Criticism of the Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger Effect (DKE), a cognitive bias where people with low ability in a domain overestimate their competence, has gained significant attention since its conceptualization in 1999 by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger. The catchy premise, that those who know the least about a subject are often the most confident in their knowledge, has made it a favourite topic in popular psychology and internet culture. However, as the concept has become increasingly popular, it has also faced scrutiny and criticism from academics and practitioners. This article examines the scientific criticisms of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, its methodological challenges, theoretical debates, and the implications of its widespread misinterpretation.

What is the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

Dunning and Kruger’s seminal study, published in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, investigated the relationship between self-assessed competence and actual performance. They found that individuals with the least expertise in areas such as grammar, logical reasoning, and humor were the most likely to overestimate their abilities. The underlying explanation was twofold:

Metacognitive Deficits: Individuals who lack skill in a particular domain also lack the ability to accurately assess their performance.

Illusory Superiority: People with low competence are more likely to rate themselves above average because they cannot recognize their shortcomings.

This phenomenon was graphically represented as a U-shaped curve showing the discrepancy between perceived and actual performance, with the least skilled overestimating themselves and the most skilled slightly underestimating their abilities.

Methodological Concerns

One of the primary criticisms of the Dunning-Kruger Effect lies in the methodology of the original study and subsequent replications.

Statistical Artefacts

Several critics argue that the Dunning-Kruger Effect might arise as a statistical artefact rather than a genuine psychological phenomenon. Regression to the mean, a common statistical principle, suggests that extreme scores (low or high) on any measure tend to be closer to the average on subsequent measures. This could explain why low performers appear to overestimate their abilities and high performers underestimate theirs. Studies have suggested that the observed effect may not necessarily reflect cognitive bias but could simply result from statistical noise.

Measurement and Scaling Issues

Critics have highlighted issues with how self-assessed competence is measured. Most studies rely on self-report scales, which are prone to biases such as social desirability and cultural differences in self-perception. Additionally, the DKE assumes a linear relationship between self-perceived competence and actual performance, which might oversimplify the complexity of self-assessment.

Lack of Domain-General Validity

While the DKE has been observed in specific domains, some researchers argue that it is not a universal phenomenon. In highly technical or knowledge-intensive areas, individuals may be less prone to overestimating their abilities because the gap between lay knowledge and expertise is more apparent. This variability calls into question the generalizability of the effect.

Oversimplification of Metacognition

The Dunning-Kruger Effect hinges on the idea that metacognitive deficits prevent low performers from recognizing their incompetence. However, metacognition is a complex and multidimensional construct. Critics argue that Dunning and Kruger’s framework oversimplifies this cognitive process.

Overemphasis on Incompetence

The model assumes that low performers are unaware of their lack of skill, but research shows that individuals often have some awareness of their limitations, particularly after receiving feedback or gaining more experience. Furthermore, the effect does not adequately consider external factors like anxiety, imposter syndrome, or situational pressures that might influence self-assessments.

Neglect of Contextual Factors

Competence is context-dependent, and the accuracy of self-assessment may vary based on the environment, the complexity of the task, or the level of expertise required. By focusing primarily on individual cognitive deficits, the DKE neglects social and environmental influences on perceived competence.

Popular Misinterpretation

The widespread popularity of the Dunning-Kruger Effect has led to several misconceptions and misuses in both academic and non-academic contexts.

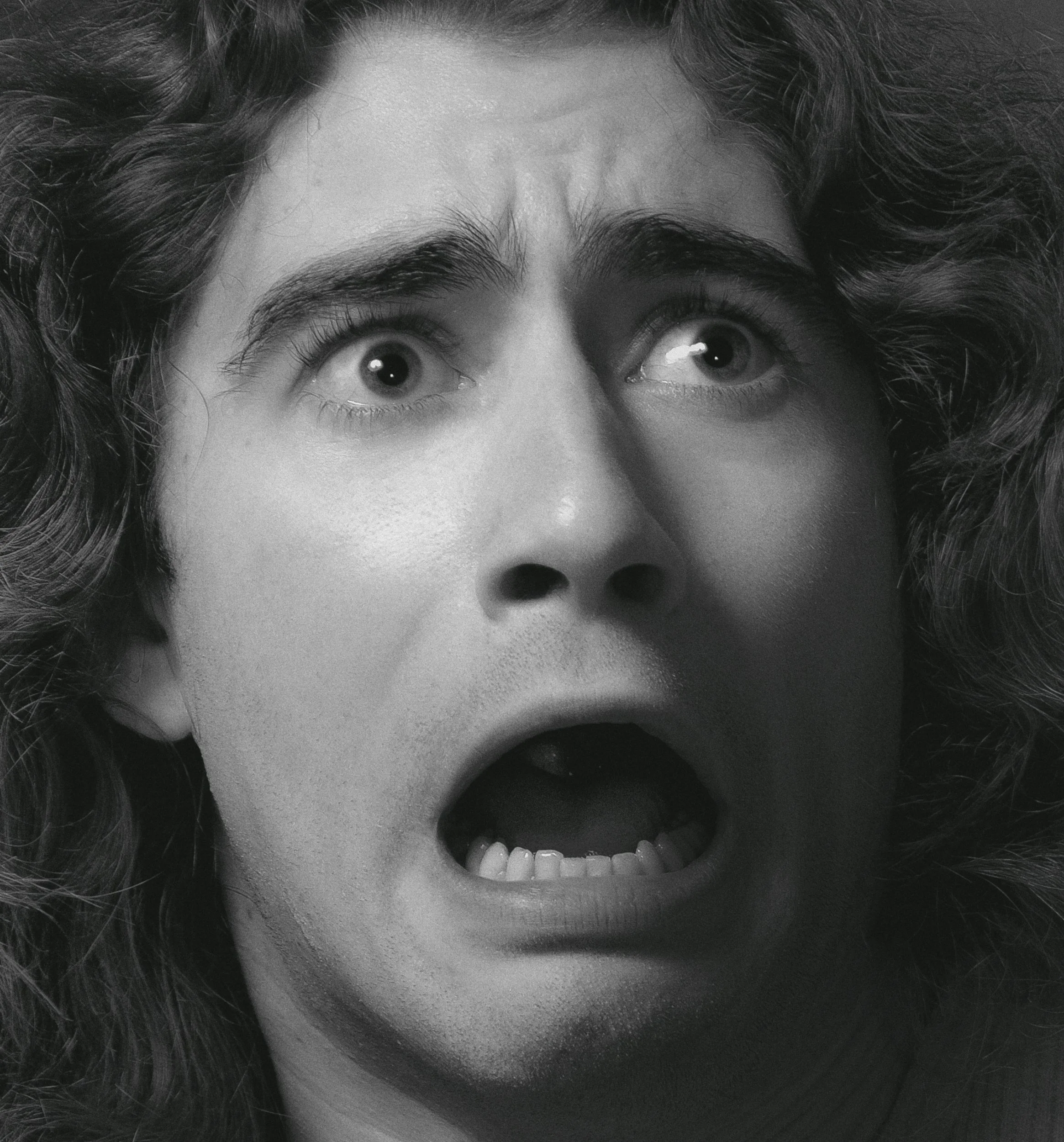

Meme Culture and Overgeneralization

Internet memes often portray the DKE as a universal truth about ignorance, frequently reducing it to a simplistic "stupid people are too stupid to know they are stupid" narrative. This reductive interpretation strips the concept of its scientific nuance and fosters an elitist attitude toward those who overestimate their abilities.

Misapplication in Policy and Practice

The DKE is sometimes invoked to explain phenomena like vaccine hesitancy, political polarization, or misinformation. While there may be some correlation, attributing these behaviors solely to the Dunning-Kruger Effect risks ignoring broader sociocultural, psychological, and economic factors.

Overlap with Other Biases

Critics have noted that the DKE overlaps with other well-documented biases, such as the better-than-average effect, overconfidence bias, and optimism bias. This overlap raises questions about whether the DKE is a distinct phenomenon or merely a subset of broader cognitive biases.

Lack of Longitudinal Evidence

Much of the research on the Dunning-Kruger Effect is cross-sectional, measuring self-assessment and performance at a single point in time. Critics argue that this approach fails to capture the dynamic nature of learning and self-awareness. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether low performers become more accurate in their self-assessments over time as they gain experience or receive feedback.

Responses to Criticism

Proponents of the Dunning-Kruger Effect have addressed some of these criticisms. For example, David Dunning has acknowledged the role of statistical artefacts but argues that the underlying phenomenon; a gap between perceived and actual competence remains robust. Recent studies have also explored ways to improve measurement techniques, such as using more objective performance metrics and incorporating longitudinal designs.

Simply Put

The Dunning-Kruger Effect has undoubtedly enriched our understanding of human cognition and self-perception, but it is not without its flaws. Critics have highlighted methodological limitations, theoretical oversimplifications, and the risks of popular misinterpretation. Rather than dismissing the effect outright, these criticisms should encourage researchers to refine their methods and broaden their theoretical frameworks.

Ultimately, the Dunning-Kruger Effect serves as a reminder of the complexity of human cognition. It underscores the importance of humility, not only for those prone to overestimating their abilities but also for researchers and practitioners seeking to unravel the intricacies of the human mind. By approaching the DKE with a critical yet open-minded perspective, we can deepen our understanding of competence, confidence, and the fascinating connections between them.

References

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.