Has the UK Just Legitimised Trump’s Trade War?

How Britain became the first to fold and what it reveals about power, psychology, and strategic risk in the new global order.

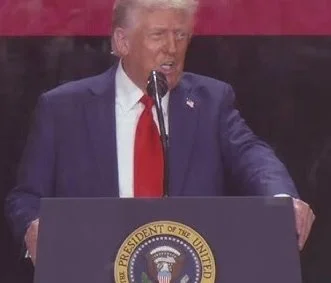

On 8 May 2025, the United Kingdom became the first country to strike a bilateral trade deal with the United States following President Trump’s so-called "Liberation Day" tariffs. Framed by Trump as a patriotic act of economic self-defence, the tariffs imposed a sweeping 10% import duty on all foreign goods, with threats of even higher penalties for key sectors like autos and steel. While the European Union, Canada, and Japan denounced the move as economic coercion, Britain moved quickly to negotiate.

The resulting agreement has been spun by both governments as a win: Trump trumpeted new market access for American beef, ethanol, and aerospace goods, while Prime Minister Keir Starmer celebrated the safeguarding of British car and steel jobs. But beneath the self-congratulatory headlines lies a deeper question: by being the first to cut a deal under Trump's coercive framework, has the UK legitimised a dangerous new era of protectionist power politics?

This op-ed argues yes, and not just in economic terms. Britain’s early compliance carries psychological, diplomatic, and strategic consequences that risk undermining collective resistance to trade bullying, emboldening unilateralism, and weakening the rules-based order the UK has long claimed to champion.

Disclaimer: The analysis below is not an economic or legal assessment, but a strategic and psychological interpretation of publicly observable decisions and patterns in trade diplomacy. Drawing from political psychology, negotiation theory, and framing research, this essay explores the underlying dynamics of the UK’s response to U.S. tariff policy and the broader implications for international norms. As with all behavioural analysis of political action, interpretations are subject to limitations and should be considered as one perspective among many.

Key Points

The UK became the first country to strike a trade agreement with the United States following President Trump’s imposition of sweeping “Liberation Day” tariffs in April 2025.

The U.S.-UK Reach Historic Trade Deal has been described by both governments as a landmark economic deal with the United States that saves thousands of jobs for British car makers and the steel industry.

While the deal reduces U.S. auto import tariffs from 27.5% to 10% on the first 100,000 British vehicles and eliminates tariffs on UK steel and aluminium, it preserves Trump's coercive tariff framework.

The UK agreed to quotas and reciprocal tariff structures, along with greater market access for U.S. agricultural and industrial exports.

Critics argue the UK’s early compliance legitimises Trump’s protectionist strategy, fracturing multilateral resistance from the EU, Canada, and Japan.

From a political psychology perspective, the UK’s move may signal a dangerous precedent: that coercive economic power can dictate global trade terms.

Though the deal offers tactical benefits for key UK sectors, it risks undermining the broader principles of rules-based international trade and coordinated democratic resistance to economic intimidation.

Frame Control and Economic Nationalism

Trump’s announcement of the Liberation Day tariffs was a masterclass in political psychology. By framing the policy as a form of "economic independence," he set the terms of debate before negotiations began. The language invoked wartime heroism, patriotic duty, and industrial revival. According to behavioural economists, framing effects can profoundly shape how people interpret options. In this case, Trump made it politically costly for other governments to appear opposed to what he portrayed as economic justice.

He coupled that framing with dominance signalling, which is the use of economic power to coerce compliance. The tariffs were not a negotiation starting point; they were punishment, imposed unilaterally, with the offer of reprieve only for those who accepted Trump’s rules. This created a power asymmetry: any country entering talks was doing so under duress.

Britain’s choice to be the first through the door cannot be separated from this framing. The urgency to avoid sectoral damage was real. UK steel producers faced tariffs of 25%, and automakers were staring down 27.5% U.S. import duties. But in reacting swiftly and separately, Britain did not just act pragmatically, it helped validate Trump’s framing.

The First-Mover Disadvantage

In negotiation theory, being first can sometimes be an advantage, but only if one controls the terms. Here, the UK entered talks not from a position of strength, but vulnerability. It signalled its willingness to deal quickly, revealing its strategic priorities (steel, cars, pharma), and thus, its weaknesses.

The deal’s terms reflect that imbalance. The U.S. agreed to lower auto tariffs for up to 100,000 UK vehicles annually, after which the 25% rate kicks back in. British steel and aluminium exports were granted full tariff relief, but in return, the UK reduced or eliminated tariffs on a wide array of U.S. goods, from ethanol to aerospace parts. Trump secured a key political win: proof that his tariffs work.

By moving first, the UK allowed itself to be used as precedent. Trump immediately positioned the UK as a model for others to follow. The message to Canada, Japan, the EU was clear: bend, and you can be next.

Compliance as Legitimisation

Political legitimacy isn’t just earned through ideals; it’s often constructed through compliance. When a country accepts the terms of a coercive framework, it lends that framework credibility. Britain’s deal signals to other governments that Trump’s unilateralism is not only survivable, but profitable.

This is dangerous. One of the key principles of post-WWII trade architecture has been that disputes are settled multilaterally. Trump has long rejected this, preferring bilateral deals where the larger power dictates terms. Britain, in seeking relief, has become an unwitting validator of that vision.

The UK government insists it protected its food standards and retained its digital services tax, and that may be true. But the broader reality is this: the UK agreed to a framework based on coercive leverage, quota-based access, and reciprocal tariff baselines. That is not rules-based trade. It is conditional appeasement.

Strategic Costs Beyond the Deal

Economically, the UK wins some relief for key sectors, but with caveats. The auto quota is small relative to long-term growth projections. The tariff reductions on U.S. goods will expose some British producers to new competition. Most concerningly, the 10% baseline tariff remains in place, setting a new norm for how the U.S. might treat even its closest allies.

Diplomatically, the UK’s decision fractures what could have been a coordinated front. While the EU prepares WTO challenges and Canadas active retaliation, Britain has made separate peace. That undermines the collective leverage of Western allies and emboldens Trump’s divide-and-conquer approach.

Psychologically, this deal teaches future power players that economic bullying can work. The lesson is clear: coercive leverage pays dividends. And the UK, a democratic power, just played along.

Realpolitik or Strategic Misstep?

Some may argue that Britain had little choice. Its economy is fragile, its post-Brexit trade agenda under strain, and its car and steel industries politically sensitive. In that light, a fast deal is better than prolonged pain. That may be true in the short term.

But long-term strategy requires thinking beyond immediate pain relief. Britain has surrendered leverage it might have used in a multilateral setting. It has lent legitimacy to an economic model built on unilateralism and transactional pressure. It has allowed itself to be framed not as an equal partner, but as the first domino.

This is not to say Starmer's government has no wins here. Jobs were saved. Market certainty has improved. But these come at a cost: emboldening a trade strategy rooted in coercion, and setting a precedent that others may now be pressured to follow.

Simply Put: A Precedent Set

Trump’s trade war is not over. Liberation Day was only the beginning. More tariffs are likely. More deals will follow. And when they do, negotiators in Brussels, Ottawa, and Tokyo will remember that Britain went first, and that going first meant going on Trump’s terms.

For the UK, this may prove to be a tactical win and a strategic error. In seeking immediate relief, it has helped normalise a worldview that rejects cooperation and celebrates power. And in doing so, it may have weakened the very international order it seeks to defend.

If Britain’s goal was global credibility, it may have traded it for short-term survival and in doing so, endorsed a world where the rules don’t matter, only the power to bend them.

References and Sources

Schelling, T. C. (1980).

The strategy of conflict. Harvard University Press.Trump hails framework of U.K. trade deal, but 10% tariffs will remain on some items - CBS News

Excerpt: Economic Sanctions and American Diplomacy | Council on Foreign Relations

Trump, Starmer herald limited US-UK trade deal, but 10% duties remain | Reuters

The Latest: UK says trade deal slashes tariffs on cars, steel and aluminum