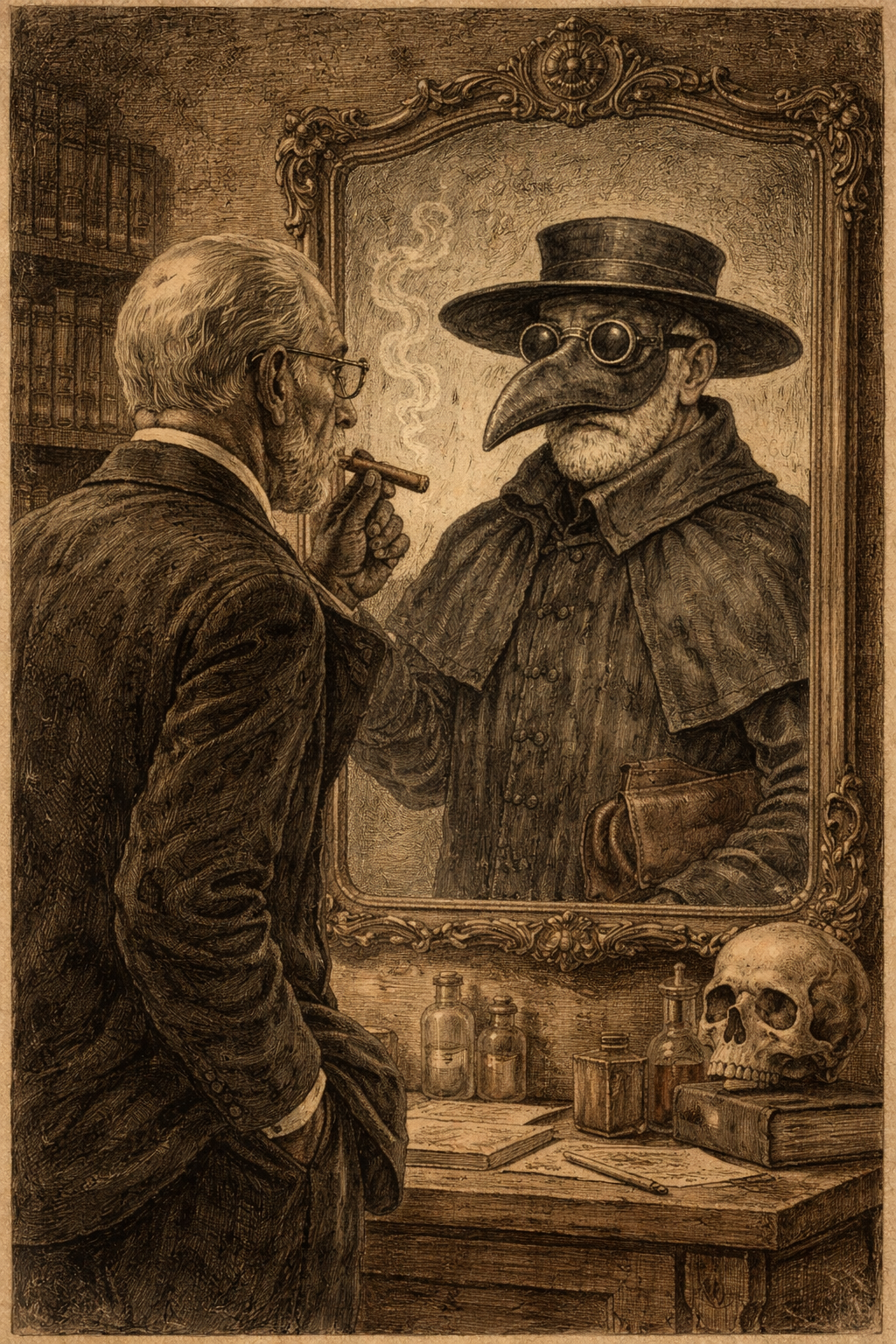

I Find Freud Humours: A Students Guide To How To Approach Freud

Freud is still taught everywhere, but rarely taught well. This guide uses the analogy of humours, leeches and bloodletting to show students how to read Freud critically: what to keep, what to discard, and why being wrong didn’t make him useless.

Few figures in psychology provoke as much confusion, reverence, irritation, and quiet dread as Sigmund Freud.

Students are rarely taught Freud as true anymore, but they are also rarely taught how to read him once he is no longer true. Instead, Freud is often presented in an awkward intellectual limbo: too important to ignore, too outdated to endorse, and too culturally embedded to dismiss. The result is a familiar undergraduate experience. Students memorise concepts no one fully believes, defend theories no one would publish today, and quietly wonder why this material has not been retired with polite academic honours.

This discomfort is not a failure of students. It is a failure of framing.

Freud occupies a strange historical position. He is not contemporary psychology, but neither is he ancient philosophy. He is foundational, but also deeply wrong. And crucially, many of his ideas are structured in a way that makes them unusually resistant to challenge. Freud does not merely offer explanations, he offers explanations that reinterpret disagreement as further evidence.

This is where a simple analogy becomes useful.

Freudian theory occupies a role in psychology strikingly similar to humourism in early medicine: the belief that health and illness were governed by imbalances in blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Humourism was not foolish. It was coherent, culturally dominant, and grounded in observation. It also explained almost everything, predicted very little, and could not be meaningfully falsified.

Seeing Freud through this lens does not trivialise him. It clarifies him.

This essay is not an attempt to debunk Freud, nor to rehabilitate him. It is a guide for students (and teachers) on how to approach Freud: how to read him historically, critically, and productively, without either swallowing the theory whole or discarding it in frustration.

Freud as pre-scientific psychology

To understand why the comparison to humours works, it helps to situate Freud properly in time.

Freud was working at the turn of the twentieth century. There were no brain scans, no randomised controlled trials, no statistical models of cognition. Psychology was still negotiating its identity, hovering somewhere between philosophy, neurology, and medicine. Freud was trying to build a comprehensive theory of the mind using clinical observation, introspection, and narrative case studies.

This is not unusual. Early sciences often begin with sweeping frameworks that explain a lot very confidently and test very little rigorously. In medicine, that framework was humourism, associated with figures such as Hippocrates and Galen. In psychology, Freud played a similar role.

Humourism worked by reducing illness to imbalance. Freud worked by reducing psychological distress to conflict; usually unconscious conflict, often sexual, frequently originating in childhood. Both systems offered:

grand explanatory reach

internal coherence

interpretive flexibility

cultural resonance

And both struggled with the same fundamental problem: they explained outcomes far better than they predicted them.

If a patient improved, the theory was confirmed.

If a patient deteriorated, the theory explained why.

If a patient objected, the theory explained that too.

This is not scientific robustness. It is theoretical insulation.

The unfalsifiability problem

One of the most enduring criticisms of Freudian theory comes from philosopher of science Karl Popper, who argued that psychoanalysis was not scientific because it was not falsifiable. A theory that explains every possible outcome, Popper argued, explains nothing in a scientific sense.

This is where Freud begins to look most like humours.

Consider the following pattern:

If a patient accepts the interpretation, it is insight

If they reject it, it is resistance

If they feel distressed, repression is working

If they feel fine, repression is working

There is no observation that decisively counts against the theory. Disagreement becomes data. Denial becomes diagnosis.

Humourism worked the same way. If bloodletting helped, excess blood had been removed. If it harmed, the imbalance was severe. If the patient protested, their humours were clearly disturbed.

The problem is not that these explanations are illogical. The problem is that they are too good at surviving contact with reality.

For students, this is a crucial lesson. A theory can feel convincing, elegant, and insightful while still being methodologically unsound. Freud is a masterclass in this distinction.

Interpretive authority and the expert problem

Both humourism and Freudian psychoanalysis place enormous power in the hands of the interpreter.

In humourism, the physician read the body.

In psychoanalysis, the analyst read the psyche.

In both cases, the patient’s own account was secondary. If it aligned with theory, it was accepted. If it contradicted theory, it was reinterpreted. The expert did not merely treat symptoms, they defined what symptoms meant.

This interpretive dominance has ethical consequences. Freud did not simply describe psychological processes; he claimed privileged access to their true meaning. Dreams were not what dreamers thought they were. Desires were not what people believed they wanted. Objections were not objections but defences.

Modern psychology is rightly wary of this posture. Evidence-based practice emphasises testable claims, client collaboration, and respect for subjective experience. Freud’s framework often did the opposite, subordinating lived experience to theoretical necessity.

Again, this does not make Freud uniquely dangerous. It makes him typical of pre-scientific systems that had not yet learned how to limit their own authority.

Where the analogy breaks down

At this point, it would be tempting (and wrong) to conclude that Freud should be discarded wholesale, like leeches and bloodletting.

This is where the humourism analogy must be handled carefully.

Humourism left almost nothing salvageable. Freud did.

Freud was wrong in useful ways.

While many of his specific claims have not survived empirical scrutiny, several of his core intuitions did. Freud did not invent these ideas fully formed, but he gave them psychological centrality:

that much mental processing is unconscious

that people defend against distressing thoughts and emotions

that early experiences shape later patterns of relating

that talking can be psychologically transformative

Modern psychology retained these ideas while stripping away Freud’s speculative machinery. Defence mechanisms were operationalised. Unconscious processes were studied experimentally. Developmental influence was reframed through attachment theory and learning models.

Freud named the terrain even when he mapped it incorrectly.

This is a crucial distinction for students. Freud is not valuable because he was right. He is valuable because he helped psychology ask the right kinds of questions before it had the tools to answer them properly.

What to treat like humours

Some Freudian concepts, however, belong firmly in the historical archive.

These include:

psychosexual stages as causal mechanisms

the universal Oedipus complex

dream symbols with fixed, universal meanings

libido as a unitary psychic energy

These ideas are best taught not as truths but as examples of how theory can overreach. They reveal more about the cultural assumptions of Freud’s time than about the workings of the human mind.

Teaching these concepts honestly as historically significant but empirically unsupported, does not weaken psychology education. It strengthens it. Students learn that theories age, authority decays, and confidence is not evidence.

Freud’s real contribution: method over model

If Freud’s theoretical model has largely collapsed, why does he remain so influential?

The answer lies not in his explanations, but in his method.

Freud took subjective experience seriously at a time when psychology was tempted to ignore it. He insisted that symptoms have meaning, that contradiction matters, and that people are not transparent to themselves. He treated speech not as noise but as data.

Modern therapies retained this relational depth while abandoning Freud’s metaphysics. Cognitive-behavioural, humanistic, and modern psychodynamic approaches all inherit something from Freud’s insistence that talking; structured, attentive, reflective talking can change people.

Freud’s mistake was not that he listened too closely. It was that he mistook interpretation for proof.

Why Freud lasted longer than humours

Another useful teaching question is why psychoanalysis lingered culturally long after humourism collapsed.

One answer is that psychology deals with meaning, identity, and narrative; domains that resist clean falsification. Medical theories die quickly when antibiotics work better. Psychological theories linger because they offer stories people recognise themselves in.

Freud provided a vocabulary for guilt, desire, shame, repression, and conflict. Even when empirically weak, these narratives felt subjectively true. Humourism explained illness. Freud explained people.

This is not a defence of Freud. It is a reminder that psychological theories operate simultaneously as science and culture. Their persistence tells us something about human needs, not just evidential strength.

Freud as a training ground for critical thinking

For students, the most important lesson Freud offers is not about the mind. It is about how to read influential theories once their authority has expired.

Freud should not be treated as doctrine. Nor should he be dismissed as an embarrassment. He should be treated as a primary source; like early evolutionary theory, pre-germ-theory medicine, or classical philosophy of mind.

Reading Freud critically trains students to:

distinguish explanation from prediction

identify unfalsifiable claims

recognise interpretive overreach

separate historical influence from empirical validity

In other words, Freud is a test case for intellectual maturity.

Simply Put

Freud is often taught as a problem to be endured rather than a text to be understood. The humourism comparison offers a way out of that trap.

Like humours, Freudian theory was:

a grand, totalising framework

built with limited empirical tools

internally coherent and culturally persuasive

resistant to falsification

And like humours, much of it failed once better methods arrived.

But Freud also left behind something more durable: a way of attending to the mind that modern psychology refined rather than rejected. He forced psychology to confront subjectivity, meaning, and conflict, even as his explanations for them collapsed.

For students, the lesson extends beyond Freud.

Psychology is a young science. Many of its most influential theories will age the way Freud has: partially right, structurally flawed, culturally revealing, and historically indispensable. Learning how to read Freud well is therefore training for something larger; learning how to engage with powerful ideas after they stop being true.

In that sense, Freud is humours for the psyche.

Wrong in mechanism.

Useful in history.

And dangerous only if mistaken for medicine.

That is not a failure of psychology.

It is how sciences grow up.

References

Popper, K. R. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. Routledge. (Original work published 1934)

Cramer, P. (2006). Protecting the self: Defense mechanisms in action. Guilford Press.