What is Cognitive Dissonance? Understanding the Conflict Within

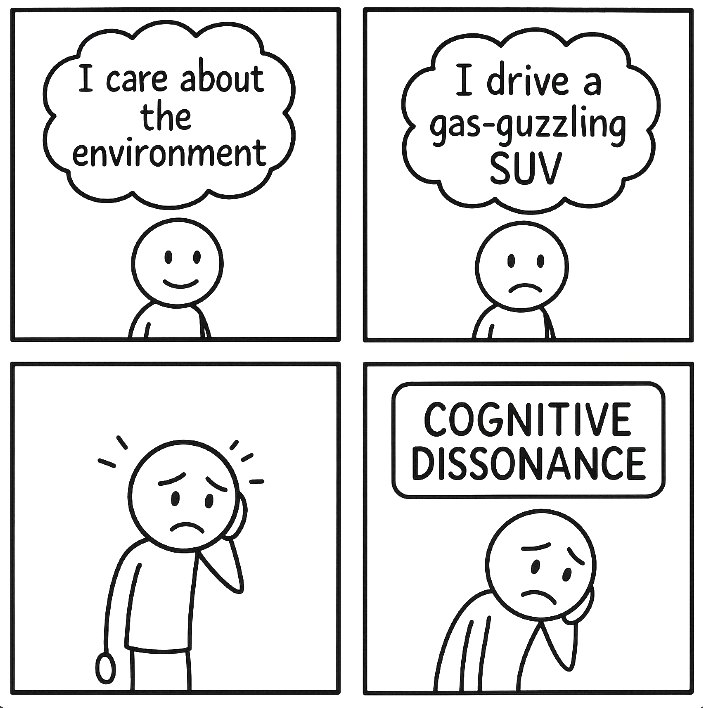

Cognitive dissonance explains what happens when our beliefs and behaviour don’t match — and why that mismatch feels so uncomfortable. In this guide, you’ll get a clear definition, everyday examples, classic studies, and key applications of cognitive dissonance theory for psychology essays and real life.

Cognitive dissonance is a psychological phenomenon characterized by the mental discomfort or tension a person experiences when holding two or more conflicting beliefs, values, or attitudes simultaneously. This discomfort often motivates individuals to resolve the inconsistency to restore cognitive harmony. Coined by social psychologist Leon Festinger in the 1950s, cognitive dissonance has since become a central concept in psychology, shedding light on human decision-making, behaviour, and the processes through which individuals reconcile conflicting thoughts.

Key Characteristics of Cognitive Dissonance

1. Conflict Between Cognitions

Cognitive dissonance arises when there is a contradiction between a person’s beliefs, values, or attitudes and their actions. For example:

Belief vs. Behaviour: A person values health but smokes cigarettes.

Belief vs. Belief: A person believes in honesty but also believes it’s acceptable to lie in certain situations.

2. Emotional Discomfort

The tension from cognitive dissonance often manifests as emotional discomfort, leading individuals to experience feelings such as guilt, shame, frustration, or regret.

3. Motivation to Resolve Dissonance

Humans have an innate desire to maintain consistency in their thoughts and actions. When cognitive dissonance occurs, this motivates individuals to:

Change their behaviour.

Alter their beliefs.

Rationalize or justify the inconsistency.

| Aspect | What It Means | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Mental discomfort caused by holding conflicting beliefs, values, or behaviours. | Valuing health but smoking cigarettes. |

| Source of Conflict | Mismatch between what we think/feel and what we do. | Caring about the environment but frequently using single-use plastics. |

| Emotional Experience | Feelings of guilt, shame, regret, or discomfort. | Feeling bad after gossiping about a close friend. |

| Common Reduction Strategies | Change behaviour, change beliefs, add new justifications, or minimise importance. | “It’s fine that I skipped the gym today, I’ve been really busy and I’ll go tomorrow.” |

| Classic Study | Festinger & Carlsmith (1959) showed people paid $1 to lie later changed their attitudes to reduce dissonance. | Participants told others a boring task was “interesting” and then convinced themselves it wasn’t so bad. |

Examples of Cognitive Dissonance in Everyday Life

Health Choices: A person who values fitness but skips exercising may feel guilty. To resolve the dissonance, they might justify their inaction by saying, “One day off won’t hurt.”

Purchasing Decisions: After buying an expensive gadget, a consumer might experience dissonance if they doubt its value. To justify the purchase, they might focus on the product’s advantages, downplaying any drawbacks.

Environmental Concerns: Someone who supports environmental sustainability but regularly uses single-use plastics might experience dissonance. They might resolve it by claiming their impact is negligible compared to larger systemic issues.

Interpersonal Relationships: A person who values loyalty but gossips about a close friend may experience discomfort. To ease the dissonance, they might rationalize their behaviour as constructive criticism.

Mechanisms for Resolving Cognitive Dissonance

To alleviate the discomfort caused by cognitive dissonance, individuals often employ one or more of the following strategies:

1. Change Behaviour

Aligning actions with beliefs is often the most direct method. For instance, a smoker might quit smoking to align with their belief in healthy living.

2. Change Cognition

Modifying beliefs or attitudes to match actions is another approach. A smoker might convince themselves that smoking isn’t as harmful as widely believed.

3. Add Cognitions

Introducing new thoughts to reconcile the inconsistency is common. For example, someone might justify eating unhealthy food by emphasizing that they exercise regularly.

4. Minimize Importance

Downplaying the significance of the conflict can also resolve dissonance. For instance, a person might consider their occasional indulgence in junk food as unimportant in the broader context of their generally healthy lifestyle.

Theoretical Foundations of Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance theory, introduced by Leon Festinger in his 1957 book A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, posits that humans strive for internal consistency. When inconsistency occurs, the resulting dissonance prompts efforts to restore balance. The theory is grounded in the following principles:

Cognition Relationships:

Cognitions can be consonant (aligned), dissonant (in conflict), or irrelevant to one another.

For example, “I value honesty” (cognition A) and “I lied” (cognition B) are dissonant.

Magnitude of Dissonance:

The degree of discomfort depends on the importance of the conflicting beliefs and the number of conflicting elements. More significant conflicts result in stronger dissonance.

Resolution Tendency:

The stronger the dissonance, the more motivated an individual is to resolve it.

Applications of Cognitive Dissonance

1. Marketing and Consumer Behaviour

Marketers often exploit cognitive dissonance to influence consumer decisions. For instance, offering post-purchase reassurances (e.g., testimonials, warranties) helps buyers justify their choices and reduce potential dissonance.

2. Health Interventions

Public health campaigns use dissonance to encourage behaviour change. Highlighting the inconsistency between unhealthy behaviours and personal health values can motivate individuals to adopt healthier habits.

3. Education

Cognitive dissonance is a powerful tool in learning. Teachers can challenge students’ preconceptions, creating dissonance that encourages critical thinking and deeper understanding.

4. Social Justice and Activism

Activists often highlight dissonance between societal values (e.g., equality) and existing practices (e.g., discrimination) to inspire change.

Critiques and Limitations of Cognitive Dissonance Theory

While widely accepted, cognitive dissonance theory has faced critiques:

Overemphasis on Rationalization: Some argue that the theory overstates individuals’ tendency to rationalize inconsistencies, ignoring other psychological mechanisms such as habit or emotional influences.

Cultural Bias: Critics note that cognitive dissonance theory may not fully account for cultural differences. In collectivist cultures, maintaining group harmony might override individual dissonance.

Measurement Challenges: Quantifying the subjective experience of dissonance remains a challenge, complicating empirical validation.

Cognitive Dissonance vs. Related Concepts

Cognitive Bias: While cognitive dissonance involves conflicting thoughts, cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking, such as confirmation bias or the availability heuristic.

Doublethink: George Orwell’s concept of doublethink refers to holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously without discomfort—a state that contrasts with the discomfort central to cognitive dissonance.

Simply Put

Cognitive dissonance is a fundamental aspect of human psychology that influences how we think, feel, and act. By understanding this phenomenon, individuals can become more self-aware, make informed decisions, and navigate the complexities of conflicting beliefs and values. Its widespread applicability, from personal growth to societal change, underscores its importance in both psychological theory and everyday life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a simple example of cognitive dissonance?

Cognitive dissonance occurs when your behaviour doesn’t match your beliefs — for example, valuing health but frequently eating fast food and feeling guilty about it.

How do people usually reduce cognitive dissonance?

People may change their behaviour, change their beliefs, add new justifications (“I’ll start next week”), or downplay the importance of the conflict.

Is cognitive dissonance good or bad?

It’s uncomfortable, but it can be useful. Dissonance often motivates people to reflect, change harmful behaviours, or align their actions more closely with their values.

How is cognitive dissonance used in marketing?

Marketers use it by reassuring customers after a purchase (e.g., reviews, guarantees) so buyers feel their decision was correct and reduce any post-purchase doubt.

References

Table of Contents

Cognitive Dissonance Game

Score: 0