The Painted World and the Price of Grief: Psychology at the End of Claire Obscur: Expedition 33

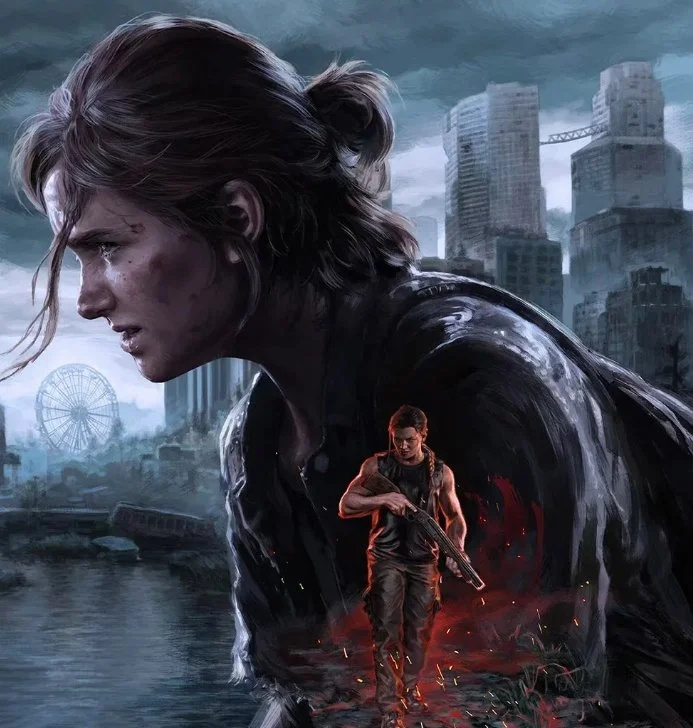

The curtain falls on Claire Obscur: Expedition 33 with a choice that feels less like a video game ending and more like a philosophical test. Do you stand with Maelle, preserving the painted city of Lumière and the lives within, though doing so slowly consumes her life and leaves Verso’s soul imprisoned? Or do you side with Verso, shattering the canvas that sustains the world, freeing him to rest but erasing an entire civilization in the process?

For many players, the decision is agonizing. It isn’t just about story preference; it’s about what you believe grief, truth, and compassion demand of us. The game forces us to confront the same questions that haunt real-world psychology and moral philosophy: is it better to protect ourselves with illusions, or to face the raw pain of reality? And do we owe moral obligations to lives that might themselves be illusions?

Foreshadowing the Final Choice

The moral tension at the heart of Claire Obscur: Expedition 33 isn’t confined to its ending. It’s seeded right from the beginning in the first argument between Gustave and Lune. While Maelle is still missing, Gustave urges Lune to break protocol and search for her immediately, while Lune insists on regrouping at the Tree as procedure demands.

At first, this reads as a simple clash of personalities — the impulsive protector versus the cautious rule follower. But in hindsight, it’s a microcosm of the game’s ultimate dilemma:

Gustave’s stance reflects the principles of care ethics—a moral philosophy emphasizing empathy, relational bonds, and responsiveness to the needs of others within their unique context. It holds that morally significant actions arise from emotional connections and an obligation to care for the vulnerable, often outweighing impersonal rules. His urgency—wanting to find Maelle at any cost—embodies this belief in prioritizing personal loyalty over protocol

Lune’s position, by contrast, aligns with deontological ethics (also known as duty-based ethics), which asserts that morality is rooted in adherence to universal rules or principles—regardless of emotional consequences. Under this view, moral actions are judged based on their alignment with duty, rather than their outcomes. Lune’s insistence on regrouping reflects a commitment to order and moral law, anticipating the game’s later demand for tough, principled choices.

This early conflict quietly trains the player in the moral grammar of the world. Before the climactic decision is ever presented, the game has already asked: should we bend the rules to protect someone we love, or uphold duty even when it feels heartless?

By embedding this tension in the very first chapter, Expedition 33 makes clear that the choice between Maelle and Verso isn’t a twist tacked on at the end — it’s the culmination of a moral struggle that has been there from the beginning. The entire journey is a rehearsal for that impossible question: what matters more — compassion or truth?

The Comfort of Illusion

Choosing Maelle is, psychologically speaking, a defense of denial. In grief research, this is not uncommon. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross famously described denial as the first stage of grief: the refusal to accept loss, insulating ourselves from its devastating impact. Modern psychologists, however, go further. They speak of continuing bonds theory—the idea that people often maintain symbolic ties to the dead through memories, dreams, or even imagined conversations.

Preserving Lumière is the grandest “continuing bond” imaginable. Rather than let Verso’s memory fade into finality, Maelle sustains a world where life, beauty, and relationships continue. To the player, it feels compassionate—like sparing loved ones (and ourselves) the brutality of absence.

But illusions come at a cost. Verso himself remains trapped, denied the dignity of rest. In moral terms, this exposes the tension between care ethics (which prioritize compassion and relational responsibility) and authenticity or deontological duty (which insist on respecting truth and the autonomy of the individual). To comfort many, Maelle sacrifices one—ironically the very person she sought to honor.

The Cold Honesty of Acceptance

Choosing Verso, by contrast, feels like stepping into the final stage of grief: acceptance. This is the painful recognition that denial cannot last forever. Therapists often stress that while denial and illusion may soothe in the short term, true healing requires confronting impermanence directly.

Destroying Lumière embodies that brutal honesty. The painted city collapses, and with it the lives of those who dwell inside. To players, this feels like cruelty: extinguishing joy for the sake of truth. But moral psychology reframes it differently. It is an act of existential authenticity, echoing thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard and Jean-Paul Sartre: to live truthfully is better than to live beautifully in a lie.

Still, authenticity here is costly. The “truth” brings devastation. If Lumière’s inhabitants are mere illusions, the act is tragic but justified: Verso’s soul is freed, and Maelle—and perhaps the player—accept reality at last. But if those inhabitants are truly sentient, then the choice becomes an ethical catastrophe.

The Sentience Problem

This is where the game’s ending becomes more than metaphor. What if the lives within Lumière are not just illusions? What if they feel, hope, and suffer?

If they are mere illusions, the decision is deontological: the duty is to honor Verso’s freedom, even if it destroys beauty. But if they are conscious, the dilemma transforms into a utilitarian nightmare. The lives of an entire city cannot be so easily dismissed. Preserving them, even at the cost of Verso’s suffering, becomes the more compassionate calculus.

This split isn’t confined to fantasy. As artificial intelligence grows more convincing, humanity faces a similar frontier. Today, shutting down an AI program feels like flipping off a light switch. Tomorrow, if AI convincingly demonstrates self-awareness or emotional depth, would switching it off be more like ending a life? Claire Obscur’s painted world eerily anticipates this question.

The philosopher John Searle’s “Chinese Room” argued that machines might only simulate understanding without ever truly knowing. But if that simulation is indistinguishable from sentience to us, should moral concern depend on hidden “realness,” or on the appearance of experience itself?

Grief as a Human Lens

What makes the ending of Claire Obscur so powerful is that it blends this technological thought experiment with the timeless psychology of grief.

Human beings have always oscillated between two impulses:

The comfort of illusion: We cling to photographs, rituals, even fantasies of loved ones to ease the pain of absence.

The cold honesty of reality: We eventually accept impermanence, even when doing so feels like betrayal.

Neither impulse is wrong. Both serve us in different ways. Illusion softens trauma; truth allows growth. The tragedy of the ending is that you cannot reconcile them. One path comforts the many but betrays the individual; the other honors the individual but annihilates the many.

Simply Put: Beyond the Canvas

In the end, Claire Obscur: Expedition 33 is not just a game about choices; it is a mirror held to our own psychological and moral struggles. The choice between Maelle and Verso is also the choice between memory and reality, compassion and truth, denial and acceptance.

And as AI and digital life grow more sophisticated, the painted world of Lumière feels less like fantasy and more like a rehearsal. One day we may have to decide whether to preserve or erase digital beings that seem as real as the city on the canvas.

Even the game’s title gestures toward this tension. Clair-obscur, the French term for “light-dark” (known in art as chiaroscuro), could just as well be read as “denial–acceptance.” And crucially, each can stand for either light or dark depending on perspective. For some, denial softens loss like a warm glow; for others, it is the shadow that keeps us from truth. Likewise, acceptance can be the searing clarity of daylight or the cold darkness of absence. The ambiguity of the term mirrors the ambiguity of the choice itself.

The genius of Claire Obscur is that it prepares us for this question not with lectures, but with tears. It forces us to feel the paradox of grief: that to heal we must sometimes destroy, and that to preserve we must sometimes deceive.

In that sense, the true subject of Claire Obscur is not Maelle or Verso at all. It is us—the players—forced to decide what we value most when beauty, truth, and life itself cannot coexist.

References

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. Macmillan.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford University Press.

Searle, J. R. (1980). Minds, brains, and programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(3), 417–424.