The Paradox of Power: Why Strongman Leaders Make Fragile Societies

Why do rulers who present themselves as embodiments of strength so often preside over societies that seem increasingly fragile, dependent, and subdued? This apparent contradiction sits at the heart of authoritarianism. The strongman promises protection, stability, and national revival, yet the psychological and social dynamics of his rule often foster passivity, conformity, and learned helplessness among citizens. What begins as a display of power can ultimately weaken the very society it claims to fortify.

This paradox is not new. From classical political philosophy to modern psychology, scholars have observed how concentrated authority shapes the character of individuals and nations. Alexis de Tocqueville warned of "soft despotism," where paternalistic government reduces citizens to "timid animals" content with security but incapable of initiative. Later, psychologists like Erich Fromm and Martin Seligman explored how authoritarian environments cultivate dependency and helplessness, stunting autonomy and resilience. Contemporary research on obedience and conformity reinforces the same point: when individuals are consistently denied agency, they adapt by surrendering their strength to the authority above them.

Understanding this paradox is not only a matter of theory; it carries profound implications for political psychology and strategy. If authoritarian rule necessarily produces weaker citizens, then strongmen may build the conditions of their own eventual fragility. At the same time, the recognition of this paradox can be turned outward — used to frame narratives about the costs of authoritarianism, or to explore how societies might resist by reclaiming autonomy. This essay investigates the psychological underpinnings of the "strongman paradox," traces its historical manifestations, and reflects on its potential strategic and ethical implications.

Psychological Foundations

Authoritarianism is not only a political arrangement but also a psychological environment. The paradox of strong rulers producing weak citizens has roots in several key psychological theories and findings.

Authoritarian Personality Theory

In The Authoritarian Personality (Adorno et al., 1950), researchers argued that authoritarian systems thrive by shaping individuals who are rigidly obedient, deferential to authority, and hostile to dissent. Such citizens may appear disciplined, but their independence and moral reasoning are diminished. The “strength” of the leader thus correlates with the cultivated weakness of the populace.

Learned Helplessness

Martin Seligman’s experiments on dogs in the 1960s revealed that when living beings are consistently subjected to uncontrollable outcomes, they eventually cease trying to alter their circumstances — a state he termed learned helplessness. Applied to politics, authoritarian regimes that punish dissent and limit meaningful choice condition citizens to abandon initiative. Over time, people may no longer believe in their own efficacy, reinforcing dependence on the strongman.

Conformity and Obedience Research

The classic studies of Solomon Asch and Stanley Milgram demonstrate how social pressure and authority commands can override personal judgment. In Milgram’s obedience experiments, ordinary individuals were willing to inflict harm simply because an authority figure told them to. In authoritarian contexts, such pressures are magnified: dissent carries real risks, and compliance becomes habitual. Citizens adapt by aligning themselves with the strongman, but at the cost of weakening their critical faculties and moral courage.

Developmental Parallels

Research in developmental psychology shows that overly controlling parents can produce children who lack confidence, resilience, and decision-making skills. This "family system" analogy extends to authoritarian politics: the state acts as a domineering parent, while citizens regress into dependency. In both cases, strength at the top inhibits strength below.

Existential Security and Dependency

Terror Management Theory suggests that under conditions of fear and existential threat, individuals are drawn to strong leaders who promise order. Yet the stronger this reliance becomes, the more people outsource their coping strategies to authority. Citizens may feel secure in the short term but become psychologically less capable of self-reliance in the long term.

Taken together, these findings illustrate how authoritarian contexts cultivate populations that are obedient but disempowered, disciplined but fragile. The strongman’s power is thus reinforced by producing weakness in others — the essence of the paradox.

Historical and Political Examples

While the psychological mechanisms of authoritarianism are well documented in the laboratory, their most striking manifestations occur in political history. The paradox of strong leaders producing weak societies can be traced across regimes, past and present.

Stalin’s Soviet Union

Joseph Stalin presented himself as the embodiment of strength — the “man of steel.” Yet his purges systematically removed independent thinkers, military commanders, and innovative bureaucrats, replacing them with loyal but fearful subordinates. This climate of suspicion and obedience hollowed out the state’s institutional capacity. By the time of the German invasion in 1941, the Soviet military was initially hampered by a generation of officers too frightened to act without explicit approval. Stalin’s personal power was vast, but the society beneath him had been rendered brittle.

Mussolini’s Italy

Benito Mussolini styled himself as Il Duce, the decisive strongman who would revive Italian greatness. Yet his regime cultivated a political culture of ritualized conformity rather than genuine initiative. The fascist system demanded loyalty over competence, resulting in inefficient administration and poor military performance during World War II. Italy’s rapid collapse in 1943 reflected not only military weakness but also a citizenry habituated to dependency on the leader’s cult of personality.

Mao’s China during the Cultural Revolution

Mao Zedong sought to reassert control through the Cultural Revolution, mobilizing the Red Guards in fervent loyalty to his vision. While this secured Mao’s personal dominance, it devastated China’s intellectual and institutional strength. Educated professionals were denounced, schools and universities disrupted, and initiative punished. The result was a generation traumatized and disempowered, with the country’s social fabric severely weakened in the name of preserving Mao’s authority.

Contemporary Authoritarian Systems

Modern authoritarian regimes often exhibit similar dynamics. Leaders cultivate an image of strength while systematically undermining institutions that might generate independent capacity. Opposition parties, free media, and civic organizations are treated as threats rather than resources. This leaves the state dependent on the personal charisma and control of the leader — strong at the top, but weak beneath. The paradox is visible in how such regimes struggle with crises, from natural disasters to pandemics: the absence of empowered institutions and citizens hinders resilience.

The Fragility of Strength

These examples underscore the paradox: authoritarian strongmen may appear invincible, yet their very mode of governance hollows out the society’s ability to act without them. In eliminating alternative sources of strength, they create dependence, fragility, and long-term weakness. The leader’s strength thus becomes both the condition for and the symptom of collective weakness.

Strategic Implications

The paradox of strongmen producing weak citizens has significant implications for how we understand the stability and vulnerability of authoritarian regimes. While strongmen cultivate loyalty and dependence to consolidate power, these same dynamics create structural weaknesses that may be exploited — whether intentionally or simply as a byproduct of history.

Internal Vulnerabilities

By hollowing out institutions and discouraging initiative, authoritarian leaders leave their states less capable of responding to crises. Natural disasters, economic shocks, or military challenges reveal the absence of autonomous problem-solving capacity. In moments when the leader cannot directly control every outcome, weakness at the societal level becomes evident. This suggests that authoritarian strength is often a veneer, masking underlying fragility.

Narratives of Strength and Weakness

From a political psychology perspective, this paradox can shape narratives. Authoritarian regimes rely on myths of the strong leader saving the weak people; yet if citizens begin to see that their “protector” has in fact weakened them, the psychological foundation of obedience can erode. Framing authoritarianism not as a source of stability but as a producer of weakness undermines its legitimacy. This rhetorical inversion; exposing the “protector” as the “enfeebler” can be a powerful tool in reshaping public perception.

Resistance and Empowerment

Recognizing the paradox opens possibilities for resistance. If authoritarian systems thrive on dependency, then strategies that build citizen competence, confidence, and solidarity can undermine the regime’s psychological grip. Grassroots education, mutual aid, and civic organization strengthen the very qualities authoritarianism seeks to suppress. Empowerment becomes both a form of resistance and a pathway to resilience.

International and Strategic Dimensions

For outside observers, the paradox highlights both the appeal and the brittleness of authoritarian regimes. Their apparent stability can obscure vulnerabilities created by the suppression of autonomy and initiative. International actors often debate whether to emphasize these weaknesses in diplomacy, media, or policy. Even when not explicitly weaponized, awareness of the paradox informs strategies for engaging with authoritarian systems; from predicting their resilience to crises, to supporting societies as they rebuild autonomy after authoritarian collapse.

Ethical Tensions

Yet any discussion of the strategic use of this paradox must acknowledge ethical concerns. Deliberately exploiting psychological vulnerabilities shades into manipulation and disinformation. The challenge lies in distinguishing between propaganda and empowerment: are we manipulating populations for geopolitical advantage, or are we illuminating truths that help them reclaim autonomy? Ethical reflection is essential to prevent the paradox itself from becoming another instrument of control.

Ethical Considerations

Analyzing how the strongman paradox might be leveraged inevitably raises ethical questions. To study the psychological weaknesses of authoritarian systems is one thing; to contemplate their deliberate exploitation is another. Political psychology has long wrestled with the blurry line between education and manipulation, between empowerment and propaganda.

The Risk of Instrumentalization

When psychological insights are framed as strategic tools, they can easily slip into the logic of “psy-ops”, operations designed to shape perceptions and behaviour covertly. Such practices often disregard the autonomy of the very populations they claim to empower. In this sense, using the paradox as a weapon risks replicating the same dynamics of control and manipulation that characterize authoritarianism itself.

Empowerment vs. Manipulation

The ethical challenge lies in how the paradox is communicated. If the insight is shared transparently, for example, through education, scholarship, or journalism it can help citizens see how authoritarianism fosters dependency, thereby strengthening their agency. But if it is framed deceptively, with the aim of steering citizens’ thoughts without their consent, then the paradox is being turned into a mirror image of authoritarian control. The difference is between enabling independent judgment and orchestrating compliant responses.

Responsibility of Scholars and Practitioners

Political psychologists, historians, and strategists carry a responsibility to be mindful of how their work can be used. Scholarship on authoritarianism has often been applied in both emancipatory and manipulative ways. Reflecting on this dual-use potential is essential. A purely instrumental approach risks undermining the very values autonomy, resilience, critical agency; that the analysis seeks to defend.

Toward an Ethic of Illumination

An ethical way forward may lie in what could be called an “ethic of illumination.” Rather than treating the paradox as a weapon, scholars and communicators can present it as a lens: a way of clarifying what authoritarianism does to individuals and societies. The goal is not to impose choices but to restore the conditions in which people can make choices freely. If authoritarianism produces weakness, then the antidote is not counter-manipulation but the fostering of strength through awareness, dialogue, and self-determination.

Case Studies: Trump and Putin

The paradox of strongman politics becomes especially vivid when examined in contemporary contexts. Two of the most prominent figures of the early twenty-first century, Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, exemplify how leaders who claim exceptional strength generate dependency and fragility within their societies.

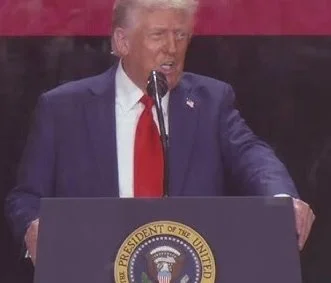

Donald Trump and the U.S.

Donald Trump rose to prominence on the promise of singular strength. His refrain “I alone can fix it” encapsulated a worldview in which America’s institutions were portrayed as incapable without his personal intervention. Yet his presidency often undermined the very institutional strength that sustains democratic resilience. Federal agencies were weakened by politicization, expertise was devalued in favor of loyalty, and public trust in electoral processes was deliberately eroded. In effect, Trump sought to position himself as indispensable by amplifying perceptions of institutional weakness.

This dynamic illustrates the paradox: Trump’s claim to strength rested on cultivating citizen dependency — on himself rather than on democratic institutions. The narrative of American weakness without Trump became both his justification for power and the mechanism by which citizens were discouraged from trusting their own collective capacities. Liberation, in this context, lies in reversing the narrative: reminding citizens that resilience comes from robust institutions and shared civic strength, not from dependency on a single leader.

Vladimir Putin and Russia

Vladimir Putin presents himself as the archetypal strongman: decisive, enduring, the guarantor of Russian greatness. Yet his system has systematically dismantled independent centers of strength. Media, civil society, and opposition politics have been constrained; economic modernization has been stunted by corruption and dependence on natural resource rents. The result is a society highly reliant on Putin’s personal legitimacy and increasingly fragile beneath the surface.

The Russian military campaign in Ukraine starkly revealed this paradox. Corruption hollowed out the armed forces, fear stifled initiative among officers, and the absence of independent institutions weakened the state’s ability to adapt. The leader who promised strength presided instead over brittle structures. For Russians, the recognition that Putin’s dominance has enfeebled rather than fortified their society could form the basis of a liberating realization: the supposed source of strength is in fact the architect of weakness.

Lessons from the Case Studies

Both Trump and Putin show how authoritarian leaders cultivate dependency by weakening the very institutions that empower citizens. Their strength is not additive but substitutive: they demand reliance on themselves by eroding confidence in collective systems. The strongman paradox thus manifests not as an abstract idea but as a lived political reality; one that exposes both the appeal and the fragility of such leadership.

Language and Reframing

Authoritarian leaders thrive not only on power but also on language. The very term strongman carries a built-in narrative advantage: it flatters the leader with an aura of strength and decisiveness. Such terms, when uncritically repeated, reinforce the mythology authoritarianism depends upon. To expose the paradox at the heart of strongman politics, language itself must be rethought. Reframing is both an academic exercise in discourse analysis and a political act of demystification.

The Problem with “Strongman”

To call a leader a “strongman” is to grant him the symbolism he craves. The word evokes toughness, vigor, and control. Yet as this essay has shown, authoritarian rule often functions by enfeebling citizens, stifling initiative, and hollowing out institutions. The strongman’s strength is therefore inseparable from the weakness he creates. Continuing to use the label uncritically risks perpetuating his preferred narrative.

Alternative Framings

Two possible reframings illustrate how language can puncture the illusion of invincibility:

“The Compensating Man”

This phrase highlights the psychological dimension of authoritarian posturing. The leader’s projection of strength is recast as overcompensation — a mask covering insecurity, weakness, or inadequacy. By reframing the strongman as the compensating man, his dominance becomes less a symbol of strength and more a symptom of fragility. The title itself implies that the very performance of power is proof of inner lack.“Hollow Power”

This framing shifts the focus from personality to structure. It suggests that the authoritarian’s power, though imposing on the surface, is empty within — built on fear, dependency, and institutional erosion. Hollow power conveys that what appears unshakable is in fact brittle, unable to withstand crisis or scrutiny. Unlike compensating man, which targets the leader’s persona, hollow power critiques the system he constructs.

The Stakes of Reframing

Language has material consequences. Reframing authoritarian leadership in terms that emphasize weakness rather than strength reshapes how both citizens and outside observers interpret political realities. Instead of admiring the leader’s dominance, the focus shifts to the costs of his rule: dependency, fragility, and decline. Academic discourse can illuminate this reframing, while public rhetoric can amplify it. Together, they weaken the symbolic foundations of authoritarianism without resorting to manipulation.

Reframing as Liberation

To rename the strongman is to challenge his myth. Whether as the compensating man or as the purveyor of hollow power, authoritarian leaders can be stripped of their symbolic armor. This is not simply a matter of semantics; it is a form of psychological liberation. If citizens come to see their ruler not as the source of strength but as the architect of weakness, then the first crack appears in the edifice of dependency. Language becomes both an analytic tool and a political act: it reclaims the power to define reality from the strongman himself.

Simply Put

The paradox of the strongman has echoed across history: leaders who claim to embody national strength often secure their rule by weakening others. Authoritarian systems, as psychology and history alike demonstrate, do not cultivate resilience, innovation, or independence; they cultivate obedience, conformity, and dependency. The strongman thrives not by empowering citizens but by enfeebling them. His strength is thus a mirror of their weakness — and in this sense, his power is always hollow.

The case studies of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin illustrate this paradox in practice. Trump’s refrain that “only I can fix it” positioned him as indispensable, but only because he sought to erode confidence in institutions and civic trust. Putin, meanwhile, styled himself as the guarantor of Russian greatness, yet decades of suppression and corruption left Russia brittle, revealed starkly in the strains of war. Both leaders demonstrate that the performance of strength often conceals a deeper pattern of fragility.

Language, too, plays a decisive role. To call such figures strongmen is to concede their central claim. Reframing them as compensating men or as wielders of hollow power punctures the myth of invincibility. These alternative framings remind us that authoritarian authority is not absolute but performative, not enduring but brittle. Words can liberate by shifting perception: when citizens see their ruler not as the source of strength but as the architect of weakness, dependency begins to crack.

This paradox is not merely descriptive; it is emancipatory. It shows that authoritarianism is unsustainable by design: in undermining citizens’ capacity, it hollows out its own foundations. Liberation begins with recognizing that what appears powerful is, in fact, precarious. The task of political psychology is not to manipulate but to illuminate — to show how strength imposed from above produces weakness below, and how reclaiming autonomy transforms weakness into shared resilience.

In the end, the true antidote to strongman politics is not another strongman but strong citizens. A society that refuses to surrender its agency cannot be infantilized. A people who see through hollow power cannot be ruled by it. And a public that names the compensating man for what he is begins the work of breaking the cycle of dependency. To expose the paradox is to open a path to empowerment — one where strength is no longer the monopoly of one man, but the collective inheritance of all.

References

Arendt, H. (1951). The Origins of Totalitarianism. Harcourt, Brace & Company.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness: On Depression, Development, and Death. W. H. Freeman.

Zimbardo, P. (2007). The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. Random House.

Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How Democracies Die. Crown Publishing.