explained how misinformation works, helping users build critical thinking habits.

This form of educational pre-bunking proved effective in reducing susceptibility to anti-vaccine rhetoric and illustrated the positive potential of these strategies when deployed transparently and ethically.

Pre-bunking Tactics in Political Communication — The Playbook of Anticipatory Narrative Control

While pre-bunking is grounded in psychological theory, its real power comes from how it’s applied through language, symbolism, and media strategy. Politicians and governments don’t need to use technical terms like “inoculation” or “semantic reframing” to wield this tool. Instead, they rely on a tactical playbook of rhetorical devices and messaging strategies designed to anticipate threats, neutralize opposition, and guide public perception before controversy fully takes shape.

These tactics are adaptable across ideological lines and political systems. Whether used to defend against scandal, delegitimize opposition, or maintain public confidence, pre-bunking techniques are remarkably consistent. Below, we break down the most common tactics used in political pre-bunking, alongside examples to illustrate how they work in practice.

1. Strategic Ambiguity

Strategic ambiguity involves deliberately vague language that can be interpreted in multiple ways. This allows political figures to introduce loaded terms while retaining plausible deniability. It also allows them to retroactively define what they “really meant” after the fact.

For example, when Trump said Epstein “stole girls from me,” the phrase was jarring and ambiguous. But when questioned, he softened its meaning to something far more mundane—employee poaching. This ambiguity allows for two interpretations to exist simultaneously: one that signals to loyalists or stirs controversy, and one that can be walked back when scrutiny increases.

In authoritarian regimes, this tactic is often used to veil threats or obscure intent—such as referencing “foreign elements” or “anti-national activities” without naming specifics. The goal is not clarity, but interpretive flexibility, which can be later leveraged depending on how events unfold.

2. Victim Repositioning

One of the most emotionally potent pre-bunking strategies is casting oneself as the victim in advance of criticism or scandal. This reframes anticipated accusations not as justice or truth-seeking, but as persecution, revenge, or political warfare.

By declaring, “They’re not just attacking me—they’re attacking you,” leaders invite the audience to internalize the conflict, creating emotional solidarity. This tactic encourages supporters to see criticism of the leader as a personal affront, making them more resistant to opposing narratives.

Vladimir Putin has often used this strategy by framing Western criticism of Russia as “anti-Russian hysteria,” while Bolsonaro repeatedly warned that the judiciary and electoral court were conspiring against him—not because of his behavior, but because he was an outsider challenging the system.

3. Attack Anticipation and Narrative Displacement

This tactic involves predicting or preempting an accusation, then redirecting attention by offering an alternative explanation or target. It functions like a form of mental misdirection.

For instance, a politician under investigation for financial misconduct might preemptively announce, “You’ll soon hear lies about me from corrupt insiders trying to distract from the real issue—our failing economy.” This plants doubt about the motive of future whistleblowers while also shifting the public focus to a more politically advantageous topic.

This tactic is especially effective when used in tandem with media saturation. By flooding the conversation with a different narrative—real or manufactured—a leader can crowd out damaging interpretations before they gain traction.

4. Co-opted Conspiracy Signaling

Rather than deny conspiracy theories outright, some political actors co-opt and reframe them, especially if they know the theory will emerge anyway. By embracing and repurposing a conspiracy before it spreads, they can redirect its energy in their favor.

This was seen in both Trump’s and Bolsonaro’s handling of election conspiracies. By voicing concerns about voting machines and fraud before the elections, they shaped future coverage and public discussion. If critics raised questions about vote legitimacy later, it no longer felt like a revelation—it felt like something already addressed.

This tactic taps into confirmation bias and plays particularly well on social media, where being “early” to a theory gives a leader narrative ownership, regardless of accuracy.

5. Control of Narrative Timing

One of the more subtle but effective tactics is timing the release of partial or softened information to set the interpretive frame before a more damaging version appears.

If a leak is expected or an investigation is nearing its conclusion, a political figure may release their own account of events—selective, emotionally framed, and incomplete—just before the official version becomes public. This tactic ensures that their version of the story is the first one people hear, giving it psychological priority.

In media psychology, this is tied to the primacy effect, which shows that early information tends to have a lasting influence on memory and belief, even when contradicted later.

6. Simplification and Repetition

Many pre-bunking strategies succeed because they rely on simple, repeatable language. Slogans like “fake news,” “deep state,” “witch hunt,” or “foreign interference” are easy to remember and emotionally charged. When repeated consistently, they create cognitive shortcuts that people rely on to interpret future events.

The more these slogans are used in advance of specific controversies, the more they shape perception when those controversies arise. Over time, they can become default interpretations that displace more complex, evidence-based narratives.

When These Tactics Combine

Most successful pre-bunking campaigns don’t rely on just one tactic. They combine multiple strategies—emotional appeals, ambiguity, repetition, and timing—into a cohesive messaging ecosystem. This makes them difficult to counter with facts alone, since the audience is already conditioned to distrust opposing information or view it as biased.

Understanding these tactics is the first step in defending against them—not only as citizens, but also as scholars, journalists, and educators. The next section explores how these strategies work at the psychological level and why they are so effective at bypassing rational scrutiny.

Psychological Mechanisms — Why Pre-bunking Bypasses Rational Resistance

To truly understand why pre-bunking is so effective, we have to look beyond language and politics and examine how the human brain processes information. Pre-bunking doesn’t work because it argues better; it works because it gets there first, quietly shaping mental shortcuts that influence how people perceive truth, trust, and intent.

This section breaks down the key psychological mechanisms that make pre-bunking so powerful—often more powerful than facts presented later.

1. The Primacy Effect

In cognitive psychology, the primacy effect refers to our tendency to better remember and be influenced by information we encounter first, even when subsequent information contradicts it. The first frame we hear often becomes the anchor for how we process all later messages.

Pre-bunking exploits this by being first to define the terms of a conversation. If a public figure is accused of corruption, but has already told their audience, “They’re going to make something up because I’m shaking up the system,” then that anticipatory frame can override later evidence. Even if the evidence is solid, it arrives after trust has already shifted.

In practical terms: the first story is not just remembered better—it frames everything that follows.

2. Cognitive Ease

We are all biased toward information that is easy to understand, familiar, and fluent. This is known as cognitive ease, and it plays a large role in why slogans, metaphors, and simple explanations are so persuasive.

Pre-bunking often uses repetitive, emotionally resonant language that is far easier to process than complex evidence or long-form journalism. Phrases like “witch hunt” or “foreign plot” are memorable and easily repeated. By the time a more nuanced or detailed version of the truth emerges, the audience has already internalized the easier narrative.

This is not a sign of irrationality—it’s a natural mental shortcut. But it also makes people vulnerable to persuasive messaging that arrives before critical thinking is engaged.

3. Confirmation Bias

Perhaps the most well-known psychological mechanism in political behavior, confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out, interpret, and remember information that confirms our preexisting beliefs, while ignoring or discrediting information that contradicts them.

Pre-bunking amplifies confirmation bias by preloading a favorable interpretation before any new information appears. If a political leader anticipates an accusation and claims, “It’s just the media twisting things again,” their supporters, already predisposed to distrust the media, are more likely to dismiss the accusation before even hearing it.

This makes pre-bunking an especially effective tool in polarized environments, where audiences are already sorted into ideological camps with sharply defined loyalties and enemies.

4. Psychological Inoculation

As discussed earlier, inoculation theory suggests that exposing people to a weakened version of a persuasive argument, along with a counter-argument, can build mental immunity against stronger forms of that argument in the future.

Modern pre-bunking applies this by showing people how they might be manipulated. For example, a video warning viewers about the tactic of using fake experts to push disinformation makes it more likely that those viewers will reject future messages that rely on those very tactics.

This is one of the more ethical and scientifically grounded uses of pre-bunking, especially when applied to health, climate, or civic education.

5. Affective Reasoning

Most political communication is not purely logical. It’s emotional. Pre-bunking often works because it creates an emotional filter through which people receive information. If someone is made to feel angry, fearful, or proud, they are less likely to evaluate new claims dispassionately.

When a leader casts themselves as a victim or frames criticism as a betrayal, they trigger an emotional response that makes their supporters defensive, loyal, and dismissive of outside input. This is known as affective reasoning, where feelings guide conclusions, not evidence.

Political actors use this tactic to insulate themselves from future scrutiny, knowing that once an emotional narrative is in place, factual contradictions will feel like personal attacks to their audience.

6. Memory Distortion and Narrative Stickiness

People do not recall raw facts. They remember stories—and particularly the first, simplest, and most emotionally satisfying versions of events. Once a story is told, it’s very difficult to dislodge. Even when people are told that part of the story was wrong, they often retain the emotional impact and basic structure.

This is why pre-bunking is so difficult to undo. A narrative that arrives early, hits emotional chords, and aligns with audience identity becomes cognitively “sticky.” Later corrections may be intellectually absorbed, but the original story still feels true.

In studies of misinformation, participants often continue to refer to debunked details if those details fit the story better than the truth.

Psychological Impact in Summary

| Mechanism | Effect on Audience |

|---|---|

| Primacy Effect | First exposure shapes long-term perception |

| Cognitive Ease | Simple explanations dominate complex truths |

| Confirmation Bias | Audience accepts what it already believes |

| Inoculation Theory | Weak exposure + rebuttal builds resistance |

| Affective Reasoning | Emotions override logic and critical thought |

| Memory Distortion | Initial stories linger, even when debunked |

Together, these mechanisms reveal why pre-bunking is not just a communication tool, but a cognitive strategy—one that can fortify beliefs and reshape perception without direct confrontation or censorship.

Ethical and Democratic Implications — When Pre-bunking Protects, and When It Distorts

Pre-bunking is a powerful tool. As we’ve seen, it can be used to guard the public against manipulation, disinformation, and harmful conspiracy theories. But it can also be used to manipulate perception, distort accountability, and pre-empt legitimate criticism. This dual nature presents a core ethical dilemma: When does protection become propaganda?

Understanding these implications is critical for anyone studying or practicing political communication in democratic contexts. While pre-bunking has legitimate uses, its misuse can erode public trust, disarm investigative journalism, and undermine democratic processes.

Pre-bunking as a Democratic Safeguard

At its best, pre-bunking can be a force for good. Public health agencies, educators, and civic institutions have increasingly used pre-bunking to inoculate citizens against deliberate deception. This has been particularly vital in moments of public crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when lives were at stake and misinformation moved faster than public messaging.

In these contexts, pre-bunking:

Empowers citizens by building resilience to misleading tactics

Encourages critical thinking and media literacy

Prevents harmful behavior before it begins (e.g., vaccine refusal or election interference)

Counters bad-faith actors without censorship, using transparency and foresight

For example, campaigns that explain how deepfakes or “fake experts” are used to mislead can reduce the likelihood that people will fall for such tactics. Here, the goal is not to control the narrative but to strengthen public reasoning before manipulation happens.

This form of pre-bunking aligns with democratic values—it builds a healthier information ecosystem rather than distorting it.

Pre-bunking as a Manipulative Shield

The ethical concern emerges when pre-bunking is used not to inform, but to protect power. When political figures preemptively dismiss valid scrutiny as “fake news” or reframe potentially incriminating language before facts are known, they are not defending the truth—they are obscuring it.

In these cases, pre-bunking becomes:

A shield against accountability, turning legitimate investigations into perceived attacks

A tool to discredit the press, the courts, or the opposition

A means of narrative control, used to condition supporters against future revelations

A way to blur the line between spin and reality, making the truth harder to discern

This is especially dangerous in democracies, where checks and balances depend on public access to facts, institutional credibility, and freedom of inquiry. If leaders use pre-bunking to undermine those pillars before they’re tested, they shift the balance of power from public institutions to personal charisma or media influence.

In authoritarian or hybrid regimes, pre-bunking may not just protect individual leaders but weaken civil society as a whole. When all criticism is framed in advance as “foreign interference” or “anti-national lies,” space for dissent and journalistic integrity begins to collapse.

The Risk of Cynicism and Distrust

Even in well-intentioned contexts, pre-bunking can have unintended side effects. If audiences begin to see all pre-bunking as strategic messaging rather than sincere guidance, it can lead to widespread cynicism and mistrust of all information—true or false.

This poses a real threat in a post-truth era, where many people already feel overwhelmed by conflicting narratives. If every message is seen as a pre-spin, public confidence in any authority—scientific, journalistic, or political—may continue to erode.

The challenge, then, is not just about whether pre-bunking is used, but how transparently and responsibly it is deployed.

Key Ethical Questions

Is the pre-bunking grounded in evidence, or is it speculative deflection?

Does it aim to inform or to insulate?

Is the audience empowered to think critically, or simply told what to believe?

Is it being used to protect the public, or to protect reputations?

Are dissenting voices still given space to challenge the narrative afterward?

When pre-bunking invites critical thinking and scrutiny, it strengthens democracy. When it shuts those doors in advance, it weakens it.

Democratic Resilience vs. Narrative Immunization

Ultimately, the ethical use of pre-bunking rests on one central distinction:

Democratic resilience means preparing people to resist falsehoods while preserving the possibility of new truths.

Narrative immunization, when abused, means making people resistant even to truth—if that truth contradicts a leader’s preferred story.

This is the line every communicator, policymaker, and citizen must learn to recognize.

In the final section of this guide, we’ll explore how these lessons can be applied through education, journalism, technology, and civic engagement, to strengthen information environments and build societies that are not only pre-bunked against lies, but resilient to manipulation of every kind.

Applications in Education, Media, and Policy: Turning Pre-bunking into Public Good

Understanding pre-bunking isn't just a matter of academic interest. In an era of increasing disinformation, political polarization, and algorithm-driven media, it is essential to consider how this knowledge can be used constructively. While the previous sections have shown how pre-bunking can be manipulated, this section focuses on how it can be applied ethically and transparently to strengthen democratic societies.

When used with care and accountability, pre-bunking can improve media literacy, enhance public trust, and protect vulnerable groups from targeted deception. The key is to shift its use from self-preservation to public empowerment.

1. In Education: Teaching Resilience Before Exposure

Education is one of the most effective domains for applying pre-bunking. When students learn how misinformation works before they encounter it, they are more likely to resist it. This approach moves beyond fact-checking and teaches process awareness: how to recognize emotional manipulation, identify logical fallacies, and understand the structure of propaganda.

Effective educational applications include:

Media literacy programs that train students to recognize rhetorical tactics used in political speech and advertising.

Simulations and games that expose players to weakened misinformation and teach them how to refute it.

Debriefing exercises where students analyze real-world cases of narrative framing and discuss alternative interpretations.

This kind of education doesn't tell students what to think. It shows them how thinking can be shaped, then equips them to ask better questions.

2. In Journalism and Media: Framing the Frame

News organizations can also incorporate pre-bunking techniques into their reporting. Rather than only reacting to misinformation after it spreads, journalists can anticipate how stories may be manipulated and inform audiences before it happens.

For example, when reporting on a controversial court case or public inquiry, a news outlet might:

Explain in advance what types of disinformation or spin have historically followed similar stories.

Publish a sidebar or video identifying common tactics, such as cherry-picking or misquoting.

Provide context that helps audiences interpret emotionally charged language or selectively released documents.

In doing so, journalists are not editorializing but clarifying the information environment. This helps protect audiences without compromising objectivity.

Some media outlets and fact-checkers already use these techniques, especially during election seasons. The next step is to standardize these approaches and collaborate with behavioral scientists to ensure they are effective and ethical.

3. In Public Policy: Pre-bunking as a Civic Tool

Governments and public institutions have a responsibility to maintain the integrity of civic discourse. Pre-bunking can be a proactive part of public policy, particularly when protecting the public from harmful misinformation in areas like public health, national security, or democratic participation.

Examples of policy-based pre-bunking include:

Election agencies warning voters about expected forms of misinformation before ballots are cast.

Health departments creating public campaigns about how anti-vaccine rhetoric operates, rather than waiting to correct false claims afterward.

Regulatory bodies working with social media platforms to identify patterns of coordinated manipulation and inform users early.

These interventions should be transparent, backed by evidence, and designed to strengthen public understanding rather than shut down dissent. Otherwise, they risk being perceived as propaganda, undermining their own goals.

4. In Technology: Designing for Early Intervention

Social media companies and search engines play a major role in shaping what people see first. That gives them a unique opportunity to apply pre-bunking strategies at scale, especially through design and algorithmic intervention.

Promising developments include:

Pre-bunking videos inserted into feeds that warn users about disinformation tactics (e.g., those produced by Google’s Jigsaw and Cambridge researchers).

“Accuracy nudges” that remind users to consider the reliability of a source before sharing.

Algorithmic adjustments that prioritize content providing context or warnings over sensational claims.

These efforts are still in early stages and must be carefully balanced with free speech principles. However, they represent a shift from reactive moderation to proactive digital literacy at the point of engagement.

5. Across Sectors: Coordinated Public Literacy Campaigns

The most effective applications of pre-bunking happen when educators, journalists, scientists, and policymakers work together. Coordinated campaigns can prepare the public in advance of vulnerable moments—elections, crises, policy rollouts—helping them process future information with a critical mindset.

Such campaigns should be:

Non-partisan and grounded in research.

Narrative-focused, showing not just facts, but how narratives are shaped.

Emotionally aware, understanding that belief and identity influence what people accept.

This is not just a defence against falsehoods. It is a strategy for cultivating a culture of reflection, where people are better equipped to navigate uncertainty and resist manipulation.

In the final section, we will bring together the major insights of this guide. We’ll reflect on what pre-bunking reveals about the psychology of belief and the politics of truth, and consider what it means to live in a world where the first story often wins.

Simply Put — We Live In a World Where the First Story Wins

Pre-bunking reveals something unsettling and powerful about modern political life: often, the truth does not win by being more accurate, more evidence-based, or more rational. It wins by being first, by being emotionally compelling, and by being anchored in a story the audience is ready to believe.

This is the world we live in now—a world where information is rapid, fragmented, and filtered through identities, algorithms, and biases. In that world, pre-bunking has become one of the most effective tools for shaping not only what people believe, but how they come to believe it.

We’ve seen how pre-bunking functions psychologically, from the primacy effect to emotional reasoning. We’ve explored how political figures, across ideologies and continents, use it to preempt scandal, control narratives, and protect their reputations. And we’ve considered how institutions, educators, and journalists can use pre-bunking more ethically, to prepare people; not with answers, but with better questions.

The takeaway is not that pre-bunking is inherently good or bad. Like all tools of influence, its moral weight depends on how it is used. When it is used to manipulate perception and insulate power from accountability, it undermines democratic values. But when used to educate, protect, and empower, it becomes a form of civic resilience—a defense not only against falsehoods, but against the erosion of trust itself.

Perhaps the most important lesson is this: our understanding of any event, claim, or controversy is never formed in a vacuum. It is shaped by the frames we are handed, the language we are taught to trust, and the emotional cues we absorb—often without realizing it.

Pre-bunking, when stripped down to its core, is about owning that space of interpretation first.

As students, educators, journalists, or engaged citizens, we must become more aware of this space. We must ask: Who is trying to define the story before it breaks? What assumptions are being planted early? What emotions are being stirred, and to what end?

To live in a free society is to take responsibility for how we interpret the world around us. Understanding pre-bunking is a step toward that responsibility. It reminds us that influence doesn't begin with the facts; it begins with the frame, and with those who choose it first.

References

Cook, J., Lewandowsky, S., & Ecker, U. K. H. (2020). The Debunking Handbook 2020.

Van der Linden, S. et al. (2020). Inoculating Against Fake News About COVID-19.

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework.

Explore your political beliefs with our neutral Political Leaning Quiz. Answer 10 easy questions to identify where you stand on the political spectrum, from Far Left to Far Right. Gain insights into your views and foster thoughtful political engagement. Start your journey of self-discovery today!