Social Identity Theory: Understanding the Psychology of Group Dynamics

Social Identity Theory (SIT) is one of the most influential frameworks in social psychology, offering a nuanced explanation of intergroup behaviour, prejudice, and group membership. Developed by Henri Tajfel and John Turner in the 1970s and 1980s, SIT explores how individuals derive part of their self-concept from their perceived membership in social groups. This theory has profound implications for understanding social behaviour, ranging from everyday group affiliations to large-scale conflicts.

This essay will explore the foundational principles of Social Identity Theory, the psychological processes underpinning it, its applications, and contemporary developments. It will also address criticisms and extensions of the theory to provide a comprehensive overview.

The Origins and Core Concepts of Social Identity Theory

Henri Tajfel, a Holocaust survivor, was deeply interested in understanding the roots of prejudice and discrimination. His early experiments in the 1970s laid the groundwork for SIT. The most famous of these, the "minimal group paradigm," demonstrated that even arbitrary group distinctions (e.g., being assigned to a group based on preference for a painting) could lead to in-group favouritism and out-group discrimination.

At the heart of SIT are three key psychological processes:

Social Categorisation: Individuals classify themselves and others into categories such as ethnicity, gender, nationality, or occupation. This process simplifies the social world and helps in structuring interactions.

Social Identification: People adopt the identity of the group they have categorized themselves as belonging to. This internalisation affects behaviour, emotions, and self-esteem.

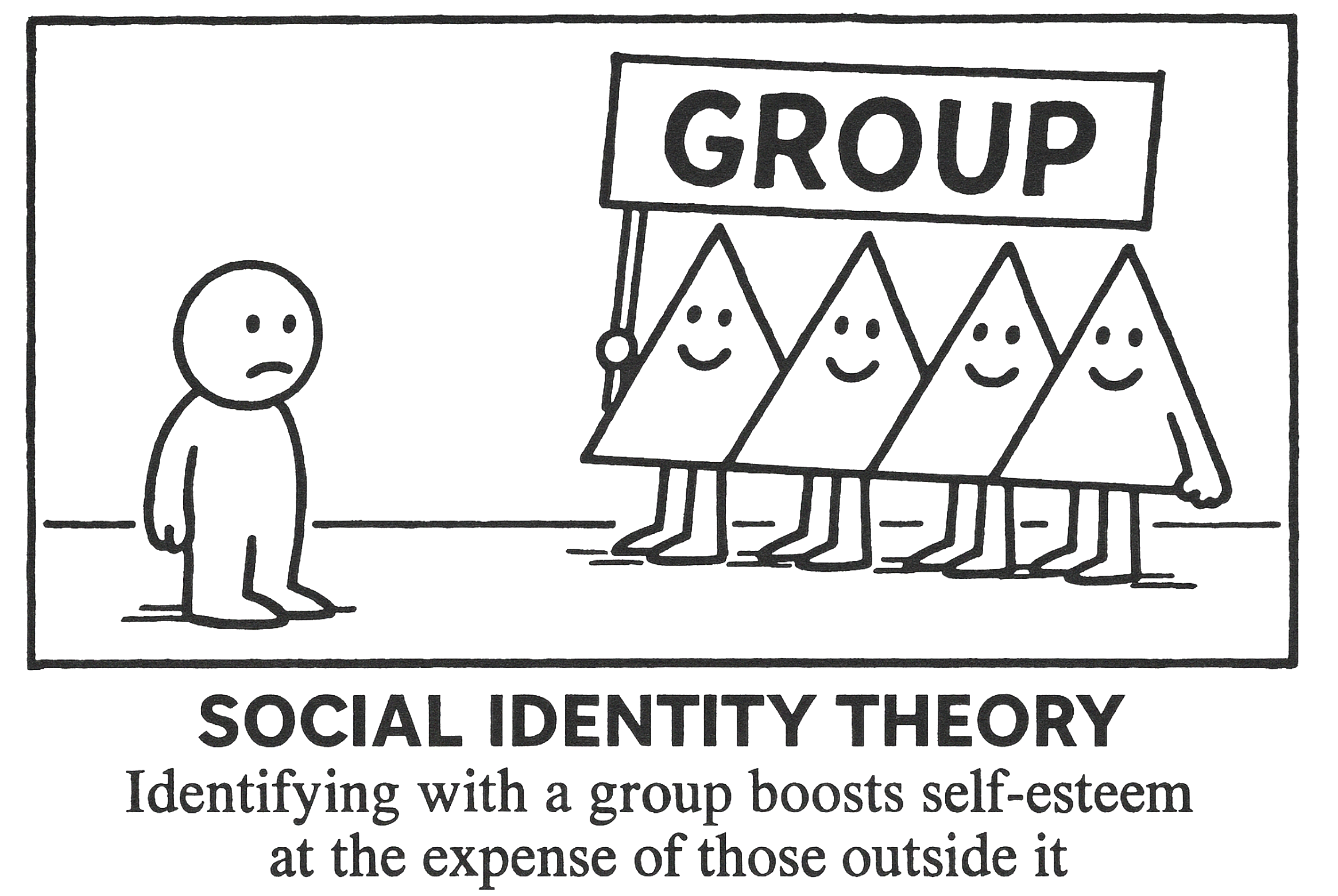

Social Comparison: Individuals compare their in-group with relevant out-groups. To maintain or enhance self-esteem, individuals tend to favour their own group over others, sometimes leading to prejudice or intergroup conflict.

These processes form a cyclical system where social identities reinforce group norms and behaviours, which in turn strengthen identification and differentiation.

Applications of Social Identity Theory

SIT has been applied extensively in various domains:

Prejudice and Discrimination: SIT explains how group biases arise not necessarily from personal animosity but from the psychological need to enhance group status. This insight has been used to address racial, ethnic, and nationalistic prejudices.

Organisational Behaviour: In workplace settings, employees may identify with their department or team, which affects cooperation, motivation, and competition. Understanding these dynamics helps in conflict resolution and organisational change.

Politics and Nationalism: Political identities are powerful social identities. SIT sheds light on how populist leaders exploit in-group/out-group narratives to mobilise support and marginalise dissent.

Education and Social Cohesion: Schools are microcosms of wider society where group identities can form around class, ability, or ethnicity. Interventions grounded in SIT promote inclusivity by fostering superordinate identities that transcend sub-group divisions.

Social Media and Online Communities: The rise of digital platforms has created new arenas for social identity formation. Online groups reinforce group norms and can contribute to polarisation or solidarity.

Critiques and Limitations of Social Identity Theory

While SIT is a robust framework, it has not been without criticism:

Reductionism: Some argue that SIT overemphasises cognitive processes and underplays the role of socio-economic and historical contexts in shaping group behaviour.

Insufficient Attention to Power Dynamics: Critics from critical and feminist perspectives note that SIT does not adequately account for systemic inequalities and the role of power in intergroup relations.

Static Group Boundaries: Early formulations of SIT tended to view group boundaries as fixed. In reality, identities are fluid, overlapping, and context-dependent.

To address these issues, scholars have developed extensions such as Self-Categorisation Theory (Turner et al., 1987), which delves deeper into how individuals shift between personal and social identities depending on context.

Recent Developments and Integrations

Contemporary research has expanded and refined SIT:

Intersectionality: Integrating SIT with intersectional theory helps account for how multiple social identities (e.g., race, gender, class) interact to shape experiences.

Dynamic Identity Theories: Modern approaches emphasise the fluidity of identity and how social identities can shift across contexts, especially in globalised and multicultural societies.

Neuroscientific Insights: Emerging research in social neuroscience explores the brain regions involved in in-group and out-group processing, providing biological underpinnings to SIT’s psychological mechanisms.

Intergroup Contact Theory: While distinct, this theory complements SIT by suggesting that under certain conditions, contact between groups can reduce prejudice. SIT helps explain why such interventions sometimes fail—if the in-group identity is threatened, contact may exacerbate divisions.

Climate Change and Collective Action: Social identity is increasingly recognised as pivotal in mobilising collective action for global issues. Identifying with environmentalist or activist groups can drive behaviour change.

Simply Put

Social Identity Theory remains a cornerstone of social psychology, offering critical insights into how and why group affiliations shape human thought, emotion, and behaviour. Its relevance spans a vast array of domains, from intergroup conflict and discrimination to organisational dynamics and digital communities. While it has its limitations, ongoing refinements and interdisciplinary integrations continue to enhance its explanatory power.

Understanding SIT is not merely an academic exercise—it has real-world implications. As societies become more diverse and interconnected, fostering inclusive social identities may be key to addressing some of the most pressing challenges of our time.