The Stanford Prison Experiment: A Case Study in Social Influence and Ethical Controversy

A Brief Review

The Stanford Prison Experiment, also known as the Zimbardo Experiment, remains one of the most widely discussed and controversial studies in the field of social psychology. Conducted in 1971 by psychologist Philip Zimbardo at Stanford University, the study aimed to explore the power of situational factors and social roles in shaping human behaviour. Despite its significant impact on our understanding of social influence, the experiment has been heavily criticized for its ethical lapses and methodological flaws. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Stanford Prison Experiment, its findings, critiques, and its lasting legacy in the context of psychological research.

🔑 Key Points:

- The Stanford Prison Experiment (1971) examined the psychological effects of perceived power and role conformity in a simulated prison setting.

- The study was halted after 6 days due to extreme psychological distress and escalating abusive behavior by "guards."

- It revealed how situational forces and assigned roles can override personal identity and ethical judgment.

- The study has been widely criticized for ethical violations, demand characteristics, and methodological flaws.

- It led to significant reforms in psychological research ethics, including IRB requirements and stricter informed consent procedures.

Background and Objectives

Zimbardo and his team sought to investigate how individuals conform to social roles, particularly in environments with stark power differentials, such as prisons. Inspired by questions surrounding the behaviour of prison guards and inmates, particularly in the wake of abuses in American and international correctional facilities, the experiment aimed to isolate situational causes of aggressive and submissive behaviour, rather than attributing such actions solely to personality traits.

Design and Methodology

Twenty-four male college students were selected from a larger pool of over 70 volunteers. Participants were carefully screened to ensure psychological stability, absence of criminal backgrounds, and no history of drug abuse or mental illness. While the selection process attempted to eliminate significant personality differences, later critiques questioned whether the very nature of the study attracted individuals with authoritarian or aggressive predispositions.

Participants were randomly assigned to the role of either "guard" or "prisoner". A mock prison was constructed in the basement of the Stanford psychology building. The simulation was designed to replicate a realistic prison environment, complete with cells, uniforms, identification numbers for prisoners, and standard-issue sunglasses for guards to reduce eye contact and humanization.

The experiment was scheduled to last two weeks. However, it was abruptly terminated after only six days due to the extreme and disturbing behaviours that emerged, and the psychological toll on participants.

Findings: A Descent into Role Conformity

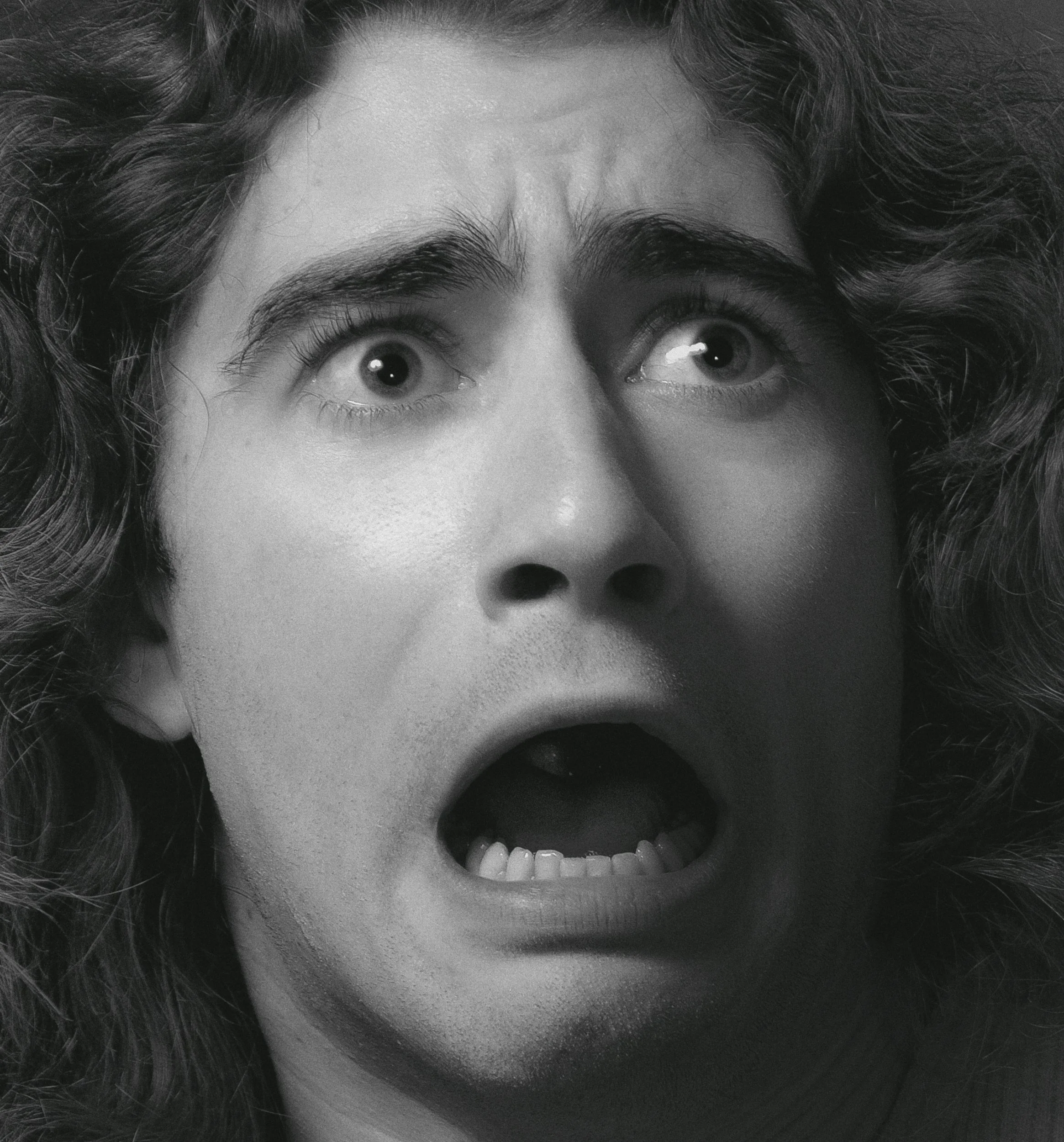

The results of the Stanford Prison Experiment seemed to confirm Zimbardo's hypothesis about the influence of social roles and environments. Guards began to exhibit authoritarian and, in some cases, sadistic behaviour towards the prisoners. Many prisoners became passive, anxious, and showed signs of severe emotional distress.

One particularly alarming incident involved a prisoner suffering a psychological breakdown after just 36 hours. Other prisoners rebelled, went on hunger strikes, or became withdrawn. Guards implemented increasingly harsh tactics to control and dehumanize the prisoners, including psychological abuse, arbitrary punishments, and solitary confinement in a small, dark closet.

Zimbardo himself took on the role of prison superintendent, a decision that later drew significant ethical criticism. His involvement and lack of intervention arguably encouraged the continuation of harmful behaviours.

The study appeared to demonstrate the profound impact of social influence—how people conform to the expectations of their assigned roles within a given context. Ordinary individuals, placed in a setting with uneven power dynamics and vague moral guidance, behaved in ways they likely would not have outside of that environment.

Ethical and Methodological Critiques

Despite its initial acclaim, the Stanford Prison Experiment has since faced intense scrutiny. Critics have raised serious concerns regarding its ethics, scientific validity, and the conclusions drawn from its findings.

Informed Consent and Right to Withdraw: While participants signed consent forms, they were not fully informed of the potential for extreme psychological stress. Although they were told they could leave at any time, some were reportedly discouraged from doing so, and the procedures for withdrawal were not clearly upheld.

Psychological Harm: Several participants experienced lasting emotional distress, including nightmares, anxiety, and depression. One former prisoner described feeling extreme shame and disorientation after the experiment. The lack of adequate post-experiment debriefing and follow-up support exacerbated these effects.

Experimenter Bias: Zimbardo’s dual role as lead researcher and prison superintendent created a clear conflict of interest. His involvement may have inadvertently influenced the behaviour of guards and prevented earlier termination of the study.

Demand Characteristics: Some researchers argue that participants acted in ways they believed were expected of them. In interviews conducted years later, at least one guard admitted to modelling his behaviour on movie stereotypes. This raises questions about whether the behaviours observed were truly a result of the prison environment or simply performance based on perceived expectations.

Ecological Validity: The mock prison environment, while immersive, lacked many features of real correctional institutions. The guards received no training, and the structure was highly artificial. As a result, generalizing the findings to actual prison systems is problematic.

Sample Limitations: The participant pool consisted entirely of young, white, middle-class male college students, predominantly from Stanford University. This homogeneity limits the applicability of the findings to broader and more diverse populations.

Selection Bias: A 2007 study by Carnahan and McFarland found that individuals who volunteered for a "prison life" study scored higher on measures of aggressiveness and authoritarianism, suggesting that the initial pool of participants may have been predisposed to certain behaviours, skewing the results.

Re-evaluations and Replications

The Stanford Prison Experiment has inspired numerous discussions, documentaries, and reinterpretations. One notable attempt to revisit the findings was the BBC Prison Study conducted by social psychologists Alex Haslam and Stephen Reicher in 2002. Their study introduced similar conditions but emphasized ethical safeguards and transparency. Interestingly, the results did not mirror those of the Stanford experiment. Guards were reluctant to assert authority, and prisoners began to organize collectively, highlighting the role of group identity and agency rather than inevitable submission to roles.

These differing outcomes suggest that social influence is not an automatic process but one that interacts with individual values, leadership, context, and group dynamics. This challenges the deterministic view that situational roles alone are sufficient to elicit extreme behaviour.

Legacy and Impact

The Zimbardo Experiment remains a cornerstone in discussions about social influence and psychological ethics. It powerfully illustrates how context and systemic structures can shape behaviour. However, its scientific credibility is increasingly questioned. Many psychologists today regard the study more as a cautionary tale about research design and ethics than as definitive evidence of human nature.

Importantly, the ethical controversy surrounding the experiment contributed to the establishment of more rigorous ethical standards in psychological research. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), stricter informed consent procedures, and greater attention to participant welfare are all legacies of the SPE’s fallout.

Zimbardo has defended the study as a vital look into the dark side of human behaviour, though he has acknowledged its shortcomings. In later years, he turned his attention to research on heroism, promoting ways individuals can resist negative social pressures and act ethically under difficult circumstances.

Simply Put

The Stanford Prison Experiment remains a pivotal case study in understanding social influence, group behaviour, and the power of assigned roles. It also stands as a powerful reminder of the ethical responsibilities researchers bear when designing and conducting experiments involving human subjects. While the findings continue to spark debate, the experiment has undoubtedly shaped the landscape of modern psychology and ethics.

Ultimately, the Zimbardo Experiment serves both as an exploration into the capacity for cruelty within structured systems and a mirror reflecting the need for ethical vigilance in scientific inquiry. Its legacy endures—not just as a story of social psychology, but as a warning about the seductive power of authority, the malleability of identity, and the imperative to protect human dignity in all research endeavors.

📌 Frequently Asked Questions

🧠 Quick Quiz: Test Your Knowledge

References:

Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). On the ethics of intervention in human psychological research: With special reference to the Stanford Prison Experiment. Cognition, 2(2), 243-256.

Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International Journal of Criminology and Penology, 1, 69-97.

Zimbardo, P. G. (2007). The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. Random House.

Blum, B. (2018). The lifespan of a lie. Medium.