Red vs. Blue: The Psychology Behind Political Affiliation in the US

Political affiliation is a profound aspect of human identity, influencing everything from voting behaviour to social interactions. In the United States, the dichotomy between "Red" (Republican) and "Blue" (Democratic) states epitomizes the political divide. Understanding the psychological underpinnings of political affiliation offers insights into why individuals gravitate towards particular political ideologies and how these affiliations shape their worldview. This essay explores the psychological factors influencing political affiliation, supported by peer-reviewed research, and examines how these factors contribute to the enduring division between Red and Blue.

Political affiliation is deeply rooted in psychological processes, including personality traits, cognitive styles, moral values, and social identity. By examining these factors, we can better understand the motivations behind individual political preferences and the broader societal implications of political polarization.

Personality Traits and Political Affiliation

The Big Five Personality Traits

Research indicates that the Big Five personality traits—openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—correlate with political preferences.

Openness to Experience:

Individuals high in openness tend to be more liberal, valuing creativity, novelty, and diversity. They are more likely to support progressive policies and social change (Carney et al., 2008).

Conscientiousness:

Conversely, those high in conscientiousness often lean conservative, valuing order, tradition, and stability. They tend to support policies that emphasize law and order and social cohesion (Mondak, 2010).

Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation

Two other personality dimensions, authoritarianism and social dominance orientation (SDO), significantly influence political affiliation.

Authoritarianism:

This trait involves a preference for order, obedience, and authority. Individuals high in authoritarianism are more likely to align with conservative ideologies, favouring strong leadership and strict social norms (Stenner, 2005).

Social Dominance Orientation:

SDO reflects a preference for hierarchical social structures. Those high in SDO are more likely to support conservative policies that maintain traditional social hierarchies and oppose egalitarian initiatives (Pratto et al., 1994).

Cognitive Styles and Political Affiliation

Need for Cognitive Closure

The need for cognitive closure (NFCC) is a cognitive style that reflects a desire for certainty and an aversion to ambiguity. High NFCC individuals prefer clear, unambiguous information and are more likely to endorse conservative ideologies, which often emphasize stability and predictability (Jost et al., 2003).

Cognitive Complexity

Cognitive complexity, the ability to understand and integrate multiple perspectives, is typically higher among liberals. Liberals tend to engage in more nuanced thinking and are more open to new experiences and perspectives, which aligns with their support for progressive and inclusive policies (Tetlock, 1983).

Moral Foundations Theory

Moral Foundations Theory, proposed by Haidt and colleagues, posits that political differences are rooted in distinct moral foundations.

Five Moral Foundations

Care/Harm:

Liberals prioritize the care foundation, emphasizing compassion and protection of the vulnerable.

Fairness/Cheating:

Both liberals and conservatives value fairness, but liberals focus more on equality, while conservatives emphasize proportionality.

Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Sanctity/Degradation:

Conservatives place greater importance on these foundations, valuing loyalty to in-groups, respect for authority, and purity, which aligns with their preference for tradition and social order (Haidt, 2012).

Moral Intuitions and Political Ideologies

These moral foundations shape political ideologies by influencing individuals' intuitive responses to social and political issues. For instance, a conservative's strong loyalty foundation may drive opposition to immigration policies perceived as threatening national cohesion, while a liberal's care foundation may drive support for refugee resettlement programs (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009).

Social Identity and Group Dynamics

Social Identity Theory

Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) suggests that individuals derive part of their identity from the social groups to which they belong. Political affiliation becomes a salient social identity, influencing behaviour and attitudes.

In-Group Favouritism and Out-Group Bias

People tend to favour members of their own political group (in-group) and exhibit bias against those of opposing groups (out-group). This dynamic is evident in political partisanship, where individuals align their beliefs and behaviours with their political group and view the opposition with suspicion or hostility (Huddy, Mason, & Aarøe, 2015).

The Role of Media and Social Networks

Media and social networks amplify these dynamics by creating echo chambers where individuals are exposed predominantly to in-group perspectives. This reinforcement strengthens political identities and polarizes attitudes, contributing to the Red vs. Blue divide (Sunstein, 2009).

Case Studies and Empirical Evidence

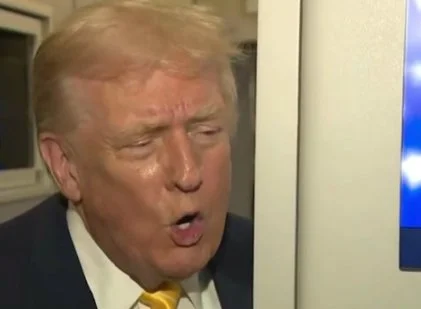

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election highlighted the stark psychological divides between Red and Blue voters. Research showed that Trump supporters scored higher on measures of authoritarianism and SDO, reflecting a preference for strong leadership and traditional social hierarchies. Conversely, Clinton supporters were higher in openness and cognitive complexity, aligning with liberal values of diversity and inclusiveness (MacWilliams, 2016).

Political Polarization and Moral Foundations

Studies on political polarization reveal that conservatives and liberals are increasingly viewing each other through a moral lens, with each side perceiving the other as morally deficient. This moral polarization exacerbates conflict and reduces the likelihood of bipartisan cooperation (Graham et al., 2011).

Broader Societal Implications

Impacts on Governance and Policy-Making

The psychological divide between Red and Blue has significant implications for governance and policy-making. Polarized political identities lead to gridlock, reducing the government's ability to pass legislation and address pressing issues. This division undermines democratic processes and erodes public trust in political institutions (McCarty, Poole, & Rosenthal, 2006).

Strategies for Bridging the Divide

Understanding the psychological roots of political affiliation can inform strategies to bridge the divide. Promoting intergroup contact, encouraging empathy, and fostering dialogue that acknowledges and respects different moral perspectives are potential approaches to reduce polarization and enhance mutual understanding (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006).

Simply Put

Political affiliation is a complex interplay of personality traits, cognitive styles, moral values, and social identity. These psychological factors shape individuals' political preferences and contribute to the enduring Red vs. Blue divide. By examining these underpinnings, we gain insights into the motivations behind political behaviour and the broader societal implications of political polarization. Addressing these divisions requires a nuanced understanding of the psychological dynamics at play and a commitment to fostering inclusive and respectful dialogue across the political spectrum.

References

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29(6), 807-840. The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. (apa.org)

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029-1046. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. (apa.org)

Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., & Haidt, J. (2011). The moral stereotypes of liberals and conservatives: Exaggeration of differences across the political spectrum. PLoS ONE, 7(12), e50092. The Moral Stereotypes of Liberals and Conservatives: Exaggeration of Differences across the Political Spectrum | PLOS ONE

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage. The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. (apa.org)

Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1-17. Expressive Partisanship: Campaign Involvement, Political Emotion, and Partisan Identity | American Political Science Review | Cambridge Core

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339-375. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. (apa.org)

MacWilliams, M. C. (2016). Who decides when the party doesn't? Authoritarian voters and the rise of Donald Trump. PS: Political Science & Politics, 49(4), 716-721. Who Decides When The Party Doesn’t? Authoritarian Voters and the Rise of Donald Trump | PS: Political Science & Politics | Cambridge Core

McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2006). Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. MIT Press. (PDF) Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches (researchgate.net)

Mondak, J. J. (2010). Personality and the foundations of political behavior. Cambridge University Press. Personality and the Foundations of Political Behavior (cambridge.org)

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751-783. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. (apa.org)

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741-763. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. (apa.org)

Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic. Cambridge University Press. The authoritarian dynamic. (apa.org)

Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Going to extremes: How like minds unite and divide. Oxford University Press. Going to Extremes - Hardcover - Cass R. Sunstein - Oxford University Press (oup.com)

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7-24). Nelson-Hall. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. (apa.org)

Tetlock, P. E. (1983). Cognitive style and political ideology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(1), 118-126. Cognitive style and political ideology. (apa.org)