The Devolution of the “Fake News” Rhetoric

The Origins of a Weaponized Phrase

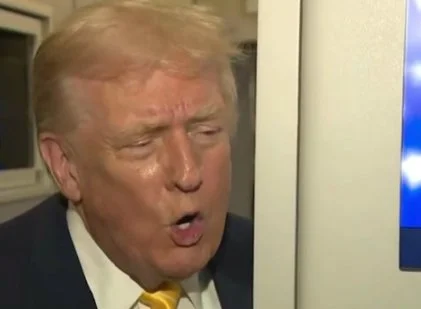

When Donald Trump first popularized the phrase “fake news” during his 2016 presidential campaign and subsequent presidency, it quickly became one of the most defining slogans of his political identity. The term initially appeared to describe false or misleading information, particularly on social media. However, Trump repurposed it to discredit mainstream journalism, especially any reporting that cast him or his administration in an unflattering light. What began as a label for misinformation has, over time, transformed into a rhetorical tool for delegitimizing the press and undermining the very concept of factual discourse.

The irony, of course, is that the label “fake news” applied more accurately to the disinformation circulating within Trump’s own political ecosystem than to the mainstream outlets he accused. Studies from organizations such as the Pew Research Center and Harvard’s Shorenstein Center have demonstrated that conservative media outlets and online networks aligned with Trump were disproportionately responsible for spreading unverified or false narratives during and after the 2016 election. Despite this, Trump successfully rebranded the term into a weapon against the press itself. Through repetition and strategic use in public appearances, he managed to associate “fake news” not with inaccuracy, but with any journalism that challenged him.

From Media Critique to Thought-Terminating Cliché

Over time, this rhetorical strategy has undergone a process of devolution. The phrase has lost any analytical meaning it once had and now functions primarily as a thought-terminating cliché. When confronted with a question that he finds inconvenient or critical, Trump’s instinctive response is not to address the content but to question the source. He often asks, “Who are you with?” and, upon hearing the name of an outlet he dislikes, simply responds with, “Fake news.” This pattern has become so familiar that it no longer raises eyebrows among his supporters. The exchange ends there: no explanation, no denial, and certainly no engagement with the issue at hand. The rhetorical move is simple but effective; it transforms a potential moment of accountability into a performance of defiance.

The use of “fake news” in this way serves as a form of linguistic control. It allows Trump and his supporters to reject uncomfortable truths without having to engage with them. By preemptively discrediting the media, Trump has cultivated an environment in which facts themselves become negotiable. Once a claim is labeled “fake,” it no longer requires rebuttal. It is simply dismissed, and the cognitive effort of evaluation is replaced by emotional allegiance. In this sense, “fake news” operates as a type of rhetorical inoculation. It shields adherents from exposure to conflicting information, maintaining ideological purity through selective disbelief.

The Erosion of Democratic Discourse

This phenomenon reveals a deeper shift in American political communication. Traditional democratic discourse relies on a shared commitment to facts, even when those facts are contested or interpreted differently. The erosion of that shared foundation has profound consequences. When political leaders and their supporters treat all information as partisan, truth becomes subordinate to loyalty. The public sphere ceases to function as a space for deliberation and instead becomes a battleground of competing realities.

The degradation of the term “fake news” also reflects broader trends in populist and authoritarian communication. Throughout history, authoritarian-leaning figures have sought to control information not only through censorship but through discrediting independent sources of truth. By undermining trust in the media, they weaken one of the primary checks on power. Trump’s rhetoric follows this pattern closely. His attacks on journalists as “enemies of the people” and his insistence that only he and his allies can be trusted echo the strategies used by leaders who blur the line between truth and propaganda.

Truth, Perception, and Power

The sociologist Hannah Arendt, in her work The Origins of Totalitarianism, argued that the destruction of factual truth is a key step in eroding democratic societies. When citizens can no longer agree on what is real, they become more susceptible to manipulation. Trump’s use of “fake news” exemplifies this process. It is not merely a political slogan but a mechanism for shaping perception. The goal is not to persuade through reasoned argument but to overwhelm through repetition and emotional resonance.

The decline in the meaning of “fake news” is also intertwined with changes in the media environment. The fragmentation of information sources has made it easier for political actors to construct parallel realities. Social media algorithms reinforce confirmation bias, and partisan media outlets cater to audiences who seek affirmation rather than information. In this context, Trump’s rhetoric did not create distrust in the media so much as it exploited and amplified it. His genius, if one can call it that, was to turn existing skepticism into a loyalty test. To reject “fake news” became synonymous with being a true supporter, while believing mainstream reports became a sign of betrayal.

A Phrase Emptied of Meaning

What is particularly striking about Trump’s continued use of the phrase is its emptiness. In its current form, “fake news” no longer refers to falsity, bias, or even journalism. It has become a placeholder for disapproval. Its meaning is entirely situational, dependent on who is speaking and what they wish to avoid. As a result, it functions perfectly as a thought-stopper. The psychological term “thought-terminating cliché,” introduced by psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton in his analysis of totalitarian thought control, describes phrases that are used to end debate and silence doubt. “Fake news” fits this description precisely. It ends inquiry by implying that further discussion is unnecessary, even dangerous.

The implications of this rhetorical decay extend beyond Trump himself. His followers have internalized the habit of labeling unwelcome information as fake, creating a self-reinforcing echo chamber. This dynamic is visible across social media, where accusations of “fake news” are used not to correct misinformation but to dismiss any source that contradicts partisan narratives. In this way, the phrase has become emblematic of a broader cultural shift in which emotional identity overrides empirical reasoning.

From Slogan to Symptom

Ultimately, the devolution of the “fake news” rhetoric reveals more than a change in language; it exposes a crisis in the way truth is negotiated in public life. The capacity for democratic discourse depends on a willingness to engage with opposing views and to be bound, however imperfectly, by shared facts. When political leaders and their followers replace engagement with dismissal, they erode the foundation of accountability that democracy requires. Trump’s casual use of “fake news” as a shield against scrutiny is not simply a quirk of style; it is a symptom of a deeper authoritarian instinct—the belief that power should define reality rather than be constrained by it.

The phrase that once signaled vigilance against misinformation has thus been hollowed out and repurposed into an instrument of denial. Its journey from media critique to ideological mantra charts the decline of honest discourse in American politics. To resist this devolution, citizens and journalists alike must insist on the difference between skepticism and cynicism, between critical inquiry and blind dismissal. The defense of truth in a democratic society begins not with slogans, but with the refusal to let them replace thought.

References

Arendt, H. (1951). The Origins of Totalitarianism. Schocken Books.

Lifton, R. J. (1961). Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism. W. W. Norton & Company.

Pew Research Center. (2019). U.S. Media Polarization and the 2020 Election: A Nation Divided.