Understanding the Body Schema and Its Relevance to Psychology

The human experience is deeply rooted in the awareness and perception of the body, which enables interaction with the world. Psychological and neuroscientific inquiries into this domain often explore two key constructs: the body schema and the body image. These concepts, while interrelated, represent distinct aspects of how we experience, use, and perceive our physical selves. Body schema refers to the dynamic, unconscious representation of the body's posture, movement, and spatial orientation. Conversely, body image is a conscious and often static reflection of the body's appearance, influenced by societal, emotional, and perceptual factors. Understanding body schema not only deepens our comprehension of motor control and spatial awareness but also sheds light on various psychological and clinical phenomena, including neurorehabilitation, identity, and disorders of self-perception.

Defining Body Schema

The body schema is a continuously updated sensorimotor representation of the body that integrates inputs from multiple sensory modalities, including vision, touch, proprioception, and vestibular signals. Unlike body image, which is conceptual and visual, body schema operates largely at an unconscious level and is instrumental in planning and executing movements. It allows individuals to navigate their environment, maintain balance, and adapt to changing conditions without requiring constant visual monitoring.

Renowned theorists such as de Vignemont and Gallagher emphasize the functional and automatic nature of the body schema. De Vignemont defines it as a real-time representation of posture that adapts dynamically to changes in body position, even in the absence of visual cues. Gallagher contrasts body schema with body image, framing the former as a system of sensorimotor skills that function without conscious oversight. Empirical studies validate this distinction, demonstrating that patients with disrupted body schema (e.g., due to deafferentation) struggle with movement control, while those with body image disturbances often experience perceptual or emotional issues.

Body Schema in Action

Body schema plays a central role in integrating motor and sensory functions to enable smooth and coordinated actions. For instance, tasks such as reaching for an object or navigating through a crowded room require constant updates to the body's spatial representation. This dynamic representation is evident in phenomena such as the rubber hand illusion, where individuals incorporate an artificial limb into their body schema after multisensory stimulation. Such flexibility underscores the plasticity of the body schema, which adapts to both temporary and permanent changes in the body.

The Intersection of Body Schema and Psychology

The study of body schema has significant implications for psychology, particularly in understanding identity, action, and disorders of self-perception. Below are some key areas where body schema is relevant:

Motor Control and Rehabilitation

Disorders such as stroke or traumatic brain injuries often impair motor functions and disrupt the body schema. Rehabilitation techniques like mirror therapy, graded motor imagery, and virtual reality-based interventions aim to restore the body schema by recalibrating the sensorimotor connections. For example, mirror therapy, which involves viewing the reflection of an intact limb, helps amputees manage phantom limb pain by reestablishing a coherent body schema. Similarly, virtual reality applications allow patients to "embody" virtual limbs, facilitating the recovery of motor functions.Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders

The disruption of body schema is evident in various conditions, including neglect syndrome, somatoparaphrenia, and eating disorders. Neglect syndrome, often resulting from right hemisphere damage, leads to the inability to attend to one side of the body or space, highlighting the role of body schema in spatial awareness. In somatoparaphrenia, individuals deny ownership of a limb, indicating a profound disconnection between the body schema and conscious awareness.In eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, body schema and body image interact in maladaptive ways, leading to distorted perceptions of body size and shape. Research suggests that therapeutic interventions targeting body schema, such as motor imagery and cognitive-behavioral therapy, may alleviate these distortions.

Identity and Embodiment

The body schema is intricately linked to one's sense of self. The co-construction model proposed by Pitron and colleagues suggests that body schema and body image influence each other through feedback loops. In this framework, body schema provides the foundation for body image, which in turn shapes one's social identity and self-perception. This relationship is particularly evident in disorders like body integrity identity disorder (BIID), where individuals experience a mismatch between their body schema and their idealized body image.Phantom Limbs and Neural Plasticity

Phantom limb sensations, experienced by amputees, underscore the persistence of body schema despite the physical absence of a limb. These sensations arise from cortical reorganization, where the brain attempts to integrate sensory feedback from the missing limb. Therapies such as virtual reality and motor imagery leverage this plasticity to modify the body schema and alleviate phantom limb pain.

Experimental Insights and Methodologies

The assessment of body schema involves experimental tasks that probe sensorimotor integration and spatial awareness. Techniques such as motor imagery, pointing tasks, and mental rotation of body parts have been used to investigate the integrity of the body schema in both healthy individuals and clinical populations. For example, in motor imagery tasks, participants imagine performing movements, revealing how body schema underpins action planning and execution.

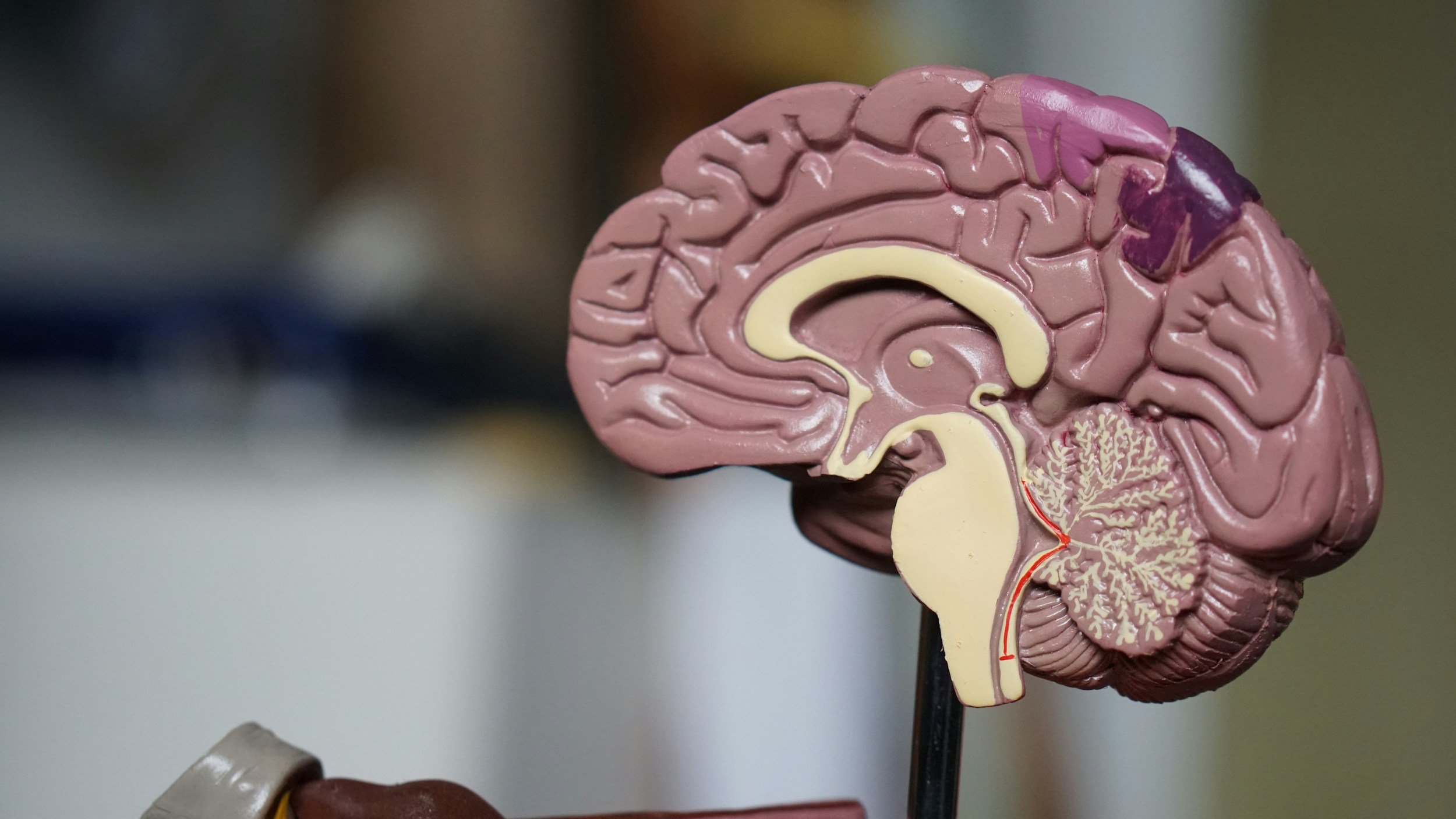

Advances in neuroimaging have also illuminated the neural substrates of body schema. Studies identify regions such as the extrastriate body area (EBA) and the fusiform body area (FBA) as critical for body perception. These areas, along with the right temporoparietal junction (TPJ) and primary motor and somatosensory cortices, form a network that supports body schema and its integration with external stimuli.

Applications in Prosthetics, Virtual Environments, and Human-Machine Interfaces

The dynamic and plastic nature of the body schema makes it a crucial concept in the design of technologies that extend or restore human capabilities. Innovations in prosthetics, virtual reality (VR), and human-machine interfaces (HMI) increasingly rely on an understanding of how the brain integrates external tools and environments into the body schema.

Prosthetic Design and Integration

Advanced prosthetics aim to become an extension of the user's body, seamlessly integrated into their body schema. Research on body schema adaptation has informed the development of prosthetic limbs that provide sensory feedback, such as tactile or proprioceptive signals. By mimicking the sensory and motor functions of natural limbs, these devices help users develop a sense of ownership over the prosthetic, reducing rejection rates and improving usability.

For example, neuroprosthetics use neural interfaces to directly connect prosthetic limbs to the nervous system, enabling precise motor control and sensory feedback. Techniques like graded motor imagery and virtual embodiment further facilitate this integration by helping users mentally and physically incorporate the prosthetic into their body schema.Virtual Reality and Embodiment

VR systems leverage the body schema to create immersive and interactive environments. Through first-person perspectives and multisensory feedback, VR can simulate the sensation of inhabiting a virtual body or avatar. This has applications in gaming, training, and therapy, where the ability to "embody" a virtual self enhances user engagement and learning outcomes.

VR's embodiment effects are also being explored for rehabilitation, such as helping stroke patients regain motor function. By embodying a virtual limb that mirrors intended movements, patients can "trick" their brain into perceiving successful motor actions, promoting neuroplasticity and recovery.Human-Machine Interfaces (HMI)

The integration of tools, devices, and interfaces into the body schema is critical for designing effective HMIs. Devices such as exoskeletons, robotic limbs, and even wearable technology must align with the brain's sensorimotor systems to ensure intuitive control. HMIs that fail to integrate with the body schema can cause discomfort or inefficiency, reducing their usability.

Research into body schema adaptation has led to interfaces that provide real-time feedback, allowing users to adjust their actions based on the device's performance. For instance, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) enable direct communication between the brain and external devices, allowing users to control robotic arms or cursors with their thoughts. These systems exploit the brain's ability to remap the body schema to incorporate external tools.Expanding the Boundaries of the Body Schema

Understanding the body schema's plasticity opens possibilities for enhancing human capabilities. Technologies that expand the sensory or motor capacities of the body—such as extending reach through robotic arms or enhancing vision with augmented reality—depend on the brain's ability to incorporate these extensions into its body schema.

For example, experimental studies show that users can adapt to controlling extra robotic limbs or even experience them as part of their body, as long as the sensory feedback and control mechanisms align with their natural movements. Such advancements could have transformative applications in industries requiring precision, such as surgery or manufacturing.

By understanding how the body schema integrates external elements, designers can create technologies that feel intuitive, enhance human abilities, and improve quality of life. This intersection of psychology, neuroscience, and technology offers profound insights into how we perceive and extend ourselves in an increasingly interconnected world.

Simply Put

The body schema is a foundational construct that bridges the physical and psychological aspects of human experience. Its role in motor control, spatial awareness, and self-perception makes it a critical area of study in psychology and neuroscience. By exploring the interplay between body schema and body image, researchers can better understand the mechanisms underlying identity, action, and disorders of self-representation. Moreover, innovative therapies targeting body schema hold promise for improving outcomes in neurological and psychiatric conditions, offering new avenues for rehabilitation and self-reintegration. In a world where technology increasingly mediates our interactions, understanding the body schema may also inform the design of prosthetics, virtual environments, and human-machine interfaces, enhancing our ability to adapt and thrive.

References

Gallagher, S. (2005). How the body shapes the mind. Oxford University Press.

Learn about action potential in psychology, a fundamental process in neural communication affecting perception, learning, memory, and behavior. Discover its phases, importance, and link to disorders.