The Language of “Play”: Infantilisation, Cognitive Dissonance, and the Culture of Epstein’s World

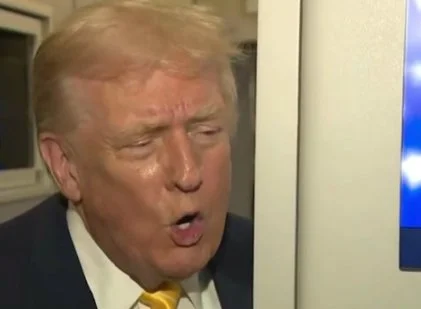

In recent years, the release of emails, notes, and testimonies relating to Jeffrey Epstein and his associates has drawn public attention not only to the factual record of abuse and exploitation but also to the peculiar language used by some of the most powerful men connected to him. Among these, Prince Andrew’s 2011 email to Epstein containing the line “we’ll play some more soon!!!” and Donald Trump’s birthday note to Epstein, framed as a dialogue and ending with “a pal is a wonderful thing. Happy Birthday – and may every day be another wonderful secret,” stand out for their tone and word choice. These are not simply odd turns of phrase. They reveal something deeper about the culture surrounding Epstein: a culture that appears to have encouraged powerful men to adopt an infantile or playful register, creating a parallel world in which abuse could be reframed as harmless “fun.”

This essay argues that the unusual word choices observed in such communications are not coincidental. They should be read as linguistic markers of an Epstein subculture, one that used infantilisation, secrecy, and playfulness as psychological mechanisms to resolve cognitive dissonance and sustain abuse. By adopting this register, men of high status could escape the moral and reputational constraints of their adult identities, indulging in transgression under the guise of “playtime.” The island, the mansions, and even the language all functioned as stages where dual identities could be maintained.

Disclaimer: This essay, presents an analysis and interpretation of language, communications, and publicly reported behaviour associated with Jeffrey Epstein and his associates. It is an analytical argument that applies psychological and sociological concepts (such as cognitive dissonance and psychological regression) to documented evidence to suggest the function of this specific linguistic register within Epstein's social orbit. The article does not make new factual claims regarding criminal conduct, but rather interprets established, publicly reported evidence (emails, court filings, media quotes). The analysis of language and psychology is interpretive and is offered to frame the underlying dynamics of the subculture. It does not constitute a legal finding or professional psychological diagnosis of the individuals involved.

The Odd Register of “Play”

The first striking element is the simple word “play” used by Prince Andrew. Among adults, “play” is rarely used to describe social interaction. One might say “let’s meet again,” “let’s catch up,” or “see you soon.” To describe future plans between two middle aged men as “play” is atypical, and even more unusual given the serious circumstances surrounding their relationship. Epstein was already a convicted sex offender by 2011, and Andrew had claimed to have severed ties with him months earlier. That the Duke of York instead wrote with cheerful enthusiasm about “playing some more soon” undermines his public claims and raises questions about the tone itself.

Similarly, Trump’s note to Epstein, written in the form of a stylised conversation between “Donald” and “Jeffrey,” leans heavily into coy, almost childlike phrasing. “Enigmas never age,” “a pal is a wonderful thing,” and “may every day be another wonderful secret” are not the expected words of a businessman and future president addressing a convicted offender. They evoke playacting, secrecy, and a kind of bratty affection that seems infantile when set against the seriousness of Epstein’s activities.

Both cases feature language that collapses the expected adult register into something closer to childish banter. This is important not because the words alone prove misconduct, but because the pattern suggests a cultural frame of interaction in Epstein’s world.

Infantilisation and Psychological Regression

Psychologists have long studied the way in which people use infantilisation or regression as coping mechanisms. Regression is a defense mechanism that allows adults to retreat into childlike behaviors when faced with stress or conflict. In Epstein’s orbit, however, regression appears not as a symptom but as a lure. The language of “play” and “secrets” provided an environment where men of immense public responsibility could step into an alternate persona, free from consequence.

Infantilisation offered relief from the demands of power. A prince, a president, or a billionaire carries the burden of constant scrutiny, duty, and image management. To slip into a private world where one could act like a mischievous child, indulging in “play” and sharing “secrets,” provided both escape and exhilaration. It was a form of regression that made the forbidden feel harmless.

Supporting Evidence

While the language of “play” and secrecy is most striking in communications such as Prince Andrew’s email and Donald Trump’s birthday note, similar linguistic patterns can be traced throughout Epstein’s wider world. Public records, court filings, and contemporaneous reporting all point to a subculture where euphemism, levity, and regression softened the perception of exploitation.

1. Euphemism around “massages” and “work”

Across police reports and indictments, the word “massage” functions as a consistent euphemism for sexual activity. The 2006 Palm Beach police investigation recorded more than thirty young women, some as young as fourteen, who were recruited to give “massages” that turned sexual. The 2019 federal indictment echoed the same phrasing, noting that Epstein “enticed and recruited minor girls to provide massages” that included sexual contact. Several witnesses stated they were told to bring “friends” to earn extra money, further disguising recruitment as a kind of casual job. These patterns reveal a linguistic code that minimized and normalized the abuse by dressing it in domestic and therapeutic language.

(Sources: Vox, July 2024; Palm Beach Police Report, 2006; SDNY Indictment, 2019.)

2. Email tone that minimizes wrongdoing

Unsealed 2015 emails between Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell show him encouraging her to act “as if you have done nothing wrong” and to “go outside, head high” after early public scrutiny. The tone is reassuring and almost paternal, treating criminal allegations as matters of confidence and attitude rather than guilt or harm. This rhetorical minimization fits the essay’s claim that Epstein’s language operated to dissolve moral friction, replacing accountability with breezy reassurance.

(Source: Global News, July 2020; The Times, July 2020.)

3. Maxwell’s own framing of “massages”

In her 2016 deposition, later unsealed by court order, Maxwell repeatedly referred to “massage training” and “massage rooms” while denying awareness of sexual conduct. Prosecutors and witnesses, however, described these same settings as the primary venues for abuse. The contest over the word “massage” demonstrates how language itself became a site of moral negotiation. By insisting on an innocent meaning, Maxwell preserved the linguistic veil that separated “work” from exploitation.

(Sources: Court deposition excerpts, Giuffre v. Maxwell 2016; Reuters, July 2020.)

4. Public register of levity and “adventure”

Before Epstein’s crimes were widely known, media profiles described his social life in strikingly playful terms. A 2002 New York Magazine article quoted Donald Trump calling Epstein “a terrific guy” and “a lot of fun to be with.” Bill Clinton was reported as praising his “keen sense of humor and taste for adventure.” Similarly, a 2003 Vanity Fair profile painted his gatherings as glamorous, filled with banter and youthful energy. Such portrayals reinforced an image of Epstein’s circle as witty and unserious, masking predation under the language of charm and amusement.

(Sources: New York Magazine, 2002; Vanity Fair, 2003.)

5. Juvenile cues in elite social settings

Accounts of Epstein’s salons and science dinners describe a strangely casual, at times juvenile atmosphere. Young women served as assistants or companions while elite guests discussed intellectual projects. Journalists and attendees have noted the dissonance between the seriousness of the company and the “college dorm” ambiance of the gatherings, complete with joking and flirtation. The combination of power and play reinforced the dynamic this essay identifies: an infantilised space where adult men could act without consequence.

(Source: The Guardian, August 2019.)

6. Patterns visible across unsealed documents

The large collection of unsealed “Epstein Files” confirms these linguistic habits across thousands of pages of depositions, police reports, and emails. The repetition of terms such as “massages,” “work at his home,” “appointments,” and “fun” provides a corpus-level view of how abuse was obscured by euphemism and familiarity. This cumulative evidence demonstrates that the language of regression and secrecy was not incidental but structural. It allowed the network to sustain its operations under a veneer of normality.

(Sources: U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York filings; Newsweek, January 2024.)

Integrative Reflection

Taken together, these materials substantiate the claim that Epstein’s world developed a distinctive linguistic culture. Words such as massage, fun, and adventure blurred the boundaries between abuse and amusement, while Maxwell’s own language extended this minimization into official testimony. The tone of reassurance, secrecy, and levity found across the communications created an alternate moral register—a world in which power could indulge itself under the guise of play.

Secrecy and the Language of Complicity

The motif of secrecy runs alongside the theme of play. Trump’s note, ending with the wish that “every day be another wonderful secret,” exemplifies this. Secrets are normally associated with intimacy, complicity, and exclusivity. To be entrusted with a secret is to be “inside,” a member of the inner circle. Epstein’s world appears to have operated through this structure of secrecy, offering participants a sense of being part of something hidden and special.

Language played a key role in this dynamic. Referring to encounters as “play” or “secrets” created a linguistic bubble where transgression could be reinterpreted. The words softened the reality. Abuse could be cast as “fun.” Affairs could be reimagined as “games.” Encounters with women, including those underage, could be framed not as crimes but as “playtime.” This reframing made it psychologically easier for participants to reconcile their actions with their public identities.

Cognitive Dissonance and Dual Identity

Here the concept of cognitive dissonance becomes central. Cognitive dissonance is the psychological discomfort that arises when one holds two conflicting beliefs or behaviors. For men like Andrew or Trump, the conflict would have been acute. Publicly they were figures of status and responsibility. Privately they were associating with a convicted sex offender whose world included the abuse of minors.

The linguistic register of play and secrecy provided a solution. By adopting this tone, they could compartmentalise their identities. In the public sphere, they were dignified leaders. In the private Epstein sphere, they were playful, mischievous, even bratty children. The two worlds were held apart by language, space, and ritual.

This dual identity is mirrored in the physical spaces Epstein controlled. His island, his mansions, and his jets functioned as stages where the “playtime” persona could emerge. Geographically and socially isolated, these locations reinforced the sense that what happened there was not real life. The island in particular became symbolic of this alternate world, a place outside normal moral and legal boundaries.

The Subculture of Mimicry

Another explanation for the shared oddness of the language is mimicry. Social psychology shows that people unconsciously adopt the speech patterns and behaviors of those around them as a way of showing belonging. Epstein appears to have cultivated a specific register in his world, one that combined secrecy, play, and childlike affect. His guests, in turn, adopted this register as part of their participation.

Over time, this created a subcultural lexicon. To be “in” Epstein’s world was to speak in its language. From the outside, the register seems bizarre. From the inside, it was a marker of belonging. Just as groups develop in-jokes, accents, or shared slang, Epstein’s circle developed a way of speaking that signaled membership and complicity.

The Power Structure of Infantilisation

There is also an unsettling inversion of power at work. While the men involved were some of the most powerful figures in the world, in Epstein’s orbit they took on the role of children. Epstein himself played the role of provider or parent, supplying the environment, the “toys,” and the rules of the game. This inversion may have been part of the appeal. To act as a submissive or bratty child allowed men otherwise constrained by duty to indulge in irresponsibility.

In this sense, infantilisation was not merely a linguistic quirk but a social structure. Epstein’s allure lay not just in access to women, but in offering a cultural stage where the powerful could shed their power and act without consequence. The word “play” thus captures more than a casual plan to meet again. It encodes the entire psychology of the environment.

Why the Language Matters

Critics may argue that words alone cannot prove misconduct. This is true. But in the context of Epstein’s network, words are not neutral. They are part of the mechanism by which abuse was normalized and sustained. When a prince speaks of “playing some more” with a convicted offender, or a president writes of “wonderful secrets,” the language itself is evidence of the subculture in which they were participating.

Language frames perception. By describing encounters as “play” or “secrets,” participants reframed transgression into harmless fun. This is how cognitive dissonance was managed and how reputationally constrained men could reconcile their behavior with their public lives.

Simply put

The peculiar word choices observed in communications between Epstein and figures like Prince Andrew and Donald Trump are not incidental. They reveal a cultural and psychological structure that underpinned Epstein’s world. Infantilisation, secrecy, and playfulness provided both allure and cover. They allowed powerful men to regress into childlike roles, to indulge in transgression without confronting it as crime, and to maintain a dual identity that separated their public responsibilities from their private indulgences.

Epstein’s power was not simply in money or access. It lay in creating a subculture where language, space, and behavior all worked together to suspend reality. The island, the mansions, the flights, and the words themselves constituted a stage on which abuse could be reframed as “harmless playtime.”

Understanding this culture is crucial not only for interpreting past events but for recognizing how similar dynamics may emerge in other elite networks. When infantilisation and secrecy become normalized registers of interaction, they should be treated as warning signs. They are not quirks. They are symptoms of a deeper system that enables abuse.